A new book illuminates what British Jews have brought to a rich architectural tradition

In the West, it seems that nothing is safe from identity politics. People, places and things have always had labels, but these tended to be more descriptive than anything. Country houses are a prime example of this; some were built with the proceeds of war or slavery, whilst others were built as military strongholds and still others by industrial revolution entrepreneurs. Yet historically our country houses were termed by their architectural style or period. That’s a Georgian house, we might say, or a Baroque palace, or an antebellum plantation.

However, it seems that identity politics has found its way into the niche world of country house history with the publication of an excellent, if thought-provoking new book on “Jewish Country Houses”. Apparently, it is now the religion or ethnicity of the families who lived in these houses that give them their identity. Take Waddesdon Manor in Buckinghamshire, for example; formerly known as one of the finest examples of Renaissance Revival architecture in the home counties. According to this book, what now makes Waddesdon (and indeed all of the houses featured in its glossy pages) distinctive is the fact that it was built by a Jewish family.

Although some other great country houses, such as the four “Whig houses” of Norfolk (Houghton, Holkham, Raynham and Wolterton) are recognised as the political powerhouses of the Whig party — they are first and foremost seen as prime examples of Palladian, neo-classical and Italianate architecture. So it is somewhat anomalous that the houses covered in this book are termed “Jewish”, as if that is their primary identity, and it is perhaps symbolic of the way that Jews have consistently tried to integrate yet have remained sidelined or ostracised by society at large.

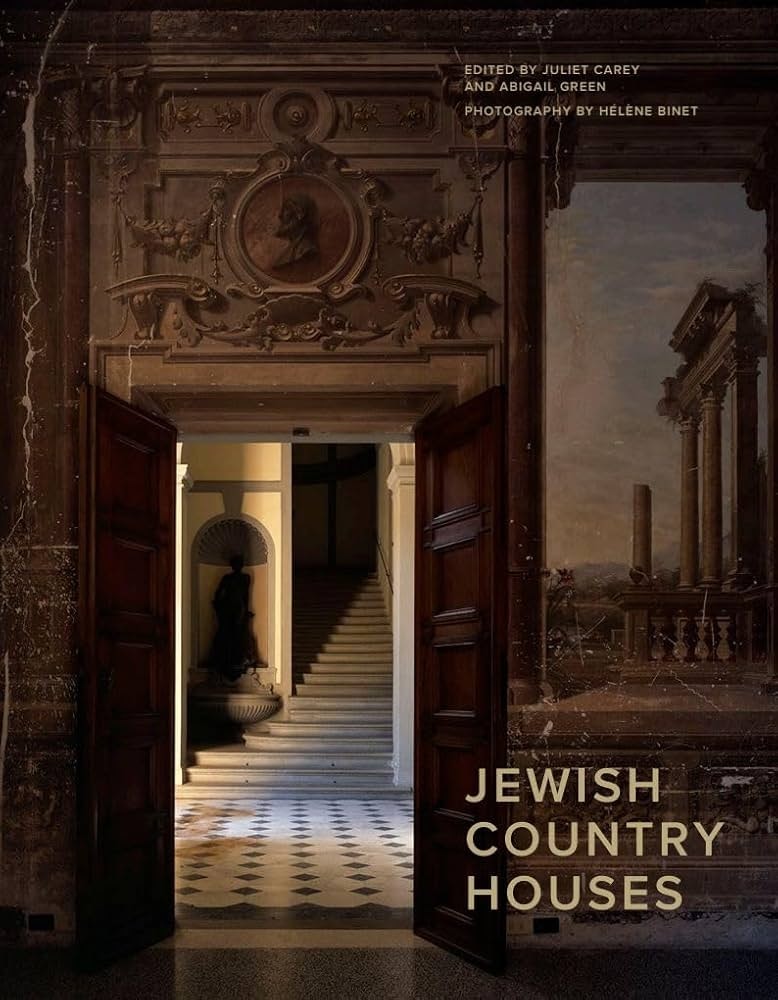

Jewish Country Houses is the culmination of a four-year long project at Oxford University and consists of a series of essays and case studies written by a star lineup of historians — masterfully edited and curated by Juliet Carey and Abigail Green. Meticulously researched and richly illustrated, this book — which falls somewhere between an academic tome and a glossy coffee table publication — explores the country houses owned, built, or renewed by Jewish families across Europe and the United States over the past few centuries. It offers a nuanced perspective on how these houses reflect the complexities of Jewish integration, identity, and heritage from the 19th century onwards.

Spanning the West from Prussia and the Mediterranean to Pennsylvania and Newport, Rhode Island, the case studies include Schloss Freienwalde (the home of Germany’s first and only Jewish Foreign Minister, Walther Rathenau, who was assassinated in 1922), Villa Kérylos on the French Riviera and Frank Lloyd Wright’s iconic “Fallingwater” built for the Kaufmann family. Each essay explores the architectural significance of these houses and the histories of their Jewish owners, many of whom played pivotal roles in the public square.

One of the book’s strengths lies in its ability to challenge traditional notions of what constitutes a “Jewish country house”. Green, Carey and the various contributors explore the nuances of cultural assimilation and identity, questioning whether these homes should be viewed purely as symbols of Jewish heritage or as representations of broader societal integration. This investigative approach adds depth to the architectural and historical analysis, prompting us to reflect on the nature of cultural identity.

The volume is beautifully illustrated, featuring both historical images and commissioned photography by Hélène Binet. Binet captures the essence of these country houses, highlighting both their architectural features and the personal stories that haunt their walls. Combining visual treats with succinct, scholarly essays, allows what would otherwise be a dense and academic book to be delightfully readable, the images serving to provide us with a visual connection to the subjects discussed.

Of the fourteen case studies, the first thirteen look at houses in Europe. These are by no means the only Jewish country houses in Europe, but each has been selected for its significance; from Hughenden Manor (home of Disraeli, Britain’s first and only Jewish Prime Minister) to Château de Ferrières (another of the great Rothschild powerhouses). The fourteenth and final case study looks across the pond to the US, where the editors contribute their own chapter by offering a comparative analysis that illustrates how American Jews adapted the European country house tradition to reflect their own unique experiences and trepidations. The inclusion of this chapter underscores the transatlantic nature of Jewish cultural and architectural expression, and feeds into the broader debate surrounding the creation of the state of Israel as a homeland for Jews.

It not only documents the architectural beauty of these houses, but also delves into the personal and communal narratives that shaped them

From a scholarly perspective, this book is rigorous and dense. Yet the short chapters and aesthetic appeal make it readable and enjoyable. It succeeds in shedding light on a previously overlooked aspect of country house history, exploring themes of prejudice, identity, assimilation and the relentless search for “home”. The book also acknowledges the impact of the Holocaust on country houses and their owners, adding a layer of poignancy to the narrative by reminding us of the fragility of cultural achievements in the face of societal upheaval. This presents a challenge to all of us in these uncertain times — a challenge for us not to take for granted the beauty of our architectural heritage; for it takes years to build something beautiful, and seconds to tear it down.

With antisemitism on the rise across the West, coupled with the politics of envy that is rife in places like Britain, it may seem unlikely that a hefty new volume on great country houses built by Jewish families (the Rothschilds in particular) is going to do much for their cause. Yet this book is undoubtedly a significant contribution to the fields of architectural history and Jewish studies. It not only documents the architectural beauty of these houses, but also delves into the personal and communal narratives that shaped them, ultimately helping us to make sense of the Jewish longing for a place to call “home”.