This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

In 1726, Jonathan Swift published Gulliver’s Travels, a merciless satire of life in Georgian Britain that, thanks to his monumental genius, became an instant classic of English literature. The English poet and dramatist John Gay observed that it was “universally read, from the cabinet council to the nursery”.

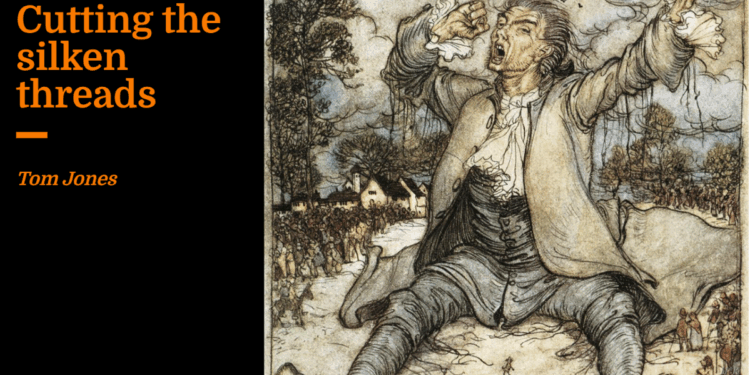

It might now deserve a place on the reading list of those who aspire to serve in the increasingly probable Reform government of 2029. In particular, they may gain something from revisiting Lilliput, where the gigantic Gulliver is held by a thousand silken threads as a metaphor for the petty constraints that bind Britain fast 299 years on.

Those tasked with shaping Reform policy do so in a country whose problems seem daunting for a party lacking an established infrastructure of think tanks, policy gurus, seasoned operators and the institutional memory of serving in government. Into this vacuum steps the Centre for a Better Britain, a new think tank that is ideologically committed to reform — if only the small-r kind.

CFABB is starting small. The Times reports that its aim was to raise £25m for “radical policy development”. Thus far, money has certainly not been wasted on luxury — its office in the Milbank Tower is convenient for Westminster, but has the thrown-together look that anyone who has visited a start-up will recognise: whiteboards with half-erased scribblings of future plans, teetering stacks of papers and a kettle in search of a kitchen.

So far, the staff headcount is less than five, but it is ticking upward. Since my visit in September new staff have arrived, although at this early stage the cavernous office perhaps befits their ambition more in its panoramic views over the Thames, rather than the output it generates.

When details of its launch leaked, the Financial Times branded it a “Reform UK think tank”. It is easy to understand this assumption: it is led by Jonathan Brown, a former Foreign Office diplomat who went on to serve as Reform’s Chief Operating Officer. But the reality is more nuanced. Non party-political, CFABB is part of a broader network that is sympathetic to Reform’s aims but not an adjunct of it.

Nimbleness is one contrast with traditional approaches. As James Orr, the chairman of CFABB’s advisory board, told me, Reform is not just disrupting Westminster with their politics, but also their speed of action. “As a start-up, they operate at a much faster pace than the conventional parties; Farage makes decisions on policies in minutes, rather than months. Westminster’s methodical think-tank cycle — commissioning research, editing reports, convening panels, publishing white papers — simply cannot keep up with leaders who decide policy positions as quickly as Reform.”

Jonathan Brown is keen to stress CFABB’s independence from Reform. Their self-assigned brief is not to churn out turquoise-tinged backsplanations for Farage’s campaign trail pronouncements, but to assemble “a serious policy platform capable of underpinning the radical change many voters now believe is overdue” — the very dissatisfaction upon which Reform is capitalising.

According to Brown, the organisation’s independence means it is able to draw on the advice of (and offer advice to) senior Tories and business voices that are interested in, but not within, the political realm. This signals not just a willingness to tap experience wherever it can be found, but of building networks within the sphere of new right thinking.

Deng Xiaoping’s aphorism “It matters not what colour the cat is, as long as it catches mice” was used often. CFABB seeks to be the first institution to position itself between Reform and the Tory right (indeed, there is so little space between them that one wonders whether anything can fit).

CFABB believes the national problems to be tackled are so systemic, crippling and entrenched that only a fundamental reordering of policy and governance can tackle them. Like Gulliver, the political will to act has been constrained by a thousand tiny silken threads, including the outsourcing of policy making to quangos, international law, civil service hostility, judicial overreach.

