China is preparing to dramatically scale up forced organ donations from Uyghur Muslims and other persecuted minorities, rights groups have claimed.

A statement published in December 2024 by China’s National Health Commission announced plans to triple the number of medical facilities capable of performing organ transplants in the Xinjiang region, home to the vast majority of Uyghurs in the country.

Six new transplant institutions are due to be built by the end of the decade, bringing the region’s total to nine, according to the Plan for the Establishment of Human Organ Transplant Hospitals in Xinjiang Uygur Autonomous Region (2024–2030), issued by Chinese authorities.

The expanded facilities will reportedly be authorised to perform transplants of all major organs, including hearts, lungs, livers, kidneys and pancreas.

But official figures show Xinjiang’s voluntary organ donation rate stands at just 0.69 donors per million people – less than one-sixth of the national average of 4.6.

The move has prompted warnings from rights campaigners and international human rights experts who say the planned expansion aims to fuel industrial-scale organ harvesting from prisoners of conscience.

‘This massive expansion in Xinjiang, a region already under scrutiny for systematic repression, raises deeply troubling questions about where the organs will come from,’ said Professor Wendy Rogers, Chair of the Advisory Board at the International Coalition to End Transplant Abuse in China (ETAC).

‘There is simply no justification for such growth in transplant capacity given the region’s official organ donation rate, which is far below the national average.’

Beijing has repeatedly denied accusations by human rights researchers and scholars that it forcibly takes organs from prisoners of conscience.

A medical facility in Urumqi, captial of Xinjiang province, is seen in this image

Cheng Pei Ming, a victim of forced organ donation displays his scars after escaping China

When he refused to sign surgery consent forms Cheng was immediately tackled by police officers and injected with a tranquilliser

This photo taken on June 2, 2019 shows buildings at the Artux City Vocational Skills Education Training Service Center, believed to be a re-education camp where mostly Muslim ethnic minorities are detained, north of Kashgar in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region

The planned expansion outlined by the National Health Commission includes facilities across northern, southern and eastern Xinjiang, including in the capital Urumqi.

Of the nine total hospitals set to be operational by 2030, seven will perform heart transplants, five will offer lung transplants, four will carry out liver operations, and five will conduct kidney and pancreas procedures.

Critics say this network will far outpace the needs of the region’s population, suggesting that the only reasonable explanation is that authorities are planning to forcibly harvest organs from detainees.

It is estimated that between 60,000 and 100,000 transplants are conducted in China each year – vastly more than the country’s official donation system can support.

Since 2006, practitioners of the Buddhist practice of Falun Gong have been the primary victim group of forced organ harvesting, with the Uyghur population now thought to be at risk.

MailOnline previously covered the nightmarish story of Cheng Pei Ming, a rural villager and Falun Gong practitioner from China’s Shandong Province, who endured unimaginable suffering from forced organ transplants before eventually escaping and making his way to the United States.

Although China claimed in 2015 to have ceased using organs from executed prisoners, no legal reforms accompanied the announcement, and harvesting organs from prisoners of conscience was never explicitly outlawed.

Meanwhile, Uyghur Muslims held in Chinese detention camps have reported undergoing blood tests, ultrasounds and other organ-focused medical scans, procedures consistent with assessing organ compatibility.

‘The concept of informed, voluntary consent is meaningless in Xinjiang’s carceral environment,’ said David Matas, a veteran human rights lawyer and Nobel Peace Prize nominee who has investigated forced organ harvesting in China for nearly two decades.

‘Given the systemic repression, any claim that donations are voluntary should be treated with the utmost scepticism.

‘The lack of legal safeguards, the history of abuse, and the ongoing repression in Xinjiang all point to the urgent need for independent scrutiny of this transplant expansion,’ added Dr Maya Mitalipova, a geneticist who has testified before the US Congress about reverse organ matching techniques and biometric surveillance in China.

‘This could be industrial-scale organ harvesting under a state-controlled system.’

The United Nations and several democratic governments have repeatedly voiced concern over credible reports of forced organ harvesting and systemic repression of Uyghurs, Falun Gong practitioners, and other minority groups in China.

In June 2021, 12 UN special rapporteurs and human rights experts raised the alarm over allegations that minorities in Chinese detention were subjected to blood tests and organ scans without consent.

Their findings suggested that results were entered into a national database used to allocate organs.

Cheng awoke to find a huge incision down the side of his chest leaking fluid

Images of Cheng shackled to a hospital bed emerged on a website dedicated to publishing news on the persecution of Falun Gong practitioners

IV lines are seen snaking into Cheng’s body following his forced surgery in 2004

A person holds up a placard during a protest by at least 28 diasporic groups – including Hong Kong, Tibetan, Uyghur, Chinese Dissident, and other resident organisations – outside the proposed site of the new Chinese Embassy redevelopment in Royal Mint Court central London

Recent political momentum in the US has seen a flurry of legislative action, including the introduction of the ‘Falun Gong Protection Act’ in March 2025, and the passing of the ‘Stop Forced Organ Harvesting Act’ in the House in May.

