This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Regardless of whether white Britons cared how black immigrants from British colonies referred to them in 1956, Colin MacInnes was keen to tell them.

Eight years after the Empire Windrush brought that first wave of Caribbean migrants to Tilbury Docks, his essay, “A Short Guide For Jumbles (to the Life of their Coloured Brethren in England)”, revealed that the “Jumble” of the title was a corruption of “John Bull”, used by West Africans to describe Englishmen “in a spirit of tolerant disdain”.

In his eagerness to enlighten the Jumble, the author seemed to be inadvertently confirming certain fallacies, as well as stereotyping both blacks and whites to a risible degree. He wrote: “What most differentiates the African from the Englishman is that our chief ambition is to put our lives into a savings bank, whilst he firmly believes that every day is there to be enjoyed.”

When MacInnes died, aged 61, in 1976, the obituary in the New York Times — a newspaper he contributed to along with British magazines — described him as “one of the first novelists to deal with Britain’s community of blacks”. His contemporaries covered similar territory. The Trinidadian writer Sam Selvon arrived in Britain in 1950 and published his novel The Lonely Londoners six years later. In To Sir With Love (1959), Guyanese-born E.R. Braithwaite fictionalised his experience as a teacher in an East End school.

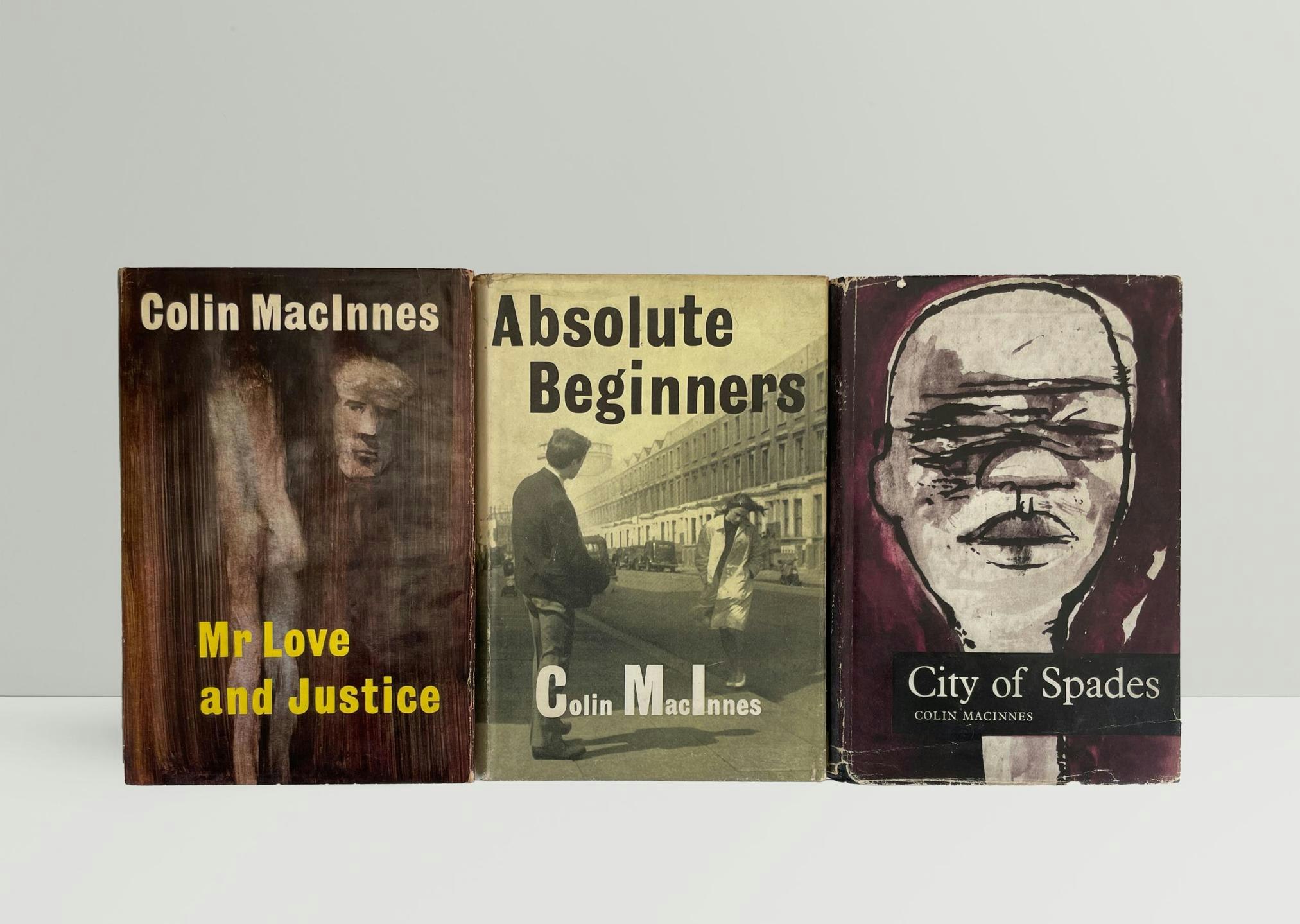

Whilst these black authors were writing as interlopers in their adopted country, Colin MacInnes was a white, well-bred Englishman describing the experience of the black outsider in the trilogy of novels that assured him his legacy: City Of Spades (1957), Absolute Beginners (1959), Mr Love and Justice (1960). The themes common to these books are race, crime, youth and a changing London (a decade before it officially began to “swing”) — topics that still resonate there almost half a century after Colin MacInnes’ death from lung cancer, and 75 years on from the publication of his debut novel, To The Victors The Spoils (1950).

As well as being one of the first authors to write about the black experience in Britain, MacInnes, who was openly bisexual, was one of the first to write rationally on the taboo subject of homosexuality — describing it as “English Queerdom” — before legalisation in 1967. Above all else, he is remembered as the first writer to celebrate the new phenomenon of the “teenager” in the 1950s (even though he was in his forties at the time).

