This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

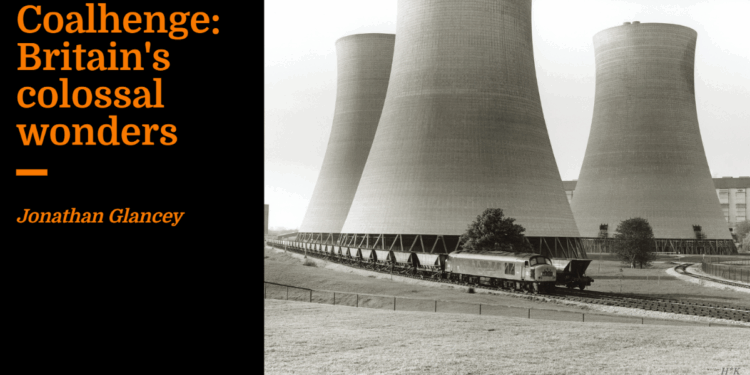

Cresting a hill at sunset on an unfamiliar dual carriageway south of Nottingham, the stupendous view ahead was such that I wanted to stop there and then to take it in. A slip road under a cat’s cradle of high voltage wires allowing an escape from tailgating, rush-hour traffic, led through a knot of roundabouts to East Midlands Parkway, an isolated station on the Sheffield to St Pancras main line set cheek-by-jowl with eight colossal concrete cooling towers.

These awe-inspiring structures, each taller than St Paul’s Cathedral and three times the diameter of its inner dome, were what had caught my eye. Now, I knew where I was. This was Ratcliffe-on-Soar power station, closed in September 2024 and the last of its English coal-powered kind. King Coal may have been dethroned here, yet he has left monuments in his wake that some, if not all of us, can only look on with awe.

Not so long ago, there were some 240 of these giant towers sited, for the most part, in the former realms of Lancashire, Yorkshire and Midlands coalfields. Just 37 remain and, immune from listing, they are likely to be extinct by 2030. Certainly, Historic England is no friend to them, telling governments that they “do not have the architectural interest requisite for listing”.

This sentiment helps to get around the fact that despite their artistry, cooling towers were the work not of “interesting” architects but of skilled engineers. And what engineers they were: the concrete shells of these immensely tall and strong hyperboloid structures are just seven inches thick, the ratio of their diameter to the thickness (or thinness) of their walls less than that of an eggshell.

In a foreword to the Twentieth Century Society’s suitably massive book Cooling Towers: A Celebration of Sculptural Beauty, Industrial History and Architectural Legacy (2025), Sir Antony Gormley sees them as “twentieth-century equivalents of Stonehenge”. To the sculptor’s Stonehenge, we might add the abandoned abbeys of Rievaulx, Fountains and Tintern, the sight of solitary hilltop chapels like St Catherine’s, Abbotsbury, and windmills, cotton mills and great railway viaducts, many abandoned since the Beeching axe, wielded at the very time the mighty CEGB (Central Electricity Generating Board) coal power stations and their cooling towers were built.

Then there are the Iron Age brochs of Scotland, those stone roundhouses facing fierce northerly seas. How many of those who have visited the well-preserved, funnel-like broch on the Shetland island of Mousa have drawn the comparison with a cooling tower? The Broch of Mousa is a fine work of stone construction and engineering and for countless generations home to storm petrels, a glorious sight as they swarm back here in their thousands from far reaches of ocean and sea that somehow evokes the elemental beauty of clouds shaped by water vapour escaping from cooling towers sailing over wide landscapes.

When, in the 1960s, the CEGB built its giant power stations, it employed architects and landscape designers of the highest calibre. I think of the now-demolished Didcot power station in Oxfordshire, once a mesmerising landmark seen from train windows whose consultant architect was Frederick Gibberd, busy at the time with Liverpool’s Metropolitan Cathedral of Christ the King. Like a giant Gemini space capsule in some lights, an ecclesiastical cooling tower in others, one of the cathedral’s nicknames is, appropriately, the “Mersey Funnel”. Gibberd’s structural engineers at Liverpool were James Lowe and Jack Rodin; one of Rodin’s first jobs was resident engineer at the hydro-electric plant, Pitlochry.

Gibberd is said to have discussed the arrangement of the siting of the Didcot cooling towers with Henry Moore. In the design of Ironbridge B power station sited in Shropshire’s Ironbridge Gorge, project architect Alan Clark and landscape architect Kenneth Booth had the concrete of cooling towers pigmented with iron oxide, giving them the reddish hue of the local soil. These power stations were designed with artistry and flair.

Those who find these 1960s temples of power and their attendant cooling towers blots on our landscape or berate them for being coal-age behemoths deserving demolition may want to take a breath and think of how tastes and attitudes to powerful engineering structures change.

When, in the early 1860s, the Monsal Viaduct, designed by William Barlow of St Pancras trainshed fame, was built to carry the Midland Railway over the Wye Valley, John Ruskin was furious. In one of his Fors Clavigera: Letters to the Workmen and Labourers of Great Britain, the indignant critic wrote, “There was a rocky valley between Buxton and Bakewell, once upon a time, divine as the Vale of Tempe … You Enterprised a Railroad through the valley — you blasted its rocks away, heaped thousands of tons of shale into its lovely stream. The valley is gone, and the Gods with it; and now, every fool in Buxton can be in Bakewell in half an hour, and every fool in Bakewell at Buxton; which you think a lucrative process of exchange — you Fools everywhere.” Today, Barlow’s viaduct — the railway line it served was closed by Barbara Castle in 1968 — is a much-loved feature of this Apolline landscape and, with luck, may yet shoulder trains again.

It was only when home from Nottingham that I found out that the fast road the Ratcliffe towers command is the A453. It was named Remembrance Way when it was realised that the road bore the same number as that of the then total of British mililtary losses between 2006 and 2014 in Afghanistan (the tally has since increased to 457). If I had come in summer, it would have been lined with blood-red poppies, with the cooling towers conjuring the mountain backdrop of Helmand Province where most of those soldiers died.

I remembered driving north out of Authuille in the Somme on the D151 one early morning through sun-tinged November mist; as the road climbed and turned, I caught sight of that magnificent, architecturally daring and haunting monument by Edwin Lutyens, the Memorial to the Missing of the Somme. The sight of the cooling towers at Ratcliffe-on-Soar had been equally poignant. Whilst there is no question of Lutyens’ monuments facing the wrecker’s ball, the Ratcliffe towers seem doomed.

What, though, if the Ratcliffe towers were to be designated a national monument and joined through the Trent meadows to the nearby Attenborough Nature Reserve, with its booming and newly breeding bitterns, otters and winter wildfowl? We could have all this natural beauty, a proposed new zero-carbon manufacturing and technology centre at Ratcliffe and the cooling towers. What a precedent this could set for the sites of other threatened cooling towers.

Might such a proposal win public favour? In Derbyshire, not far from neolithic henges, the five cooling towers of Willington power station, closed in 1999, still stand. They feature on the badge of the local football club and on the school crest of the village’s primary school. Peregrine falcons survey the landscape from their hyperboloid concrete eyries. Meanwhile, if uncertainly, Drax Power Station near Selby, fully fuelled since 2018 by biomass, and with its dozen attendant cooling towers, steams on for now. Perhaps there is hope yet.