Nations have been fighting, thieving, murdering and spying in Jerusalem for millennia. It is a city of secrets that straddles civilisations.

And, today, all the city’s covert – and not so covert – actors in the 21st century Great Game now unfurling across the Middle East are desperate to establish the answer to one inescapable question: What has happened to Iran‘s store of uranium?

Following the US’s spectacular June 22 strikes on Tehran’s nuclear facilities, President Trump declared that their infrastructure had been ‘completely and totally obliterated’.

But just days later, a leaked US Defence Intelligence Agency report estimated that, while the strikes had delayed the programme, it was only by a maximum of six months. This view is borne out by initial Israeli assessments.

But things could be far worse. The nuclear expert Dr Becky Alexis-Martin told my Apocalypse, Now? podcast today that it’s still possible Iran could muster together enough nuclear material to make bombs that would do as much damage as two Hiroshimas, the Japanese city in which 140,000 people died after it was hit by an atomic bomb in 1945.

It’s a terrifying thought. And one that is given added credence by findings from the James Martin Centre for Non-Proliferation Studies in Washington.

One of its directors, Jeffrey Lewis, said this week that the underground chambers at Iran’s key Fordow nuclear site that housed centrifuges to enrich uranium had probably survived the onslaught by the bunker-busters dropped by B-2 bombers.

Lewis also claimed that the underground facilities at the Isfahan complex had survived and, while the Natanz facility, a much larger enrichment site, had sustained the most damage, it had not been totally destroyed.

Satellite view of the Fordow nuclear site in Iran, which was bombed by US planes during a mission dubbed Operation Midnight Hammer

By Wednesday, even Trump was rowing back on his original assessment, conceding that the intelligence was ‘very inconclusive’.

If this is indeed the case, the world is facing a big problem. An enraged Islamic Republic with nuclear capability has more reason than ever to turn that capability into a nuclear weapon.

This week, I spoke to Yossi Kuperwasser, head of the Jerusalem-based Institute for Strategy (JISS) and former head of the Military Intelligence Research Division of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF).

‘Judging by the accuracy of the hit on Fordow, it seems the impact was considerable,’ he told me. ‘It may not have been completely obliterated, as Donald Trump [initially] claimed, but the damage looks severe. We’re talking about 144 tons of explosives from bunker-buster penetrators — an immense amount of heat and force.’

As well as being the lifeblood of any nuclear weapons programme, uranium is both the sword and shield of Iran’s military ambitions.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) estimates that, before the strikes, Iran held around 400kg of enriched uranium.

Even if the bunker-busting bomb strikes did succeed in penetrating the rock shields above the underground processing plants, there is evidence to suggest Iran moved at least some of its stockpiles of enriched uranium beforehand.

Satellite imagery released by U.S. defence contractor Maxar Technologies showed 16 trucks leaving the Fordow nuclear facility on June 19 – three days before the US bombs struck home.

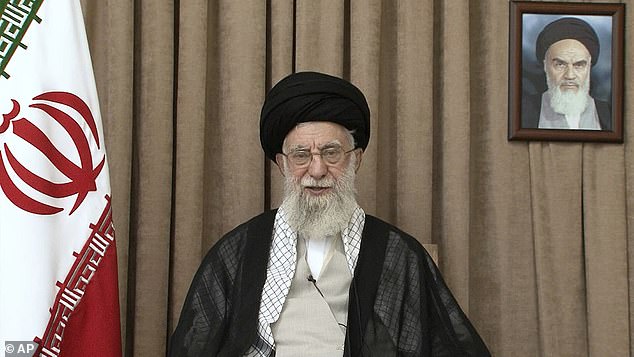

Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei

If that was indeed the uranium being shipped out, it would be unsurprising. Once hostilities broke out on June 13, the regime would have been delinquent in not safeguarding its radiological treasure.

And since the enriched uranium has not been confirmed as destroyed in the strikes, nor found, we can be confident that Iran still has it.

And even if it had been destroyed, there are reports that the Iranians also have ‘tons’ of 25 per cent enriched uranium – though that would take much longer to process into weapons-grade material.

The degree of enrichment is a key issue. Natural uranium contains less than 1 per cent of the fissile isotope U-235 — nowhere near enough to power the chain reaction that fuels a nuclear explosion. To do that, the uranium needs to be ‘enriched’ to the point where 90 per cent of it consists of U-235.

In order to turn their 400kg of 60 per cent enriched uranium into weapons-grade material, Iran’s nuclear scientists will need needs thousands of centrifuges, machines that spin uranium gas at ultra-high speeds to separate out the U-235 required for a nuclear bomb from the more common U-238.

Once the gaseous mixture has cooled back into a solid metal, it is shaped into a nuclear warhead. Iran’s 400kg of uranium is believed to be enough to create nine or ten nuclear-tipped missiles.

