Back when Michael Gove and I got engaged, friends expressed surprise that my fiance, arch-Eurosceptic that he was known to be, should have fallen for a girl like me, who grew up in Italy.

The answer then, as now, was that Michael wasn’t a sceptic in a Little Englander sense, believing that British was best. He loved Europe – especially its vineyards – but just didn’t want Britain to be run by an unelected cabal in Brussels.

I must confess, I’d always thought we Brits needed to lean in with Brussels. Get in there, gain influence, double down – and change things from the inside instead of flouncing off in a huff.

On a weekend break in Antwerp – one of the last happy memories I have of my marriage – it had even occurred to me that my husband could be the perfect person to turn around Britain’s relationship with the EU from the inside.

Blissfully tripping around the cobbled streets of this Belgian jewel, I fantasised happily about moving the family to Europe, about the kids learning to speak French, of returning to life as an expat. Little did I know that this was now becoming the furthest thing from my husband’s mind…

Michael never actually wanted a European referendum, especially so soon after the 2014 Scottish referendum, which was appallingly close. He’d always been very clear with Dave Cameron that referendums were dangerously polarising and created more problems than they resolved – and he advised very particularly against this one.

Nevertheless, Dave insisted that the eurosceptics would never quieten down unless they were thrown a bone, after which they could all, like the Scots, shut up for a generation (cue hollow laughter).

David Cameron ‘insisted that the eurosceptics would never quieten down unless they were thrown a bone’, says Sarah Vine in her new memoir. Pictured, the former prime minister resigning in 2016 after the Brexit vote

Which side would Michael support? My first stirrings of unease came in August 2015, on a break with friends in Norfolk. During that weekend, Michael was musing – in that abstract way of his – about whether the UK should actually stay in a trade organisation that didn’t seem to want to listen to it. Both our host and I tried hard to persuade him that he shouldn’t get carried away by thoughts of resistance to the Cameron/Osborne juggernaut. After all, the Remain verdict was a shoo-in.

‘Mhu-mmph. Mhu-mmph,’ said Michael. This is what I call his ‘listening-but-not-hearing sound’ – a beautifully conciliatory but opaque mixture of an affirmative yes-mm, a thoughtful hmmm and, finally, an ambiguous hmmph ending. It’s a sound that is Michael to a tee. Non-confrontational, not actually disagreeing, even (to the uninitiated) appearing to agree, but ultimately utterly non-committal.

Our host and I, however, were satisfied that we’d headed this particular Gove moment of intellectual free-ranging off at the pass. In the sunshine that day, there was nothing concrete about his stance, no outright opposition, merely a weighing-up.

There were certainly no nefarious plots, no gathering of dark forces, despite Nadine Dorries’s most torrid imaginings. Or at least if there were, I never had sight of them. Which is why, when Dave Cameron cornered me at teatime on New Year’s Eve 2015, I felt entirely relaxed.

We were cosied up – just the two of us – on the sofas in front of the large fire in the great hall at Chequers, idly chatting. ‘Everything’s going to be OK, isn’t it, Sarah?’ Dave said suddenly.

‘With Michael, I mean. And the referendum?’

‘Oh, I think so,’ I reassured him. ‘You know what Michael’s like.

‘He likes to noodle things through and he’s always believed that we needn’t be intimidated by life outside Europe, but ultimately he’s onside.’

I’d forgotten two crucial factors: Michael’s family background and his need to make a difference – to have a legacy.