The line between political stasis and perceived indifference is perilously thin, and the inability of politicians to act is seen as unwillingness, which fuels a perception — rightly in some cases, wrongly in others — that the political establishment is unresponsive to democratic will.

Given the unresponsiveness of political institutions, is Britain still meaningfully a democracy?

The shortened time-horizon politics now operates in exacerbates the problem, as the spotlight of public attention is cast over single instances of outrage rather than structural problems. But it is a mismatch that has fuelled the declining faith in successive governments’ ability to deliver.

So what must change? CFABB’s first priorities are already set, and their first three workstreams will ask essential questions any post-Labour right-wing government must address. First, how could Britain respond to a fiscal crisis without raising tax? Second, if Britain is to have a secure, stable and independent energy supply, what does a post-Net Zero energy policy look like? Finally, given the unresponsiveness of political institutions to democratic mandates, is Britain still meaningfully a democracy?

Brown is realistic about what the sheer pace of politics means for the organisation. “We are prepared,” he says. “The Overton window is shifting rapidly on a range of issues and this opens up potential to explore radical policy options.”

But policy is only part of the picture. The hostility that met centre-right governments means planning for an incoming “small-r” reform government is as much about strategy as ideology. It is a stated aim to ensure any government hits the ground running. With a watchful eye across the Atlantic, many have seen the difference between Trump’s two terms; as Christopher Howarth, who is overseeing CFABB’s initial work on reforming government tells me, “It would be tragic if a new government wasted its term. The preparation needs to be done now.”

There are already signs that the lesson is being learnt; there is suspicion that Reform’s recent deportation plan was deliberately light on detail, not for want of insight, but to prevent giving those who would oppose it — both the Blob-backed migration charities via judicial means and the Civil Service via internal hostility — sufficient detail to create a plan to counter it. America had time; Britain may only have one shot.

There remain problems. As James Orr warned recently, an incoming government will have to force “nasty cough medicine down the country’s throat”. Doing what is necessary, particularly in fiscal terms, is unlikely to be popular. Will there be enough public support for such radical proposals? Brown believes that necessity may do the work for them, arguing that “headwinds can create their own force to overcome opposition”. Sophocles’s insistence that “there is no armour against necessity” may be a recognition of reality, but it is hardly a ringing call to arms.

Should a “big-R” Reform government take power there may also be internal rifts within its nascent policy development sphere, small as it is. Zia Yusuf (who sacked Brown shortly after arriving as party chairman) has been appointed head of policy, alongside heading up Reform’s DOGE unit. Reform’s biggest-name defector so far, Danny Kruger, has also been given the task of preparing the party for government.

Yet the Reform-whisperer, Gawain Towler, is sceptical of the idea that there will be much scope for internal rifts. He likens Reform’s periodic shedding of prominent members through internal division to a sabot, an ammunition system in which outer casings are fitted around a projectile to maximize propellant efficiency which then fall away once fired.

Reform, he says, will not just talk to CFABB. “There is no copyright on ideas. We’re talking to a lot of the existing think tanks already — Fix Britain, Prosperity Institute — and Reform can pick and choose on policy. People know where our hearts and our guts are when it comes to politics. It’s just a matter of linking them up to our brains.”

For a party so desperately in need of intellectual depth, internal discord this early is a serious vulnerability, particularly given Reform’s lack of government experience and policy expertise. Yusuf is currently “in the chair”, setting up Reform policy groups that will include a number of subject experts and draw heavily on think tank work. As head of policy, his role will be to oversee policy areas to ensure they don’t crash into each other, and to make a judgement call on priorities when they do.

Swift’s Gulliver, contrary to popular interpretation, does not break free of the Lilliputians’ bindings by his sheer strength. He is taken to Lilliput’s capital, Mildendo, and there bound with an iron chain around his ankle. The Lilliputians prove guardedly hospitable to Gulliver whilst he is useful, but when he refuses to reduce the neighbouring Blefuscu to a province he is charged with treason (including for public urination, though he was using his hose to put out a fire). To “untie the cords of the yoke” is not enough; only freeing yourself entirely from the control of those who hate you will suffice for freedom.