Guilt can be good. It is healthy when it alerts us to having wronged someone and prompts us to put things right by apologising and repairing any damage we’ve done. But false guilt is not – the ridiculous sort our society is currently indulging in about slavery and Britain’s colonial past.

As reparations running into trillions of pounds are demanded for the part Britons played in the slave trade centuries ago, this imaginary guilt is a canker and a tyranny that is misshaping the policies of our governments and cultural institutions.

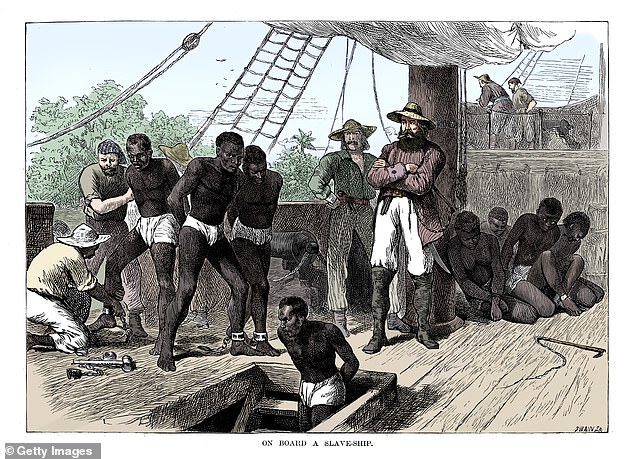

There is no denying that, from about 1650 to the early 1800s, British people were involved in transporting African slaves across the Atlantic. The conditions were horrific, the human cargo tightly packed below decks, shackled, starved of fresh air and sunlight, malnourished, dehydrated and prey to disease for a voyage lasting up to six weeks.

One African who survived described ‘the stench of the hold; the filth of the tubs [latrine buckets] into which the children often fell; the shrieks of the women, the groans of the dying’. Nearly a quarter could be ‘lost in transit’.

And once they arrived in the Caribbean or the American colonies, they were sold at auction as chattels, often separated from their families, then put to back-breaking, soul-destroying work in gangs on sugar, tobacco or rice plantations where some were whipped till they bled, castrated, even burned alive.

This was a reprehensible moment in our history.

But it was the British Parliament that led the way in 1833 by abolishing slavery and soon after banning it throughout the British Empire.

Yet more than 200 years later, Britain’s role in spearheading the abolition of slavery is ignored and reparations are being demanded from us for the original sin.

Calls have been growing in recent years for Britain to pay reparations for its role in the trans-Atlantic slave trade

From about 1650 to the early 1800s, British people were involved in transporting African slaves across the Atlantic

The demands began in 2013 when the 20 states that make up Caricom, the organisation that represents Caribbean nations, established a commission to press for payback from Britain and other former European colonial rulers for historic ‘genocide and slavery’.

The outspoken chairman of the commission, Barbados-born academic Sir Hilary Beckles, told the House of Commons that 250 years of slave trading and chattel slavery followed by 100 years of colonial oppression were the result of ‘attitudes that were clearly genocidal’.

The British state, he added, forcefully extracted wealth from the Caribbean, resulting in its persistent, endemic poverty. A report later calculated, with apparent financial precision, the debt owed by Britain as just short of a staggering £20trillion.

Only this month, the stakes were raised when African nations made their own demands for reparations from former colonial powers for exploiting the continent’s people, land and resources in the 19th Century. And this week, publicising his forthcoming book on the case for slavery reparations, the actor Lenny Henry talked of ‘hundreds of years of being oppressed and downtrodden’ and a cost of ‘trillions and trillions of pounds’.

But, as an academic – I am a former regius professor at Oxford, a theologian and an ordained Anglican priest – I contend that the case for reparations for historic slavery does not stack up.

It is based on assumptions that are wildly distorted and not only historical nonsense but cartoonish in their simplicity, as the champions of reparations peddle their narrative of moral indignation, summarily condemning anyone who had anything to do with slavery as simply evil.

Such a fiercely absolute moral judgment lacks any historical awareness. They like to argue that Britain’s behaviour was uniquely abhorrent, such a heinous crime against humanity that the British, having perpetrated it, can claim no credit at all for actually stopping it.

Unique? I don’t think so. Slavery was a universal institution that existed from the dawn of time, though advocates for reparations choose to downplay this context. Across the globe societies employed slave labour in agriculture, mining, public works and even as troops.

Keir Starmer and former Deputy PM Angela Rayner taking the knee in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement – which supports reparations

Trinidadian historian (and, later, prime minister) Eric Williams, has argued that Britain owes reparations because slavery allowed it to develop more than other nations

In the third millennium BC – 5,000 years ago – all the ancient Mesopotamian civilisations practised it in one form or another, starting with Egypt. Around the shores of the Mediterranean Sea, the ancient Greeks, Carthaginians and Romans followed their example. To the east, slavery could be found among the Chinese from at least the seventh century AD and subsequently among the Japanese and Koreans. In the 1440s, the Portuguese were the first to seek slaves from West Africa, to make up for a labour shortage at home.