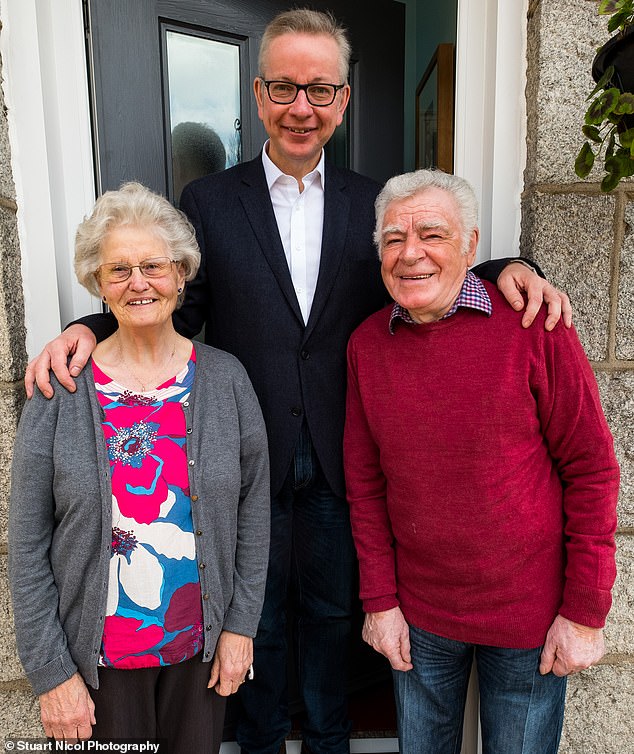

Michael Gove with his adoptive parents, Ernest and Christine

He adored his adoptive parents, Ernest and Christine, and always felt that he owed it to both them and society to make it big in life, to show that theirs wasn’t a poor choice, that he wasn’t going to waste this chance.

This wasn’t (just) the usual politician’s vanity but a yearning to stand tall for his parents – his saviours. In the 1980s, his father had been forced to sell his fish merchant’s business because of the EU and the common fisheries policy, and that had left a deep mark on the teenage Michael.

The idea that good, solid working men like Ernest, who’d never done anything but the right thing, could have their lives and livelihoods upended by flabby fat cats on the Continent rightly riled him.

As his wife, I should have understood Michael’s depth of feeling. But, possibly because of my own European slant, I failed to see how deep these particular waters ran.

In truth, it wasn’t as though he talked about the referendum an awful lot. Michael has always been a person who lives inside his own head: convivial, friendly, outgoing, yes, but also intensely private, fearsomely good at compartmentalising. He’s also deeply non-confrontational, so none of us should have been surprised that this apparent compliance with Project Referendum wasn’t quite what it should have been.

He’d always had the tendency to avoid conflict until the last possible moment, presenting contrary plans as a fait accompli, saying ‘Surprise!’ with a big smile.

When I asked him afterwards why he hadn’t at least discussed with me the way his thoughts were going, he flannelled me with talk of wanting to spare me the drama of it all. Which is somewhat ironic.

I tried time and again to introduce the subject of Dave and how, if Michael decided to openly support Leave, the consequences for our relationship with not just the Camerons but many other friends would be disastrous. I repeatedly urged him to have an honest conversation about it all with the PM, to really have it out with him, man to man. But the more I pushed, the more Michael retreated into himself.

If he’d just been honest with Dave and said, ‘Look mate, I know what you’re trying to do with this referendum and I totally get it, but what you have to understand about me is that the EU totally screwed over my dad, and he never quite recovered, and for that I can never forgive them so if you do go ahead, you need to know I won’t ever vote for those f***ers in Brussels’, I think Dave would have understood.

If Michael had made it personal, which it was, and which Dave certainly felt later, it might have been OK. Instead he made it political. Which was not OK.

But back to the Brexit countdown. In my stupidity, I felt not a qualm when the PM announced, in January 2016, that his Ministers could vote freely in the referendum. Yes, Michael had long had eurosceptic views, but he was, after all, one of Cameron’s right-hand men.

Silly me. Part of the trouble, of course, was that all Michael’s own right-hand men – Dominic Cummings, everyone around him – were committed Leavers.

So nearly all the opinions he was getting at work were one-sided. And I’ve often wondered if things wouldn’t have taken a different turn had Dave not deliberately humiliated Michael so publicly by demoting him to Chief Whip when he was Education Secretary.

After all, however unpopular his education reforms, Michael had been doing what Dave wanted him to do at considerable cost to his own political (and personal) capital. He’d agreed at first to the demotion but soon changed his mind.

In fact, we’d realised becoming Chief Whip not only meant Michael leaving the Cabinet, but – much more catastrophic, given the perilous state of our finances – that there’d be an annual pay cut of more than £36,000. Dave forced through the demotion anyway. By treating my husband the way he did, he demonstrated in no uncertain terms that he had no particular loyalty towards Michael, either as a friend or political ally.

That was the point, I think, when the shard of ice entered Michael’s heart. He would never have gone out of his way to damage the PM.

But when it came to something that truly mattered to him – in this case, the referendum – he wasn’t going to abandon his principles for someone who’d not only abandoned him, but also very deliberately fed him to the wolves to save his own skin.

Even so, the PM was not only his boss, he was also an old friend. It doesn’t get more awkward than that. By mid-February, Michael was locked in an internal struggle of agonising proportions. He talked to his father, spent hours on the phone with Dominic Cummings and MPs like Douglas Carswell (Ukip) and Owen Paterson (a leading eurosceptic). It was at this point we had dinner, arranged a few weeks earlier, with Boris Johnson and his then wife Marina at their house in Islington.