State-level legislation banning collaboration with Chinese transplant institutions has also been adopted in Arizona, Texas, Utah, Idaho and Tennessee.

Campaigners now want the international community to pressure Beijing for full transparency over the Xinjiang expansion plans.

Those subjected to forced organ harvesting endure horrific treatment and are slowly deprived of life piece by piece.

The depravity of the practice was unmasked last year by Falun Gong practitioner Cheng, who spent several years incarcerated and forcibly donated parts of several of his organs.

Between 1999 and 2006, he faced relentless persecution for his religious and spiritual beliefs by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and endured several periods of detention during which he is believed to have been repeatedly tortured.

In one of the most chilling episodes of his captivity, Cheng was taken to a hospital where doctors pressured him into signing consent forms for surgery.

When he refused, he was immediately injected with an unknown substance, which knocked him out.

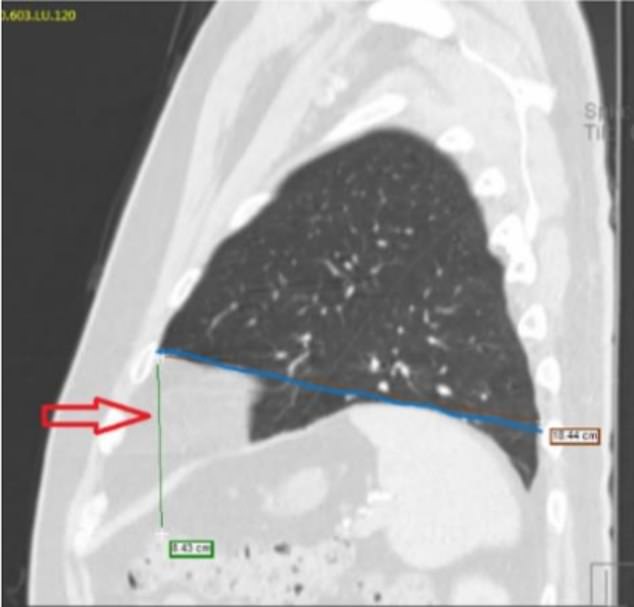

He awoke with a massive incision down the left side of his chest, and scans have since confirmed that segments of Cheng’s liver and lung had been removed.

While Cheng lay in bed, photos depicting the aftermath of his forced surgery were taken and sent to Minghui.org – a website sharing information on Falun Gong that also publishes news about the persecution of its practitioners.

Cheng is clearly seen unconscious and chained to the bed in the images, which he suspects were taken by a shocked nurse or hospital worker.

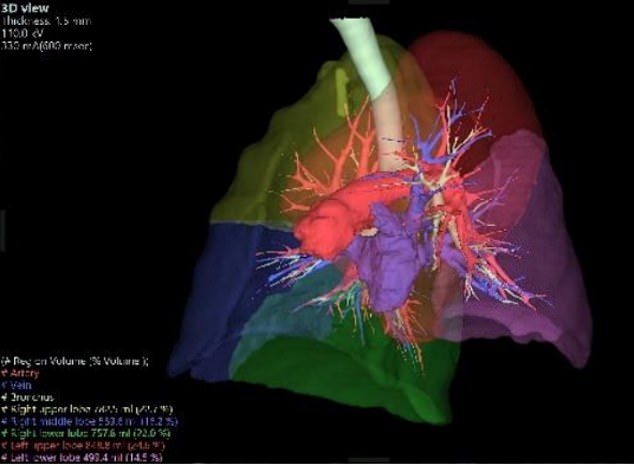

Subsequent medical examinations conducted in the US confirmed that segments two and three of Cheng’s left liver lobe and half of the left lower lobe of his lung were missing.

The removal of liver segments aligns with a technique developed in the 1990s for paediatric liver transplants, prompting experts to conclude Cheng was used as an unwilling organ donor – as well as highly unethical medical experimentation.

Cheng’s shackles are seen on his hospital bed hours after he was operated on in China

About half of Cheng’s lower left lung lobe is missing

This 3D reconstruction of Cheng’s CT scan shows a considerable chunk missing from one of his lungs

In March 2006, after initiating a hunger strike, Cheng was hospitalised again – but this time he claims he was told he’d have to undergo another unspecified surgery, even though he had not ingested any foreign objects.

Realising he was about to face another brutal surgery and almost certain death, he staged a daring escape.

Hours before his operation was due to be performed, he asked the guard monitoring his room overnight to take him to the toilet. Upon returning to the room, Cheng said the guard forgot to shackle him to the bedframe, and a short while later, fell asleep in his chair.

Cheng seized the golden opportunity, sneaking out of the room before fleeing via the hospital’s internal fire stairs and flagging down a taxi.

That escape marked the beginning of a long journey to freedom that took Cheng across international borders and through countless challenges on a 14-year campaign to avoid the Chinese authorities.

After nine years on the run in his native land, he managed to flee the country and settle in Thailand, where he spent another five years looking over his shoulder until he was eventually granted UN refugee status.

In July 2020, Cheng completed his bid for freedom when he landed safely in the United States, where he now acts as an advocate for ETAC.