Africans were busy enslaving other Africans and selling them to the Romans and Arabs centuries before British merchant ships first appeared off that same coast in the mid-1600s.

Across the Atlantic, the Incas and the Aztecs extracted forced labour from subject peoples and the Comanches built a slave economy in what is now the south-west of the United States.

In the Islamic world, slavery was sanctioned by the Prophet Mohammed and legitimated by the Koran and holy law. The Vikings supplied markets in Arab Spain and Egypt with slaves – white slaves – from eastern Europe and the British Isles. Pirates from the Barbary Coast of North Africa raided English merchant ships and even villages in Cornwall and west Cork for slaves.

One estimate is that raiders from Tunis, Algiers and Tripoli alone enslaved more than a million Europeans between the beginning of the 16th Century and the middle of the 18th Century. The Muslim slave trade as a whole, which endured for 15 centuries, until 1920, transported about 17 million slaves, mostly African, exceeding by a considerable margin the approximately 11 million shipped by Europeans across the Atlantic. Hereditary slavery even continues today in Mali and Mauritania.

But the current discussion about reparations still insists that the British enslavement of blacks was something extraordinary and blames it for the white-versus-black racism that infects British and other anglophone societies today.

The humiliation and cruelty of British slave-trading and slavery was unique neither in kind nor degree. Many, many other peoples did similarly lamentable things, not least Africans and Arabs, and for a much longer period of time. The racially discriminatory fingering of the British is unfair and politically opportunistic.

To acknowledge this long and universal history of slavery is not to condone it. There are good reasons to regard enslavement as morally wrong in principle. But some moral truths that are obvious to us were just not obvious to our ancestors. To us, there is no doubting that slavery is wrong, because it makes one person the disposable property of another.

At the height of the Black Lives Matter movement, protesters in Bristol sent a statue of Edward Colston – a prolific slave trader – into the estuary

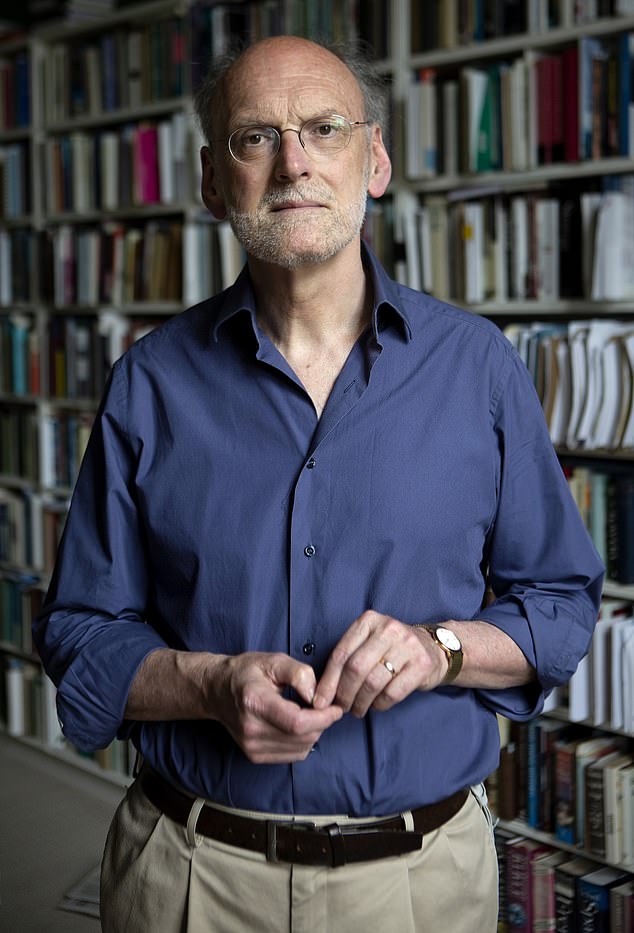

Nigel Biggar argues the debate around reparations is much more complex and Britain’s role in ending the slave trade is often overlooked

But to most of our ancestors slavery was a fact of life. There could be good or bad forms of it – some granted slaves certain rights, others not; some were merciful, others cruel – but the institution itself was taken for granted.

It’s all too easy to condemn past generations for this. But if we suspend judgment for a moment and examine the circumstances in which our ancestors had to operate, this may give rise to a modicum of sympathy.

Then, when we judge them, our judgment will be humbled, less puffed up with self-righteous indignation, because we are aware that, had we suffered those same circumstances, we might well have done likewise. No doubt, we will still judge slavery to be immoral, but without the self-inflating bombast and rigid self-righteousness that seems to infect so much of this debate.