If age made him an odd chronicler of the young, his pedigree made him an unusual candidate to tackle race. He was related to Rudyard Kipling and Stanley Baldwin. His great-grandfather was the artist Edward Burne-Jones. His mother was the novelist Angela Thirkell. Born in England, he spent his childhood in Australia, with a spell in Europe as a teenager before serving in the Intelligence Corps during the Second World War, which provided the inspiration for that first novel.

His social pedigree may have been his entrée to a broadcasting role at the BBC, where he was initially commissioned to write radio scripts whilst embarking on the career as a freelance journalist that kept him afloat in later years, when his novels failed to match the success of the earlier trilogy. The film critic Philip French, a former BBC colleague, described MacInnes as “one of the rudest people I’ve ever met, always needling away to try and expose some bourgeois trait he might, as a good bourgeois, disapprove of”.

The London of MacInnes was notably that of Notting Hill, Fitzrovia and Soho, where he drank to excess with fellow writers and artists at the Colony Room Club. Photographs taken in the 1950s capture him casually attired in grubby bedsits, where he wrote most mornings, before a daily constitutional through Hyde Park.

Notting Hill was infamous for the slum housing that made landlord Peter Rachman notorious and which the narrator in Absolute Beginners (in which the neighbourhood is re-named “Little Napoli”) reflects on, highlighting the “diarrhoea-coloured street lighting”, the “mulligatawny fog” and “broken milk bottles everywhere scattering the cracked asphalt roads like snow”.

The locale was a novelty for “good bourgeois” bohemians like Colin MacInnes but a necessity for the black immigrants that gravitated to the area. By reporting on their experiences, he wasn’t merely documenting the spirit of the times but attempting to expose its injustices. The race riots in Notting Hill in 1958 had a major impact on him and to the close of Absolute Beginners.

MacInnes wrote numerous essays on race, beyond his guide for white natives on black immigrants. In “Britain’s Mixed Half-Million” (1961), he sought to further enlighten the Jumble. According to MacInnes, West Indians arrived to escape overpopulated islands in pursuit of prosperity, whilst West African men were seamen, traders or students propelled by wanderlust. He writes: “It is only exceptionally that one may find Africans in England who decided to emigrate because of extreme economic hardship in their homeland.”

Whilst northern working-class writers were producing accounts of their native experience in novels, films and the cinéma-vérité drama that was dominant at the BBC by the 1960s, the London working-class experience was cornered by upper-class interlopers. In 1965, Nell Dunn’s novel Up The Junction became the BBC “Wednesday Play”. Her husband, Jeremy Sandford, wrote the infamous BBC screenplay Cathy Come Home the following year.

