This article is taken from the April 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

British farming is a peculiar business. Rarely does one farm enterprise feel they are in direct competition with another. Naturally, discourse and occasional hostility does occur between agrarian neighbours. Altercations over boundaries, straying livestock or even whose bull has the most potent semen are a norm.

Yet on the whole these quarrels are all part and parcel of rural life. When it comes down to the nitty-gritty of business, British farmers largely operate with a mien of collaborative shared endeavour, quite unlike the cut-throat rivalries seen in sectors such as manufacturing, finance or utilities. History helps to explain this happy state of mind.

British farmers being endowed with the spirit of “we’re in this together” is well evidenced. The farming cooperative movement first emerged in the UK, with the Rochdale Pioneers establishing a successful commercial collective in 1844. Dozens more regional agricultural cooperatives were constituted throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, as the nation’s farmers sought to collaboratively address challenges to their businesses. Up until the end of the First World War, ninety per cent of British farmers were tenants rather than landowners in their own right.

The social and economic changes following the Armistice of 1918 were seismic for the British countryside, its economy and balance of power. Many heirs to landed families had lost their lives. Punitive taxes were heaped on estates, accelerating their break-up. The coalition government introduced policies that facilitated land sales and tenant buy-outs.

Lloyd George believed he had smashed the long-standing overweening power of the landed aristocracy. Whilst his suite of targeted taxes guaranteed greater state control over national food security and the land use, it also gave birth to problems for politicians, ones that continue to befuddle them to this day.

The agricultural cooperative model expanded and refined over following generations. Agricultural associations were formed, enabling favourable financial terms through group purchasing and sales, specific sector or regional marketing campaigns for crops and produce. In isolation farmers were minnows, but in alliance they became powerful. The strength of this upwardly mobile new squirearchy inevitably became too much for government to stomach. One farmer does not pitch his grain, vegetables, milk or meat against another’s in the marketplace. The farmer’s primary business rival (aside from the natural forces of unfavourable weather) is not his fellow agrarian, but the government.

Since the post-1918 shift in landownership, successive governments have simultaneously feted farmers in public, whilst hating them in private. This is unsurprising. It is the farmer who owns and controls around 80 per cent of the physical land beneath our feet.

Curbing the strength of farmers — particularly when they join their business together in collaborative agricultural associations — and controlling the quantity and cost of food they grow, is a common challenge for those in power. In dictatorships such as the Soviet Union, North Korea, China or Cuba, the issue was addressed by collectivisation and nationalisation. The result, in all cases, was a decline in productivity, widespread famine and death.

Western democracies chose instead to use more nuanced mechanisms to determine food prices and exert land control. Subsidies, quotas, export restrictions and trade policies were placed on food — largely, if not exclusively, for the benefit of the consumer. Since the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846, the state has de-horned British farmers through the medium of food imports.

Why bother with domestic food security when the British empire was such a cost effective bread-basket, it was reasoned? This strategy remains in place today: despite the loss of our colonial possessions, UK growers continue to compete in a market flooded by cheap imports, particularly from the trading empire known as the EU.

There are now more than 100 farm clusters across England, empowering farmers to claw back control

To counter the challenges from imports, British agriculture swiftly and independently industrialised. Mechanisation, intensification, mono-cropping, reduction in the labour force and a growing reliance on chemical sprays and artificial fertilisers were all inevitable necessities. With domestically grown food reduced to a comparable or lower price point compared with imported produce, both Labour and Conservative governments could reflect that their long-term food and farming strategies had been successful. UK farmers were firmly at heel, food was low cost and the population well fed, fat and largely content. When the UK joined the EU in 1973, the average household spent 31 per cent of their annual income on food and drink. By the time we left in 2020 this had fallen to around 10 per cent. Food had never been cheaper, and our wildlife had never been in a worse state as a result.

The 1980s saw a growing public concern about environmental issues. Influencers placed particular emphasis on the impacts intensive agriculture made on wildlife, habitats and water quality. Whilst there were widespread calls for environmental action on farmland, few campaigners saw fit to admit that biodiversity decline is an inevitable consequence of the rapacious drive for low-cost food. It was far easier for the Green movement to blame the landowners.

