This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

In 2021, Oxford University Press (OUP) changed its logo. In a move widely critiqued on Twitter-now-X and at any number of academic conferences, the world’s largest university press replaced its distinctive 16th century folio stamp with a plain serif rendering of the company’s name. The spoked icon which replaces, in the new logo, the first “O” of Oxford is — apparently — reminiscent of the turning pages of a book whilst representing the company’s “journey of digital transformation”.

Indeed, this new logo is more than just another casualty in the minimalist epidemic sweeping the branding world. Rather, it is a self-conscious marker of OUP’s digital-first publishing strategy and indicative of the shift within academic publishing from print to digital production.

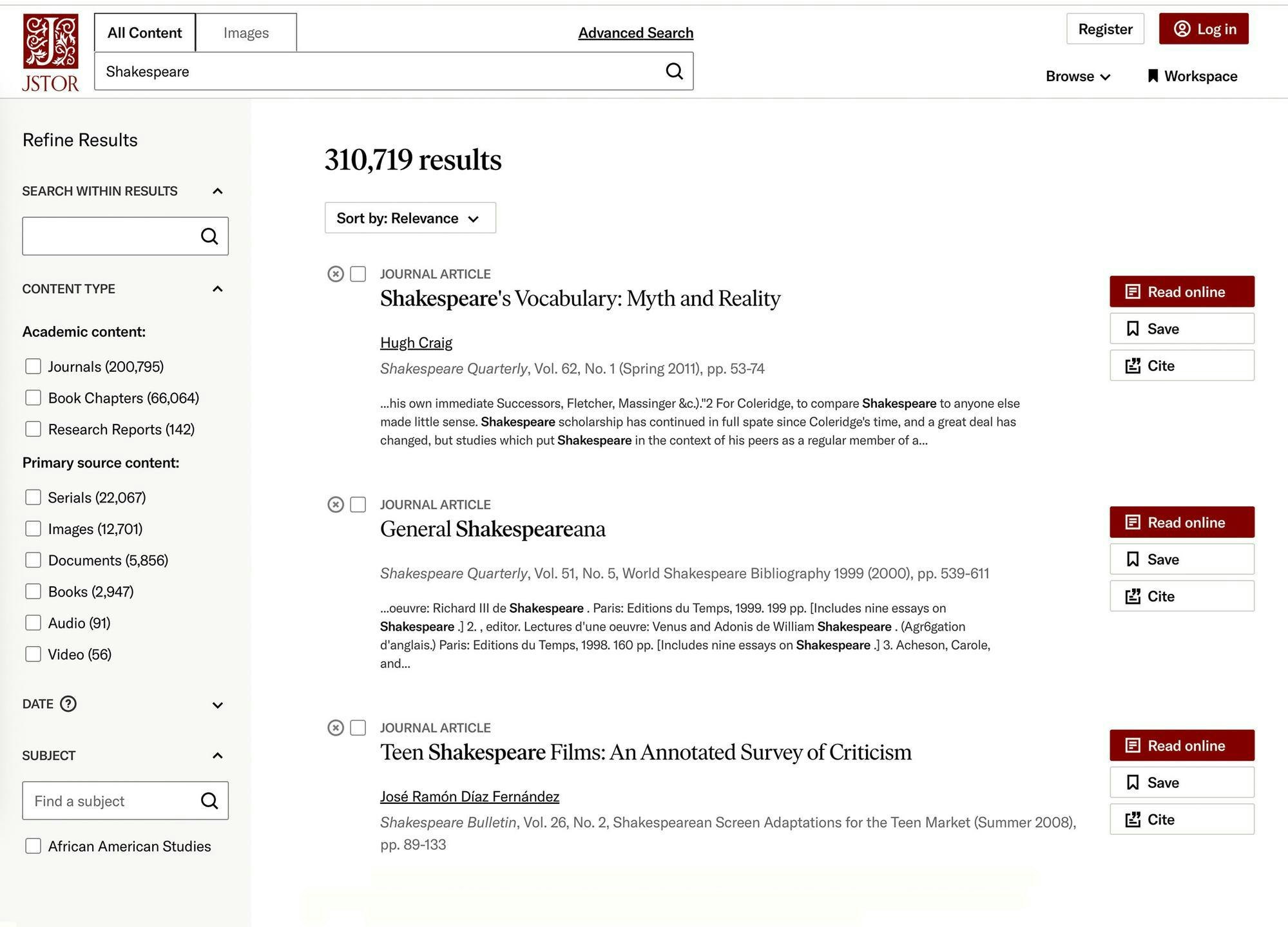

There have been two digital revolutions in academic publishing. The first came in the 1990s and focused on preservation. JSTOR pioneered the digitisation of print journals, and this practice was adopted by academic publishers throughout the 1990s and 2000s.