Regardless, those arguing for reparations insist on ignoring the historical context in their rush to judgment. Moreover, they argue that Britain does indeed bear a singular responsibility because the profits from a century and a half of slave-trading and slavery financed the industrial revolution that gave the UK a head start in the world – an argument put forward forcibly back in 1944 by Trinidadian historian (and, later, prime minister) Eric Williams.

There is no doubt that the slave trade profited some Britons directly and many others indirectly. But how much it actually contributed to the country’s overall wealth is uncertain.

Almost no economic historian agrees with Williams that it made an ‘enormous’ contribution to Britain’s industrial development and that Britain’s industrial prosperity was ‘founded’ on it. Economic historian David Richardson estimates that profits from the slave trade added no more than 1 per cent of total domestic investment around 1790. It’s likely too that only 1.5 per cent of British ships were ever involved in the trade, the profits from which could have made very little contribution to industrialisation.

The same goes for the argument that the Atlantic slave-based economy – especially sugar production – made a decisive contribution to Britain’s industrial development. Its role as an engine of economic growth was marginal compared with other industries such as textiles, coal, iron ore and agriculture.

I do accept that slavery generated profits for some individuals and that these profits were invested in technological advances whose benefits have trickled down the centuries – as a result of which more of Britain’s present prosperity is ‘tainted’ by slavery than meets the eye. But so too is it by the unjust exploitation of nameless medieval serfs and Victorian industrial workers.

The truth is that little of what anyone, anywhere inherits is untainted by some historic wrongdoing or other. We cannot scrub out the stain; all we can do is strive to be better.

As for the effects of colonial slavery on Africa, from where most of the slaves were originally taken, some hold that it had devastating consequences, causing widespread depopulation and economic dislocation, undermining the fabric of African societies. This is probably true in that British demand for slaves stimulated African endeavours to supply them – and thereby provoking an increase in war and slave-raiding.

But while British investors and merchants bear responsibility for that, so do their African suppliers who made large profits from helping to meet the demand for slaves, capturing them in wars and raids, even taking them in lieu of debt.

African rulers actively resisted Britain’s insistence on abolition. So, if reparations are to be paid, then Africans themselves might rightly be asked to pay up.

Anti-slavery sentiment led to the founding of the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade in London in 1787. In 1791 about 30 per cent of the adult male population of Britain signed anti-slavery petitions.

What, then, does the case for reparations amount to? Not a lot in my considered opinion. Given that the jungle of history overgrows and obscures causal pathways, can we even say with certainty who should shoulder the blame? The victims of historic British slavery are, of course, all long dead and lie forever beyond the reach of restitution or compensation.

As for their 21st-Century descendants, their present condition, while perhaps owing something to the enslavement of their ancestors, also owes much more to events and choices in the almost 200 years since emancipation.

Take the claim that the legacy of slavery wrecked those Caribbean states where it had been practised and that Britain deliberately undermined their economies when they became independent, for which they should now be compensated. But the facts tell a different story.

Some islands did well because they were well governed – Barbados for example – while others, such as Jamaica, languished because their economies were badly managed.

It is also argued that the living descendants of enslaved Africans in the Caribbean continue to suffer ‘intergenerational trauma’ – that the experience of enslavement suffered by their ancestors has impressed itself deeply on subsequent generations so that the psychological and social damage done in the 1700s and early 1800s still reverberates today.

But there is nobody on earth whose ancestors did not suffer grievous injuries of some sort or other. And surely as time passes, and one generation succeeds another, the trace weakens, the scars become less inflamed, the effects attenuate. Besides, if the intention is to right grave historic wrongs, why should slavery be the sole focus? The plight of medieval serfs or early industrial workers toiling in factories and mines and dwelling in urban slums may have been better than that of slaves toiling in the West Indies, but not by much.

The list of all those who suffered at the hands of brutal masters in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries is long and includes women, children, industrial workers, religious minorities, soldiers and sailors. Out of all the eligible candidates for reparations for ancient sins, how can we justify selecting black slaves for special consideration?

It does not necessarily follow that we must deploy our inheritance to unravel history and reverse the centuries-old wrongdoing that helped to produce it. We did not do the wrong. Those wronged are all dead. And between then and now, much else may have intervened to enable their descendants to transcend the effects.

Moreover, why should British slavery be the focus? If the historic injustice of slavery is to be rectified, then it needs to be done fairly and across the board. If the British are to be presented with a bill for compensation, then so should the descendants of the inland African chiefs who sold other Africans to the slave-traders, as well as the descendants of the Arab slave-traders who sold on the slaves to the Europeans. They all profited too.

