This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

Who are we really? If we pretend to be someone else, do we become that person? And if we do, what price do we — and those who believe us to be a different person — pay?

Such questions of identity have long been fertile ground for writers and directors.

Donnie Brasco is generally regarded as the gold standard in the undercover cop genre. Johnny Depp gave the performance of a lifetime in the 1997 gangster film. It told the true story of an FBI agent, Joseph D. Pistone, who infiltrates the mafia as a jewel thief. Pistone spent six years deep inside one of the world’s most dangerous crime dynasties.

His schizophrenic existence exacted a high price. He became inured to violence. His personality changed, putting a terrible strain on his family life. The mafia put a contract on him. Pistone and his family moved multiple times, and he now lives under an assumed name. But his work brought 100 Federal convictions.

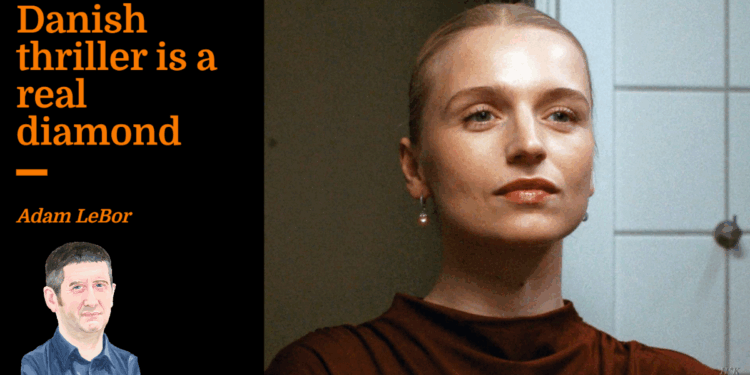

Diamonds, it seems, are a popular entry point for infiltrating organised crime gangs. In The Asset, an enthralling fictional six-part crime thriller now showing on Netflix, Tea Lind is not a jewel thief but the manager of a high-end jewellery shop in Copenhagen. Clara Dessau delivers a stand-out performance as Lind, a police officer recruited by the PET, the Danish intelligence service to infiltrate a highly dangerous criminal network.

Lind is a loner, with a fractured relationship with her mother, wary of emotional connections. She is an addict, attending a support group and seeking refuge in long runs. When the police suddenly remove her security clearance and her career comes to an end, the PET steps in.

It offers her a new role, infiltrating one of the city’s most powerful gangs, run by a man of Middle Eastern background called Miran, who supplies Copenhagen with much of its cocaine. Lind accepts.

She moves into a stylish apartment, paid for by the PET. She has all the spending money she needs to splash cash around nightclubs and buy herself a fancy new wardrobe. There is a glamorous launch at her shop, and she soon becomes a fixture amongst the city’s social elite.

But Lind is in danger. Her predecessor was murdered after Miran discovered that he was a PET agent.

Lind’s way into Miran’s gang is through befriending Ashley, his girlfriend. Lind senses Ashley’s vulnerability. She has everything she needs materially, but she knows that her comfortable lifestyle is paid for by the proceeds of bloodstained crime. She is desperate for someone genuine in her life.

What lifts The Asset above the legion of European crime series now streaming on the main channels is the series’ complex and engaging characters. Lind, especially, navigates a morally ambiguous landscape.

She is told to befriend Ashley and does so with ease. Ashley slowly comes to trust her new friend, whom she believes is called Sarah, and she starts to confide in her.

“Sarah” attends social events at Ashley and Miran’s home, all the while beaming back footage from a camera concealed in her handbag. She prowls around downstairs in the house seeking evidence of how the gang operates. At one gathering she is outside chatting with Miran’s brother Bambi, when he is shot dead. The directors steadily build up the tension, subtly layering each episode with questions about the ethics and morality of Lind’s mission.

It is clear that Ashley’s affection for Lind is genuine. Her daughter too becomes close to Lind, rushing to hug her when they meet. Lind agonises over her work. But her controllers care little for the emotional cost her mission is exacting.

Lind’s loyalties shift and blur until, inevitably, the situation spins out of control. The final twist is smart and unpredictable, setting everything up for — hopefully — a second season.

A House of Dynamite, also showing on Netflix, is a kind of thriller, but is so haunting that the film deserves a genre of its own. Kathryn Bigelow, the award-winning director of The Hurt Locker and Zero Dark Thirty, explores our deepest nightmare: that a nuclear war could start out of the blue, with no warning.

The film unfolds in a series of three sequences, each depicting the same 18 minutes, the amount of time it takes from launch to impact. The first unfolds in the White House situation room; the second in a Strategic Command base in Omaha; and the third from the perspective of the president, smartly played by Idris Elba.

Nobody knows why the missile has been launched and why Chicago has been targeted — which only adds to the tension. Protocols are implemented, counter-missiles fired, and there is a lot of shouting into telephones. What soon becomes clear is that the nuclear attack cannot be stopped.

The true horror is not portrayed with mushroom clouds or hurricanes of radioactive wind. Instead, it is the detail of human relationships that will soon end in a micro-second. The defence secretary, knowing that the missile will soon hit Chicago where his daughter lives, calls her one last time.

But she is busy with her new boyfriend and has little time to chat. He cannot of course say the words goodbye. Their exchange is unbearably poignant.

Some viewers have waxed indignant about the film’s ending. I won’t reveal the details. But the mark of a true auteur, as Bigelow is, is to create a story that lives on in the viewer’s head, long after the final frame. A House of Dynamite does this and much more.