Many Israeli officials argue that Tehran had set up covert enrichment sites designed to keep the programme alive even if its main facilities were reduced to rubble.

Nuclear expert Sima Shine, a senior researcher at the Institute for National Security Studies, agrees. She reckons Iran is likely to be in possession of ‘hundreds, if not thousands’ of advanced centrifuges in a ‘hidden place’.

According to Jeffrey Lewis, a newly tunnelled site near the Natanz facility, which was not hit by the US air raid at the weekend, may have been created for just that purpose. Other reports suggest that the centrifuges and uranium could have been moved to ‘Mount Doom’, an underground facility 90 miles south of Fordow.

Donald Trump (pictured with US Defence Secretary Pete Hegseth) told reporters that Iran’s nuclear sites had been ‘obliterated’ at the Nato summit. However, leaked intelligence reports suggest Iran’s nuclear programme has been set back by only a few months

Lewis has said that the IAEA had been notified that Iran was developing an enrichment site at another secret location but that the Israeli bombing had started before the agency had been able to send in inspectors. Indeed, such is the controversy over Iran’s nuclear programme, IAEA inspectors have not visited the country’s major facilities for four years.

And if you want to hide enriched uranium, why not stash it somewhere no one is likely to bomb, or (better still) even look? This means not deep underground in Natanz or Fordow, but inside innocuous civilian sites such as telecom hubs or hydroelectric plants – or even, given the way Iran’s proxies Hamas and Hezbollah operate, in a mosque or a school.

Here the logic is brutal and simple: the US would hesitate to bomb infrastructure that it can’t prove is part of the nuclear programme.

However uranium and centrifuges are not the only constituent parts of a nuclear programme. Once a sufficient amount of enriched uranium has been stockpiled, the Iranians would then have to develop a reliable detonation system and a means of delivering the bomb to its target.

Iran’s scientists are good. We know this from the sophistication of their programme. But no credible intelligence sources argue that Iran has cracked the full suite of necessary technologies to mount a nuclear payload on a missile and detonate it when it reaches its destination.

This week scientists have suggested to me that it is more likely that the Iranians could cobble together something rather more rudimentary: a Radiological Dispersal Device (RDD), better known as a ‘dirty bomb’, possibly even using materials like cobalt-60 or caesium-137 from its civilian nuclear programme.

In such a device, the radioactive material would be combined with a conventional explosive – like dynamite or TNT – and, while it wouldn’t have the capacity to flatten cities, like a fully fledged nuclear weapon, it could create chaos.

The initial explosion would injure people within the blast radius but greater damage would come in the form of contaminated property, which would require a costly clean-up operation, and widespread fear and panic: not so much a Weapon of Mass Destruction as a Weapon of Mass Disruption.

Right now, a dirty bomb might be enough to slake Tehran’s thirst for revenge. But, as Dr Alexis-Martin says, something far worse can never be ruled out among the most extreme elements of the Iranian leadership.

While Israel remains the regime’s primary target, we in Britain must not get complacent – because we are in their sights, too.

Any nuclear stike or use of a dirty bomb would be a potentially catastrophic escalation by Iran, one that would almost certainly trigger massive retaliation from the West.

But the mullahs may well have the capability, and that is the point.

Centrifuges at the Natanz Uranium Enrichment Facility, which are used to make weapons-grade uranium

In the course of a series of investigations over the years into Iran’s malignant networks inside Britain, I’ve reported on our own ‘Little Tehran’, the network of regime-affiliated buildings that dot part of central London.

Let’s not forget that news of yet another Iranian terror plot on British soil broke only last month. Or that, since 2022, UK counter-terrorism police have identified more than 20 credible Iranian threats to kill or kidnap people here.

Just this week, the Business Secretary Jonathan Reynolds warned that Iran’s espionage operations in the UK are already ‘at a significant level’, adding: ‘It would be naïve to say that wouldn’t potentially increase.‘

I’ve written extensively about my frustration and bewilderment at the British government’s anaemic stance when it comes to the activities of the Islamic Republic. Nothing is more infuriating to me than its unyielding refusal to classify the country’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) as a terrorist organisation.

This despite the fact that, in January 2023, the House of Commons unanimously passed a motion calling on the UK government to finally proscribe the group. Yet that Commons motion was not binding and so the IRGC remains both unproscribed and active over here.

The Iranian nuclear game is now more fraught than it has ever been. Let’s hope that Keir Starmer starts to understand how high the stakes are now.

So far, Britain has stood apart, watching limply on the sidelines. It’s time to get involved beyond the rhetorical platitudes.

Iran is a wounded animal. The chance of it lashing out in a mindless display of rage is higher than ever. It is time we played our part in bringing it, finally, to heel.