Notably, digital content in this context followed the pattern of printed books and journals, which continued to be published physically before being uploaded to whichever online platform the publisher chose.

In the last decade, however, digital publishing has taken on a distinctly new edge. Pearson made headlines in 2019 by announcing their digital-first publishing strategy, and other major publishers — including Cambridge University Press (CUP), Springer Nature, Yale University Press, OUP and Taylor & Francis — have followed suit. Digital-first publication sees scholarly materials published initially or exclusively in digital formats.

Where previously, digital publication replicated physical works, the digital-first strategy firmly places the physical production, presentation and preservation of scholarly works in second seat. This changing prioritisation is clear in the declining quality of printed texts. Though many presses retain some form of print production for books, there is a trend towards print-on-demand.

This has seen a general elimination of embossed covers, dust jackets and sewn bindings. Misaligned margins, low paper grain and fuzzy text reproduction now mark many print-on-demand books. They are becoming what ebooks used to be: poor facsimiles of the primary published material (now digital texts). The vast majority of journals are no longer printed at all.

This isn’t just a matter of aesthetics. The shift from physical to digital production ultimately revalues and devalues the material published. Scholarly output is redefined as “content” to be packaged and sold, rather than as discrete knowledge productions with which to engage.

Academic publishers bundle ebooks and ejournals into collections and present these as “scholarship portfolios”, “online academic products”, “digital scholarship collections” and so on. The products sold by a given academic press are now these tranches of publications, rather than individual publications themselves.

Purchase and subscription models are constructed to discourage title-by-title sales, and marketing materials highlight the quantity of texts included in any product, rather than the titles which make up that quantity. Books and journals are approached as constituent parts of these tranches — each a useful addition to a collection, but not individually valuable to either publisher or buyer.

At its root, this is a funding issue. As academic publishing has, like the whole higher education enterprise, become more corporate, strategy is determined increasingly by funding sources and profit potential. On the other side of the market stall, libraries are primarily budget-motivated: as their budgets are slashed by university administrators, their priority is to cost-effectively acquire relevant material. At the head of the supply chain are researchers, who operate in a publish-or-perish environment where job funding is often reliant upon publication quantity.

A further factor in the funding quagmire is the altruistic notion of open access publishing, which both relies upon digital-only channels and carries the implicit notion that digital publishing is essentially free (because there are no physical production costs). But, there is no such thing as free research; there is always a cost for publication. Open access publishing flips that cost from customers, who pay to read, to researchers and research bodies which pay to publish.

Monographs and edited volumes are, in this market, dead weight. They take time to commission, write and edit. They are not regularly updated and so render few upselling opportunities; they are niche and thus difficult to package into larger products. As they often represent years of work and don’t rest on the very edge of the scholarly curve, they don’t register as high-impact publications, limiting open access funding and library budget allocations.

Short-form scholarship, on the other hand, is low-cost and almost endlessly saleable. Journals compile reactive research, which registers high for relevance. Journals that are not published open access lend themselves favourably to subscription selling, whilst journal collections cover broad subject areas whilst retaining specificity on a journal-level, prices can be increased each year, and back editions can be packaged up in tranches and resold as archives.

This funding landscape shapes a publishing culture in which presses are motivated to publish as much short-form content as possible in order to maximise profit via external funding and subscription sales. This has led to an inevitable decline in editorial rigour. Though the scandals of obviously AI-generated articles published by high-reputation academic journals are amusing, they serve as a stark caution against a publishing culture which values scholarship as content, rather than as knowledge production.

In order to maximise revenue and manage the vast and rapidly-updating digital collections which result from the prioritisation of high-turnover digital content, academic publishers have invested in creating exclusive digital publishing infrastructures. Cambridge Core, Oxford Academic and Pearson Collections, amongst others, are gated digital platforms on which these individual presses host their own publications. Most academic presses also have licensing agreements for select products with other for-profit digital publishing platforms such as JSTOR and EBSCOhost.

In this way, digital-first publishing has radically changed the function of libraries in the academic sphere. Whilst for millennia, libraries have acted as repositories of knowledge — through the books and journals they owned and loaned — they are now gateways through which digital content can be accessed. In moving to digital-first publication, presses retain almost complete ownership and control over the work they publish.