I had no sense at all on the night that momentous decisions were being made. I certainly didn’t know that Boris was having the grand existential crisis that he later claimed – although I obviously knew that Brexit was on the menu. Dinner was a succulent slow-roast lamb, as I recall, plus lashings of good red wine.

It was there, in the slight gloom of the dinner table lighting, that Boris and Michael noodled away, weighing up the pros and cons of Boris joining the Leave campaign. All those who’ve framed Boris’s decision as a kind of ill-thought-out whim will be disappointed to know that he was forensic in questioning not only the political practicalities of Leave, but also whether it was, in fact, legally possible. Timescales, economic consequences, trade options, regulations, Northern Ireland: these were all in the mix.

I saw no flibbertigibbetry that night, none whatsoever. Boris sought the counsel of various third parties – a Cabinet Minister, a lawyer – barking loudly into his mobile (on speakerphone) in between mouthfuls, Michael listening in and occasionally contributing. It really was a very lawyerly and quite technical conversation.

As we tucked into the roast lamb, Marina and I spent the next 20 minutes attempting to make dinner-party conversation with the other guests in stage whispers, Boris shushing us whenever we got too loud.

Just another tabletop tap dance around all the issues, I thought.

What astounds me once again, as I look back at this point, is my naivety. I knew Michael was struggling between his loyalty to Dave and his beliefs.

I could also see that Boris’s dilemma was more self-centred, concerned with what would be best for him, but I had no idea how personally they were all taking it.

For f***’s sake, Sarah, I’m fighting for my political life here’

Meanwhile, Downing Street had been drafting in some soft-skills agents – in the form of mutual friends – to work a Remain persuasion campaign through an onslaught of texts to us, even an invitation to drinks by Dave’s No 10 gatekeeper.

The message was becoming clear: don’t get above yourselves, you are foot soldiers, not ranking officers like us, so just get out over the top and do what we say, there’s a nice Gove.

That same week, a friend of mine happened to be at Frances Osborne’s birthday party. When talk turned to Michael’s possible defection, my friend overheard George Osborne spluttering: ‘But… but… we made Michael Gove. Who was he before? He owes us his whole bloody career! How can he not support us?’

Not only was this patently, foully, untrue, but never have I heard so pithily proved our eternal suspicion that neither Michael nor I were ever quite good enough for the public school nabobs who made up the true inner circle of David Cameron’s ruling elite.

Suddenly those cosy chats at Dorneywood, all those years of friendship, of school runs, of shared holidays, of helping out on every level, looked a little empty, two-dimensional.

But above all, this finally confirmed a very important and deeply depressing truth, one which I’d previously felt did not apply to us: there’s no such thing as a friend in politics. I felt stupid, used and humiliated. On Saturday, February 20, 2016, the Prime Minister announced that the EU referendum was going to be held on June 23.

Later that same day, the cross-party Vote Leave team was revealed. A friend tells me that Dave apparently became very emotional when he saw the list and – astonishingly – was reduced to tears when it was confirmed both Boris and Michael (who at this point was back in the Cabinet as Lord Chancellor) were on it.

A few days later, both we and the Camerons were invited to a mutual friend’s party. Michael was travelling separately and I happened to arrive at the same time as Sam and Dave, and we stepped into a lift together.

As the doors closed, Dave looked at me with daggers in his eyes and said, through clenched teeth, words that turned out to be the last I ever heard from him, face-to-face: ‘You have to get your husband off the airwaves, you have to get him under control. For f***’s sake, Sarah, I’m fighting for my political life here.’

For the first time since I’d known him, that charm and levity of touch that I associated with Dave was nowhere to be seen. He was angry, deadly serious, outraged even.

Also, for the first time, I felt the abyss of class between us. There was no attempt to speak to me as a friend or equal, no indication he wanted a proper conversation. This was an order, not a request, master to servant. And the quivering fury behind his voice, the anger in his eyes, was down to one thing and one thing alone: Michael was defying him. It wasn’t just that Dave didn’t like it. It was also that it didn’t compute.

He simply couldn’t understand why Michael, who on many issues was very much a team player, had on this occasion decided to defy him.

The answer, though he never understood it, was simple: Dave felt he was fighting for his political life. Michael, by contrast, was fighting for his political belief.

The two things are very different.

The very things Dave cared most about – his power, his reputation, his legacy – were the very things Michael was willing to sacrifice in pursuit of his own long-held belief that the better course for Britain was to leave the EU.

It’s been said there was no post-Brexit plan, but that’s not true. Vote Leave did have a plan. It was the personnel that was the issue.

