Sometimes I feel very sorry for Prince Harry, and sometimes I very much do not.

Watching him walk across an Angolan minefield this week, with his expression set to Hollywood-wattage-warzone-grim, caused a mixture of emotions in my calloused heart.

Yes, you could see the shadow of the bereaved little boy whose life has been forever fractured by the death of his mother.

We hardly need reminding that he was ‘showing up and doing good’, to paraphrase the self-congratulatory Archewell mantra that smokes through his new life like a cloud of look-at-me.

Twenty-eight years after Princess Diana made her famous landmine appeal, here was Harry making an equally perilous pilgrimage down a dust track – for the third time.

On the one hand, good for him. The Halo Trust charity still needs support and money. The important work of landmine clearing goes on. Yet, on the other, how many times is Harry going to pull the Mum Card out of his back pocket?

No wonder so many of us raise our eyebrows and think: ‘Oh God, here we go again.’ It is all so performative, so copycat, so showtime.

Since leaving the UK in 2020, Harry has often said that he wants a new life. Yet, like an arsonist who cannot resist returning to the scene of the fire, he constantly intrudes back into his old life, raking though these bittersweet embers of remembrance.

, making an equally perilous pilgrimage down a dust track – for the third time

Prince Harry in Angola yesterday to recreate his mother’s historic landmine walk from 1997, making an equally perilous pilgrimage down a dust track – for the third time

Twenty-eight years ago, Princess Diana Princess put the Halo Trust on the charity map with her walk that changed the world, raising awareness of the terrible impact of landmines on human life

Why? Perhaps because, after five years of attempting to establish himself as a major player and philanthropic grandee in America, his old life and royal identity are still all that carry any international resonance.

Look at him, bootlegging his own mother, while trying to carve out a royal status of his own in a poor African country where a third of the population lives below the poverty line. It is almost pitiful.

Along with James Cowan, the chief executive of the Halo Trust, the prince had meetings with João Lourenço, the president of Angola, during which a pledge for a ‘significant’ three-year programme of further support was secured.

As is usual with any venture involving the Duke and Duchess of Sussex, financial details came there none. For Harry is nothing if not Casper the Friendly Ghost when it comes to global humanitarianism – floating around in a well-meaning and empathetic way, but always vague on the details.

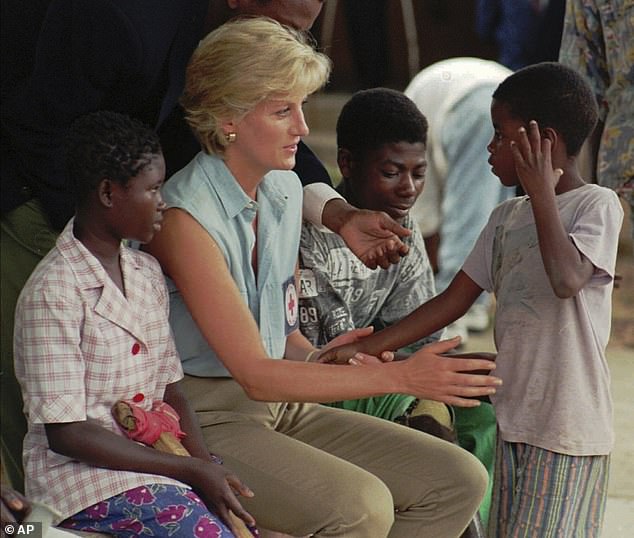

The Duke of Sussex with children in a remote village near Africa’s largest remaining minefield as part of HALO’s community outreach programme

During this visit he did not shy away from stating the obvious with the gravity of a tribal leader confronting the gods of misfortune.

‘Children should never have to live in fear of playing outside or walking to school,’ he said – no doubt with that pained, strained Harry expression suggesting a weary acceptance that the burden to save the world is his alone to carry. It is either that or constipation.

Heaven knows what William must think of it all. Here in the UK, the Prince of Wales does not have his problems to seek.

Both his father and his wife have been ill with cancer, he has three young children to marshal through the complexities of royal life, and it is upon his shoulders that the entire future of the British monarchy rests.

A burden undeniably made more difficult by the lack of support from the Duke of Sussex.

How must the king-in-waiting feel, watching his younger brother cosplay their mother’s campaigns without swallowing any of the responsibility that comes with being a Windsor? Not entirely thrilled, I would venture.

While in Angola, Harry also attended a reception at the British Embassy, one of those hot-air pow-wows where he met leaders from the business community to discuss ‘the importance of continued partnership in humanitarian work’ – whatever that might mean.

In other words, it was a royal visit in all but name.

Perhaps I should be more generous about this display of charitable concern from a nepo-baby millionaire who lives in a Californian mansion, and who could spend his days doing nothing more taxing than playing on the beach and eating flower-sprinkled meals prepared by his lovely wife.

But it is hard. So hard! And not just because – despite Harry’s measures to ‘offset’ his carbon emissions – flying across the world and roaring through the African countryside gives the impression to some of us that he is happy to quieten his oft-bleated concerns about climate change when it suits his own purpose.

There is also the suspicion that paying such high-profile homage to his long-dead mother is a handy way of stitching some of her glory on to his own tattered freedom flag.

The Princess of Wales with young Angolan amputees who lost their limbs due to landmines at the Neves Bendinha Orthopedic Workshop in the outskirts of Luanda

Not to mention that the notorious landmine walk is heavy with the implication that Prince Harry is putting himself in danger for humanity’s sake – when the reality is that the cleared path is probably safer than trying to cross London’s Putney High Street on a busy Saturday afternoon.

Let’s hope so, at least. Otherwise, it makes a mockery of the prince’s recent multi-million-pound legal battle about his downgraded security arrangements in the UK, which he insisted put his life at risk.

Yet Harry has to find something to do that tallies with his vision of himself as a humanitarian of note, someone who is changing the world for the better.

After all, his African charity Sentebale has blown up amid accusations of ‘unthinkable infighting’ and the last public footage released of him showed him doing the robot dance with his twerking wife in a hospital delivery room.

Raising the global profile of Angola and its terrible landmine problem is Diana’s legacy – what on earth is Prince Harry’s going to be?