Farmers were merely playing the cards dealt by the state. The Thatcher government attempted to address the calls for environmental action by introducing the landmark Environmentally Sensitive Area scheme. This designated specific areas of high environmental value where farmers could enter into agreements to manage their land in ways that would benefit wildlife and the landscape. Farmers received payments for adopting environmentally friendly practices, such as reducing artificial fertiliser and restoring hedgerows.

The ESA was replaced by the Countryside Stewardship Scheme in 1991, broadening the focus beyond designated areas and widening the range of environmental management options. In 2005 Environmental Stewardship was introduced, with different tiers of agreements offering varying levels of environmental management and payments.

The UK’s exit from the EU heralded a more bespoke, and more effective, means of state intervention in agriculture. The Environmental Land Management scheme (ELMs) and the Sustainable Farming Incentive were the masterplan of then DEFRA secretary of state Michael Gove, a policy that the incoming Labour regime declared it would adopt following their victory in the 2024 general election.

ELMs indicated a fundamental shift in government’s (and presumably society’s) expectation of the role the English countryside plays. No longer was a farmer’s primary role to feed the nation. Gone were any direct EU-backed subsidies for domestic food production via payments based on the amount of land owned. Instead, farmers were rewarded for the environmental benefits they delivered.

A principle of “public money for public goods” was applied where taxpayers’ money was employed to support activities that benefitted society as a whole. Admittedly, food production wasn’t wholly sidelined in the Gove concept. Financial rewards were made for reduced fertiliser use, better soil health or removing less fertile land out of cultivation. Minette Batters, the then NFU president, stated, “We need a system that supports farmers in producing food and delivering for the environment. It’s not an either/or situation.”

It became obvious in short order that she and her members had got what they wanted with ELMs. Comments from farmers who enrolled on the scheme were overwhelmingly warm; some were even effusive: “ELMs is the best way for me to farm in a way that’s good for the environment and good for my business. It’s about working with nature, not against it,” one Norfolk farmer commented. “I like it that ELMs isn’t a one-size-fits-all approach. I can choose the options that work best for my farm and my goals,” said another, from Suffolk.

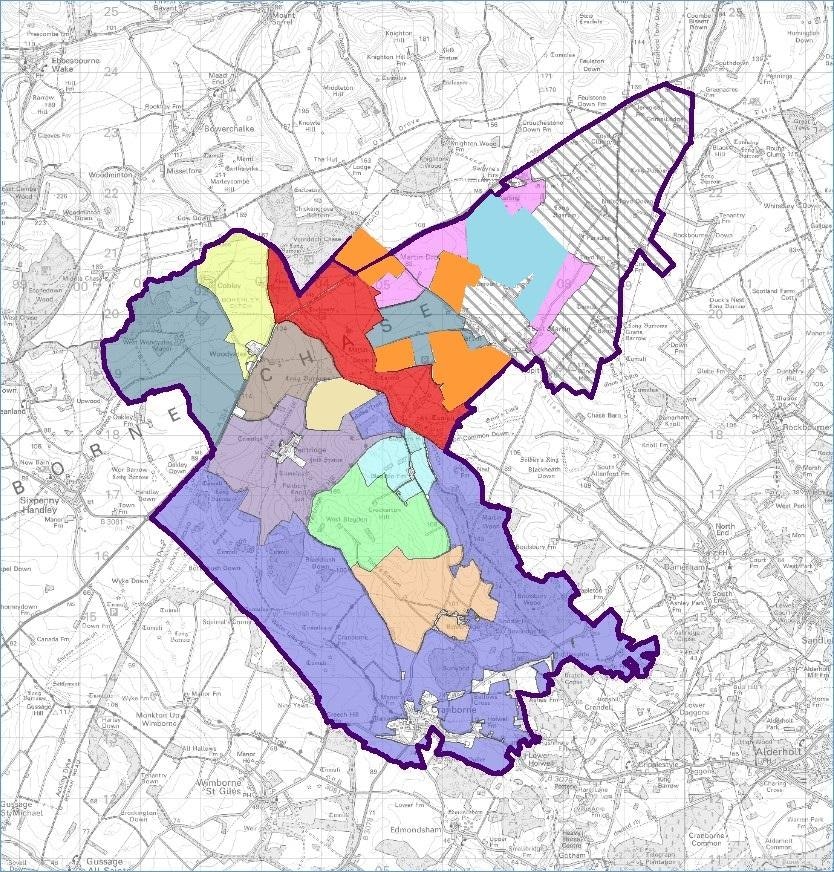

The refocusing of agricultural policy in favour of wildlife conservation and environmental good gave rise to a resurgence in farmer cooperation and joint endeavour. The Game and Wildlife Conservation Trust first mooted the idea of farm clusters in 2012. The Martin Down cluster was formed in 2016, comprising 12 farms and 5,500 hectares in the Cranborne Chase region. There are now more than 100 farm clusters across England, empowering farmers to claw back some control of their own businesses from the state.