Dave felt he was fighting for his political life. Michael, by contrast, was fighting for his political belief

The reason roles were not worked out beforehand was partly because Michael really never believed that Leave would win, but also because – to his mind – that would have seemed disrespectful of the PM.

Dom, Boris and Michael all assumed that Dave would stay on, no matter what the result – and that if, by some miracle, Brexit was the chosen outcome, they’d simply serve under him and under his direction.

It would be up to Dave to appoint whomever to whatever role in the process. Never would they have predicted that they’d be left in charge. Even on the day of the vote, when Michael had lunch with our friend Nick Boles, the two of them talked less about Brexit and more about the need, as Michael saw it, to pull back together as a party, regroup and heal.

The following morning, as we all know, the result was clear: the UK had voted to leave Europe.

Avoiding the paparazzi, Michael escaped from the back of the house like a spy on the run, speeding off to the Vote Leave HQ. I set off with the children on the school run, my stomach churning with anxiety about whether I’d bump into Sam Cameron.

By 8am, Michael was in Westminster, being clapped into the Vote Leave offices by equally dazed and overwhelmed activists. No time to take stock: just before 9am, the switchboard of Downing Street called. ‘The Prime Minister is on the line for the Secretary of State,’ said a disembodied voice. ‘Putting you through now.’ Observers still remember now how pale Michael went, how formal the call was, as the PM coldly conceded that the EU Referendum had been won by Vote Leave. There was no acknowledgement that they were friends, no mention of future planning. Forty minutes later, Dave resigned as PM. What a massive man-baby. What an impossible, irresponsible child, throwing his toys out of the pram because he hadn’t got his own way. It felt a bit like he would sooner bring the country down than let Leave have its victory. Et tu, Pontius Pilate – don’t forget to clean under the nails there as you wash those hands.

In the months and years afterwards, it almost amused me to see all the guff printed in the Cameroon politico memoirs – about how resigning was the honourable, only option.

Er, no. Abandoning the ship after you’d deliberately steered it into the iceberg was by no means the only option. The grown-up, statesmanlike thing to do would have been to go out there, say something along the lines of: ‘The British people have spoken and as your Prime Minister I have a duty to make sure your wishes are respected. I will therefore work with the leaders of the Leave campaign to begin the negotiations.’

He knew he had Michael and Boris’s support, because a few days before the vote, they’d both signed their names to a letter saying as much. But he just wasn’t big enough to park his vanity, his pride and his dogma.

Instead, Dave plunged the country into chaos. It was because of him, because of his inability to swallow this admittedly bitter pill, that we ended up with the disastrous Theresa May and that Brexit itself was so badly handled.

That, I’m afraid, was Dave’s legacy: offering the British people a choice then, when they made that choice, punishing them for it. But maybe it wasn’t entirely his fault. Every politician goes on a journey, you see, with the journey of a prime minister admittedly a particularly difficult one.

In a nutshell, you start out being a relatively normal human being, full of plans and ideas – and you end up quite bonkers, obsessed with very little else save your own survival and, failing that, your legacy.

It’s got nothing to do with character – even the best succumb. It’s just the nature of the beast.

Adapted from How Not To Be A Political Wife, by Sarah Vine (HarperCollins, £20), to be published June 19. © Sarah Vine 2025. To order a copy for £18 (offer valid to 14/06/25; UK p&p free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.

Flirty aide who had an affair with Sam Cam’s stepfather soon discovered the tribal nature of Clan Cameron

I always liked Rachel Whetstone – and Michael adored her for her gutsiness and her brains – but I found her quite hard work, at least in the beginning. She was Michael Howard’s political secretary when he was Tory leader and definitely a man’s woman, one of those girls who would always show up to supper in a pair of killer Gina heels, even if it was just a dull Tuesday night.

She wasn’t conventionally beautiful but she was very sexy, charismatic and forthright in her opinions – and argumentative in a way that seemed to endlessly stimulate the opposite sex. She would have Dave Cameron, George Osborne and the whole lot of them hanging off her every word, leaving us wives to attend to the domestics.

I have no doubt she would have played a key role in Dave’s tenure as Prime Minister had it not been for an event that knocked the stuffing out of everyone.

She and Sam’s stepfather, William Astor, had an affair. It wasn’t just some random encounter, either: it was a proper love affair, made even more extraordinary by the fact that Rachel was incredibly close to Sam and Dave.

She was godmother to their son Ivan, and omnipresent around their dinner table; but she was also close to Sam’s parents Annabel and William and a frequent visitor to their spectacular house in rural Oxfordshire.