And it would only be fair if the British themselves sought compensation from the descendants of the pirates who raided Cornwall in the 1600s and carted off whole villages into slavery in North Africa. The fact is that yesterday’s oppressors were themselves often the day before yesterday’s victims.

Some years ago, a British diplomat recounted a conversation he had shortly after Nigeria’s independence with one of the country’s new rulers. The ruler was pressing the case for Britain to compensate the Nigerians for decades of colonial oppression. ‘I entirely agree’, the diplomat replied. ‘And you shall have your compensation – just as soon as we get ours from the Romans.’

So the case for the British making reparations for slavery does not add up. But why then is there this lust for self-condemnation by those here in Britain who support it?

Take the Church of England, which, in its rush to repentance, has committed itself to making reparations amounting to at least £100million and growing to £1billion for its supposed involvement in transatlantic slavery.

They have done so on grounds that are historically, empirically and morally spurious.

The Church Commissioners offered only unargued assumptions, most of which are untrue, that some wealthy benefactors who gave money to the Church ‘appeared’ to have made their fortunes from slave-trading.

On the flimsiest of evidence, they put their signatures to documents that assert that ‘the transatlantic slave economy played a central role in shaping the Church we have today’.

They make no mention at all of Anglican involvement in the campaign to abolish the slave-trade and slavery, and the subsequent work by missionaries, such as David Livingstone, who risked their lives endeavouring to end the slave trade in Africa. The present Church of England occupies cathedrals and churches seized by the state from Rome during the Reformation. Some of its present wealth was almost certainly squeezed out of overworked and under-rewarded medieval serfs and 19th-century industrial workers.

The question of which past wrongs to address and how best to address them is a complicated one that needs a careful answer. Yet, nowhere have the Church Commissioners felt it necessary to give one.

Instead they surrendered the matter entirely to an ‘Oversight Group’ whose members all shared the same basic assumptions, which they saw no need to subject to critical testing.

In the CofE’s desperation to appear ‘relevant’ in the 21st Century, they have trampled over the truth, a failure of due diligence that is truly shocking.

This, though, is but one symptom of a larger malaise infecting English-speaking countries that are former members of the British Empire. Prime ministers, archbishops, academics, editors and public broadcasters are all in the business of exaggerating our colonial sins against noble (not-so-very) savages. An obvious reason is the admirable and well-meaning inclination to correct racial injustices and so to ‘heal’ race relations. But that does not explain the reckless, dismissive brushing aside of concerns about the truth in the desperate rush to confess imaginary sins and do penance for them.

A prime example is Cambridge University theologian Michael Banner, who last year in his book Britain’s Slavery Debt makes clear his conviction that the British are systemically racist, and that this racism stems directly from colonialism and its epitome, slavery.

But why does Banner presume to project his own personal sense of guilt onto the national stage? Why does he paint the national picture in needlessly dark colours? Why is his reading about his own country’s colonial record and involvement in slavery confined to a casual handful of Left-wing sources?

I have no insight into his soul, but I observe that his bias is typical of his social class, one that typically considers patriotism to be vulgar at best and at worst ‘fascist’. Or to be more exact, it disdains English or British patriotism, but not Irish or Scottish nationalism – because they are anti-British.

George Orwell identified this trait over 80 years ago in 1941 when he noted: ‘England is perhaps the only great country whose intellectuals are ashamed of their own nationality. In Left-wing circles, it is always felt that there is something slightly disgraceful in being an Englishman and that it is a duty to snigger at every English institution.

‘It is a strange fact, but unquestionably true that almost any English intellectual would feel more ashamed of standing to attention during ‘God save the King’ than of stealing from a poor box.’

My complaint is that their criticism is entirely unrestrained by any sense of gratitude or loyalty towards the country that enables them to lead their privileged lives. They speak of it as if it had nothing to do with them, and cheerfully bite the national hand that feeds them, carelessly over-egging its sins and trashing its history, because they do not consider it their own.

They cover themselves in a cloak of self-righteousness, forgetting that, for Christians, the paradoxical mark of the genuinely righteous person is a profound awareness of their own unrighteousness.

The saint stands out as one who knows more deeply than others just what a sinner he really is. This tempers self-righteousness with compassion for fellow sinners, forbidding the righteous to cast the unrighteous beyond the human pale.

But in their case, humility is infected by pride and becomes nothing more than public virtue-signalling. It is a narcissistic, self-regarding display in which the self-proclaimed penitents hog the stage – and consign the alleged victims they proclaim to be supporting, be they African, Indian, or Arab, to nothing more than extras.

Lord Biggar is an Anglican priest and theologian. He was Regius Professor of Moral and Pastoral Theology at Oxford University

Adapted from Reparations by Nigel Biggar (Swift Press, £20). © Nigel Biggar 2025. To order a copy for £18 (offer valid to 20/09/25; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to www.mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937