MacInnes had been attempting something similar the previous decade, but, despite the gritty subject matter and social issues central to his output, the novels were in the realm of fantasy. In these stories the characters, with names such as “Johnny Fortune”, “Frankie Love” and “Crepe Suzette”, are shorthand for the youth gangs or ethnic and social group they are part of, complete with exaggerated slang dialogue, rather than realised naturalistic figures.

MacInnes writes about black figures in a manner that would be impossible for a white author in the current climate of territorial identity politics, even though his approach is positive and his intention honourable, whilst the topicality of the issues he addressed — immigration, sexuality, racism, post-colonialism, vice — blinds those readers persuaded by his leftish viewpoint to the fancifulness of the style.

Even MacInnes was quick to dismiss any suggestion that his novels were the result of forensic and exhaustive research, referring to them as “poetic evocations of a human situation”.

The white adults he wrote about sometimes fitted the petit bourgeois stereotype he abhorred. This is evident in his essay “The Express Families” about the characters that appeared in the Giles cartoons in the Daily Express. Like George Orwell’s take on “Boys’ Weeklies” from 1940, this suited the cultural studies territory MacInnes was treading, along with academics Richard Hoggart, Raymond Williams and Stuart Hall, whilst contributing to high end literary magazines such as Encounter.

His biographer Tony Gould, who commissioned him when he was literary editor at the New Statesman, has suggested that, like Orwell, MacInnes is a better essayist than novelist. His journalism took him beyond the West End postcodes with which he was familiar, in essays entitled “Hamlet and the Ghetto” or “The Pied Piper of Bermondsey”, a profile of the local boy made good, Tommy Steele.

But as with the readers of the Daily Express, the teenagers embracing the new consumerism were also subjected to his criticism because of their indifference to politics: “in their kind of happy mindfulness — the raw material for crypto-fascism of the worst kind”.

Although MacInnes occasionally concedes that the good, the bad and the ugly are to be found in all races, his tendency is to deify the black foreigner and demonise the white native. In this, he’s emblematic of white writers from his class and with his politics and pedigree that have continued to mine the same territory and re-enact battles already won, in a world that has moved on since those days of the diminishing British Empire.

In part, his portrayal of black characters was based on his objectification of them, and particularly African men, to whom he was especially sexually attracted. He pursued them, often conquered them, usually by offering cash, before discarding them.

In his 55-page pamphlet “Loving Them Both” (1973), a study on bisexuality, he outlines how same-sex attraction plays out amongst black men in foreign climes, highlighting where it is most prevalent: “the virtue of anyone who, in Barbados, bends to retrieve a coin, is in dire danger”.

Here again in attempting to expose the assumptions of others, he reveals his own. The black man is cast as carefree and exotic, a sexual radical with a natural sense of rhythm (“blacks regard a bed as a place of joy and not a confessional”). He is invariably a musician, a pimp, a hustler who, of course, avoids putting his life in savings banks because every day is there to be enjoyed.

Just as MacInnes had little interest in a white working class that might aspire to the status of those Express families, let alone the class of which he was a beneficiary, the educated black man did not hold his interest — unless, of course, he was a revolutionary.

Colin MacInnes became the token white figure to the fore of short-lived black liberation groups that limped into the London of the 1970s and landed on the agitprop pages of listings magazines. He was a propagandist for black “revolutionary” and convicted murderer Michael X, who was executed in his native Trinidad in 1975. In his final years, MacInnes’ focus on race was surpassed by sexuality, which he wrote about under a pseudonym in a column for Gay News: “Captain Jockstrap’s Diary”.

He died on the Kent coast and was buried at sea, far from his beloved London. Half a century on, the capital is a city he would barely recognise — not because of the regeneration and gentrification but the mass immigration that has followed in his wake.

For certain Londoners that remain, London is a foreign city; for those that have left, it’s an alien one. The diarrhoea-coloured street lighting and mulligatawny fogs that were the backdrop to the lives of MacInnes and his characters, that once made it a dark and dismal city, have gone. But so have many of the attributes that made it a safe, sane and dignified one.