Farmers so readily embraced the idea of clusters because they saw that neighbourly cooperation was essential if the benefits of ELMs were to be maximised. This was a win for wildlife, too: nature recovery is only truly possible when practical conservation is undertaken at landscape scale.

Clusters are formed around river catchments or localised soil types. Farm boundaries are invisible to wildlife. Farmer clusters bring to our flora and fauna a cohesive repeating pattern of food and habitat over tens of thousands of hectares. The cost savings, shared resources and pooling of expertise that clusters enable ensure that this a more profitable and sustainable business model.

Indeed, farm economics has transformed since the advent of ELMs and farm clusters. Farmers now increasingly farm to a gross margin rather than simply for yield. Fertile land requiring lower inputs to produce a profitable crop continues to be farmed intensively for food. Lower yielding marginal land, demanding higher, more polluting inputs, is where nature-friendly seed mixes are sown, cover crops drilled, woodlands and hedgerows planted, wetlands dug or floristic meadows created.

Increasingly farm clusters are turning to private enterprise rather than the state to support their environmental deeds. The mutual opportunities are obvious. Environmentally-sensitive farming has attracted the interest and investment of global brands such as Pepsi Co and Nestlé Purina. More environmentally-conscious customers are demanding their breakfast cereals or carbonated drinks have a cleaner, greener footprint. Likewise, sectors such as petrochemical, airlines, automotive, finance and construction are looking to UK farmers to help offset the habitat loss, pollution or carbon emissions caused by their practices.

Critics argue this is an example of “greenwashing”. The yellowhammers nesting in new hedgerows funded by an oil giant or the bees buzzing in a meadow paid for by a City trading conglomerate are ambivalent. Of course, this private investment is better overall for the farmers themselves. For the first time since the repeal of the Corn Laws, UK growers have found a way to bypass the financial shackles created by food imports.

Whilst the food they grow continues to be woefully undervalued, the environmental potential of the land itself has far greater value. Small and medium-sized family farms, operating in collaboration in clusters, have created blocs of landscape scale players in the carbon and biodiversity offsetting markets. This is, or sadly was, a lifesaver for both our nation’s farms and the wildlife that calls these places home.

The current Labour government has plans for farmland that don’t include wildlife, farm clusters or even family farms. Once in power, Labour immediately cut the DEFRA budget in real terms by 1.9 per cent and froze Countryside Stewardship capital grants until at least June 2025, with no guarantee of a thaw. A £358 million underspend in DEFRA during Rishi Sunak’s administration, earmarked for farmer support for nature recovery, will now instead fund flood alleviation for new housebuilding schemes.

Add to this Rachel Reeves’s budget inheritance tax raid on farmland, assets and buildings valued over £1 million, and in the seven months since the general election agricultural communities have been plunged into turmoil. Analysis by the land agents Brown & Co reveals that up to 25 per cent of farmers are contemplating selling up, particularly those with elderly relatives who remain as partners in the business. Speculators in the green energy and housebuilding sectors, including the multi-million-pound Labour donor Dale Vince, owner of Ecotricity, are salivating at the prospect of this weakened state farmers find themselves in.

With farmers on the financial ropes, the Starmer administration is planning a legal change that will enable them to land a winning blow. Fast-tracked changes to the mechanisms of compulsory land purchase are under way. The new legislation will mean farmers are only paid for the miserly “use value” of land rather than its true market value.

This opens a door for a cut-price land grab by the government. Ed Miliband’s vision of swathes of electricity pylons, wind turbines and solar farms sweeping across the shires is no longer a pipe dream. Angela Rayner’s plans for housing estates emerging like mushrooms in a meadow are taking shape.

Any landowner or local resident seeking to check these assaults on farms and nature have been declared enemies of the state — slandered by the Prime Minister as “Blockers” and “NIMBYs”. The long-standing battle between the farmer and the government is reaching its conclusion. The future looks a hungry place to be for man, bird and animal alike.