This poses a risk to the reliable and lasting access to scholarship which physical publications used to ensure. Publishers can handle, and mishandle, the scholarship they retain as they wish. This freedom, along with an incautious embrace of fragile digital publishing platforms betrays again the devaluation of scholarship brought by digital-first strategies.

Digitally-published works can be edited and erased less traceably than printed texts. In theory, digital object identifiers (DOIs) should mark out and store official versions of record for ejournals articles and ebooks. However, despite calls for standardised archives, the predominance of press-specific publishing platforms means there are few shared systems for DOI cataloguing.

Publishers remove digital works from their online platforms regularly as a result of various factors (author request, discredited content or rights conflicts, for example). Such erasure disrupts research in a way that print discontinuations do not. Once a piece of exclusive content is removed or altered on a publisher’s site, even if the original exists in a DOI archive, there is no way for a researcher to access it. Content exclusively published online can vanish from the research landscape in a way that printed texts, which have a habit of turning up in obscure libraries, rarely do.

Though the risk of digital erasure by publishers themselves is concerning, the risk posed by fragile digital publishing systems is more substantial. In 2022, the British Library’s online catalogues were taken hostage by the Rhysida hacker group, wreaking near-total havoc on the Library’s ability to function. The 170 million items held by the Library, along with their digitised texts, were inaccessible for months as their computerised catalogue was corrupted.

At the time, much was written in the library sector about the risks hackers pose to digital collections, but little has been done by academic publishers themselves. At the publishing house for which I work, senior leaders issued a concise response to questions raised about the stability of our digital publication platform: in short, we would just have to hope our security was stronger than that of the British Library.

It doesn’t even take malevolent hacking to disrupt digital publishing. A brief glance through any research technology or library forum reveals how regularly publishing platforms malfunction. Predominant amongst the digital gremlins are access faults — login failures, multi-factor authentication glitches or regional incompatibilities. Librarians are every day battling for their researchers to have access to the scholarship for which they have paid.

The predominance of exclusive digital publishing platforms increases the threat posed by both hackers and gremlins. As publishers seek to gatekeep access to their publications, there is an increased likelihood that if a publishing platform crashes, the works held on it could be lost entirely.

A commitment to digital-first publishing, without an equal commitment to ensuring the work published is secure and accessible, ultimately underscores the issue of devaluation. If one article goes missing, if one text is inaccessible, if one platform is down for a day, no matter: it’s just content; there will be more. Nowhere is this lack of regard for the security and value of the scholarship they publish clearer than in the academic publishing establishment’s response to generative AI.

Presses have overwhelmingly taken the opportunity to rake in more profits by licensing the use of their digital texts to train large language models (LLMs). Wiley sold access to “select, previously published content” to train LLMs without its authors consent, as did Taylor & Francis and OUP. CUP took a different approach, issuing new rights agreements for AI licensing specifically and offering a 20 per cent royalty to authors who opted in.

CUP conceded that AI trawling of its publications was inevitable and suggested that in opting in to the licensing agreement, authors could at least expect revenue and regulation. Indeed, the trawling of pirated works has already resulted in several lawsuits, highlighting the risks posed both by AI and insecure digital platforms. Significantly, CUP responded negatively to a UK government proposal that AI companies be given total access to digitally-published work unless authors opted out. As the company is clearly not against the use of its material in training LLMs, it must be concluded that this response was rooted in the loss of profit such a move would represent.

This licensing-for-profit approach is entirely short-sighted: once AI has trawled published content and can provide it upon request, there will be an inevitable usage and subsequent profit drop-off, as researchers won’t need to visit the paywalled publishing platforms directly. But, more significantly, it is another area in which profit is placed above pedagogy, and in which digital publishing corrupts the nature of scholarly works.

AI trawling neither discriminates between scholarly works nor treats them as anything beyond data sets. Scholarship is dismantled and reconstituted by LLMs to respond to search prompts, obscuring the context and effort of its authors. As academic publishers license their digital publications for AI data-gathering, they concede their low view of the work they publish: its value is in profit generation, not in its contribution to scholarship or the breadth and depth of its analysis.

Where does this leave us? Digital-first publishing has redefined scholarly output as content to be repackaged, sold and erased whilst AI is gripping the minds and essays of our undergraduates. Meanwhile, money continues to pivot the scholarly world towards high-turnover, low-quality publications. Should we concede the breakdown of the writer-publisher-reader relationship? Is there any scope for a change of direction?

There will be a future for academic publishers, so long as there is money to be made. Whether there is a future for scholarly work within academic publishing is another question entirely — one to which there is no clear answer.