Rachel Whetstone, Michael Howard’s political secretary when he was Tory leader, in 2006

Rachel and William had always got on like a house on fire: as a hereditary peer in the House of Lords, Conservative politics ran in his veins. But somehow, somewhere, their relationship had turned into something else – and it was quite the bombshell.

Their liaison came to light in the worst possible circumstances, while Rachel was holidaying with not only the Astors but the Camerons, at the Astors’ house on the Scottish island of Jura.

Launched upon this unsuspecting house party on August 17, 2004, was a lead item in the inimitable Richard Kay’s diary in the Daily Mail. ‘There is, I can reveal today,’ wrote Kay, ‘an intriguing romantic spring in the step of Rachel Whetstone, Tory leader Michael Howard’s political secretary and queen bee of the so-called Notting Hill set of bright young Conservatives. The Benenden-educated brunette, who is one of Mr Howard’s two most senior special advisers, has, I understand, formed a close friendship with a married older man who is a well-connected Tory grandee.’

The article went on to describe Rachel’s close ties with Dave and underlined the connection with his wife’s stepfather William. There was no specific mention of the affair, but the page was illustrated with a photograph of Annabel and William, with a drop-in shot of Rachel. It was a killer blow. I must confess I was utterly gobsmacked. I was no prude and certainly no stranger to the idea of one’s parents having affairs, my own having pursued a string of extra-marital divertissements over the years.

The parents of David Cameron’s wife – William and Annabel Astor

Still, this was quite something, even by their standards. Having fled Jura, Rachel swirled out of the political waters for good – and, unsurprisingly, out of her friendship with the Camerons. Understandably, Sam viewed her actions as an unforgivable betrayal of her and Dave’s trust.

As much as I understood the sense of anger and betrayal on Sam’s side, I also felt for Rachel.

After all, it takes two to tango, and while it’s never OK to go after a married man (or woman, for that matter), her punishment seemed harsher than his. William had his family and his title and his many palatial homes, and she was on her own in a small flat in Ladbroke Grove.

Frozen out of the political circles she had been such an integral part of, she now found herself a social pariah – a situation I was to recognise many years later, after the fallout from Brexit.

But Sam never forgave her and, even when Rachel and Steve Hilton (who went onto become strategy adviser to Cameron) finally got together – it seemed like he had been waiting forever in the wings – she and Dave were at best cordial with each other.

This was a prescient indication of the tribal nature of Clan Cameron: it was warm around the fire, but once you were out of that cosy circle it was icy.

Oh, the horror of the Brexit outfit that still follows me around the internet

For some reason it really didn’t cross my mind that anyone might take a picture of us as Michael and I went to vote on the day of the referendum and I wasn’t prepared. I looked truly dreadful.

Let us just savour the horror, shall we? A catastrophically see-through Marks & Spencer leopard-print top, paired with a jacket that was at least three sizes too small for me, a pair of three-quarter-length jersey palazzo pants and some very unflattering boots, which only served to highlight my ghostly and very possibly hairy white ankles.

Quite why I chose this ensemble for what was arguably the photocall of my life, I will never know. All I can say in my defence is that I wasn’t really thinking about it in those terms; in fact, I wasn’t really thinking ahead at all.

Sarah and her then-husband, Michael Gove, arrive at a polling station on the day of the EU referendum

Either way, I looked like I had not only got dressed in the dark, but out of a skip. It is, of course, absurdly narcissistic to dwell on it. But there is something about that image – along with so many of the paparazzi snaps that were taken of me during the period in the run-up to the vote – that just remind me of the unease, uncertainty and unhappiness of those weeks.

That picture has come back to haunt me countless times since, online and in print, a reminder not only that I have a very good face for radio but also of the craziness of those weeks and days.

Google me and it’s the first to pop up. It literally follows me around the internet like a particularly tenacious troll. If I look a little demented, grinning maniacally at the camera like a rabbit caught in the headlights, it’s because I am.

My stress levels were off the scale. I was eating and drinking too much just to keep going and sleeping far too little.

I was in bits emotionally. None of my friends were speaking to me. My family was furious with me. One of my uncles became so abusive on Facebook I actually had to block him and I’d had a terrible fight with my brother.

Newspapers and social media were awash with horrible stories about us and the trolls were out in full force. I wasn’t really in control, either of myself or the situation. All I could do was take it one day at a time and I made so many stupid mistakes; my judgment impaired not only by my emotions but also, if I’m honest, by fear and worry and a nagging sense that perhaps – just perhaps – none of this was quite right.