A key Alzheimer’s gene has been implicated in a second, distinctive brain disorder, revealing a dual threat to cognitive health.

The APOE4 gene, a well-known genetic risk factor for Alzheimer’s disease, has now been identified as an independent risk factor for delirium.

For each copy of the APOE4 gene a person carried, their risk of delirium increased by approximately 60 percent.

This means someone with one copy had 1.6 times the risk, while someone with two copies faced a substantially higher risk, between 2.6 and three times that of someone with no APOE4 copies.

The new study from the UK shows that delirium is more than just a side effect of existing dementia. It can be a major early warning sign that can actively speed up future mental decline, even in people who seem cognitively healthy.

Typically triggered by a severe infection or surgery, delirium causes sudden confusion and disorientation.

The inflammation from these events damages brain cells, which is the same process that drives dementia, creating a dangerous biological bridge between the two conditions.

The APOE4 gene makes the brain uniquely susceptible to these inflammatory assaults, a discovery that opens the door to targeted treatments that can intercept this process and prevent delirium from triggering permanent cognitive decline.

The APOE4 gene, a major risk factor for Alzheimer’s, is now also confirmed as an independent risk factor for delirium. This means even adults without dementia are far more vulnerable to delirium if they carry this gene (stock)

This dangerous feedback loop means that a single episode of delirium can permanently alter a patient’s cognitive trajectory.

The acute brain inflammation from delirium not only causes temporary confusion. It actively fuels the same pathological processes that cause long-term neurodegenerative damage.

To determine the link between the Alzheimer’s gene and delirium, researchers combined health and genetic data from over a million people across several large international biobanks, including the UK Biobank.

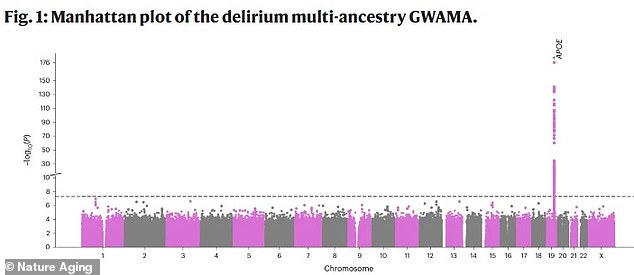

Using this vast dataset, they scanned millions of points in human DNA to identify specific genetic variants associated with a higher risk of delirium.

The team also analyzed blood samples from over 30,000 people, examining nearly 3,000 proteins years before any of them experienced delirium.

Using advanced machine learning and statistical techniques, they identified which proteins could predict future delirium risk and investigated whether future drugs could target them.

This risk of experiencing delirium is not just a byproduct of the gene’s link to dementia.

Instead, APOE4 appears to directly weaken the brain’s defenses, making it more susceptible to the inflammatory assaults like pneumonia that trigger delirium.

This graph shows the results of a genome-wide search for genes linked to delirium. Each point represents a single DNA change. The x-axis shows its location in the genome, while the y-axis shows the statistical significance of that link. The most significant finding was a spike on chromosome 19, annotated as the APOE gene, identifying it as the strongest genetic risk factor for delirium

Delirium often manifests as a sudden and noticeable shift in a person’s mental state and abilities. A person with delirium may become confused, disoriented, and have severe difficulty focusing or following a conversation.

Their personality can change, making them withdrawn, agitated and suspicious, and they may say things that don’t make sense or experience hallucinations.

They may struggle to make sense, say illogical things or even experience hallucinations.

A key sign is a marked decline in their ability to perform routine, everyday activities.

Delirium poses a massive challenge in healthcare for the elderly.

It strikes up to half of all seniors in the hospital, a number that soars to more than 70 percent for those in the ICU and affects a significant portion, up to 60 percent of people in nursing homes.

Vasilis Raptis, the main author of the study from the University of Edinburgh, said: ‘The study provides the strongest evidence to date that delirium has a genetic component.

‘Our next step is to understand how DNA modifications and changes in gene expression in brain cells can lead to delirium.’

A separate, advanced analysis confirmed that a specific region on the 19th chromosome, home to the APOE gene, plays a central role in delirium.

It highlighted four specific genes in that area, APOE, TOMM40, PVRL2 and BCAM, as being critically involved in the disease process, solidifying this region as a prime focus for future research and therapeutic intervention.

Australian actor Chris Hemsworth took a hiatus in 2022 after learning that he had inherited two copies of APOE4, dubbed ‘the Alzheimer’s gene’, from his parents. Studies show that having both copies increases the risk by 10 to 15 times. Having one copy can double a person’s risk

A brain affected by dementia is already in a fragile state, weakened by the cumulative damage of the disease.

Its neural networks are compromised and the brain has less backup capacity to cope with any new stressors.

When a major stressor, like an infection or surgery, occurs, the body’s immune system launches an aggressive assault that further damages the blood-brain barrier, stresses brain cells and can be directly toxic to neurons.

While delirium lasts between hours and a day or two, it causes lasting physical harm by destroying critical neural connections and actively accelerating the very disease processes the brain was already fighting, leading to further rapid decline.

The UK team’s results were published in the journal Nature Aging.