For once, Edie Sedgwick, socialite, party-loving It girl and Andy Warhol’s legendary muse wasn’t having fun.

Inebriated and in her underwear, playing a version of herself in the artist’s 1965 avantgarde film, Beauty No. 2, the 21-year-old seemed to be vulnerability personified.

The set was a rumpled bed; her co-star, 21-year-old American actor Gino Piserchio and the ‘plot’ for what it’s worth involves the pair romping while two voices off camera taunt her to get a reaction.

‘You’re not doing anything for me yet Edie.’

‘You can do better than that… That boy’s not here for the fun of it.’

Then, the real stinger: a reference to Sedgewick’s childhood sexual abuse at the hands of her father.

She throws an ashtray in frustration. She’s not acting.

Bullying and exploitative, it’s the darker side of Warhol whose artwork blazed in vivid technicolor from the mid-20th Century and remains in high demand. (One of his lesser known paintings, Flowers, sold for just shy of $35,500,000 at Christie’s New York this year.)

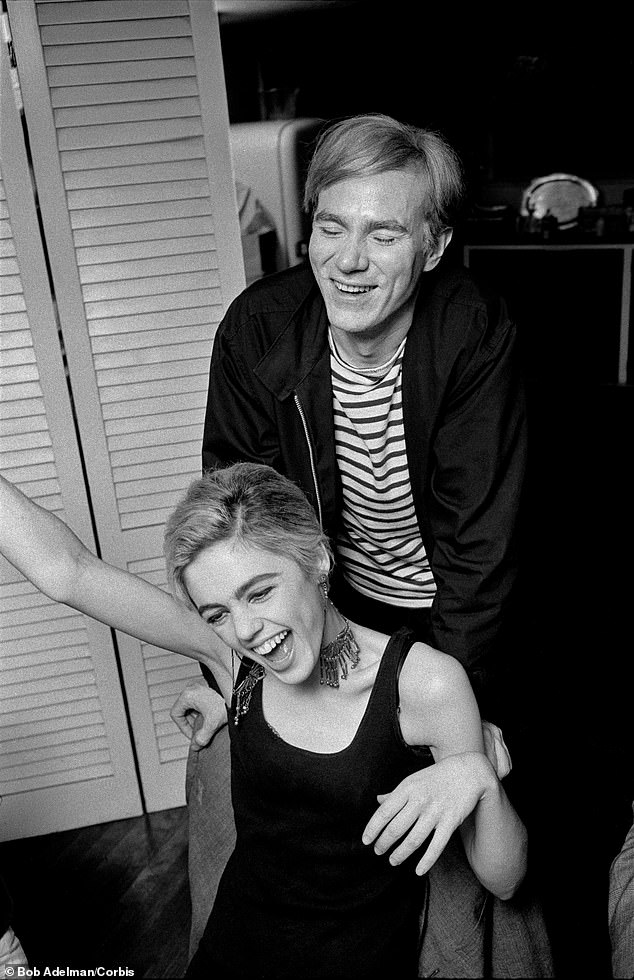

For once, Edie Sedgwick (pictured), socialite, party-loving It-girl and Andy Warhol’s legendary muse wasn’t having fun

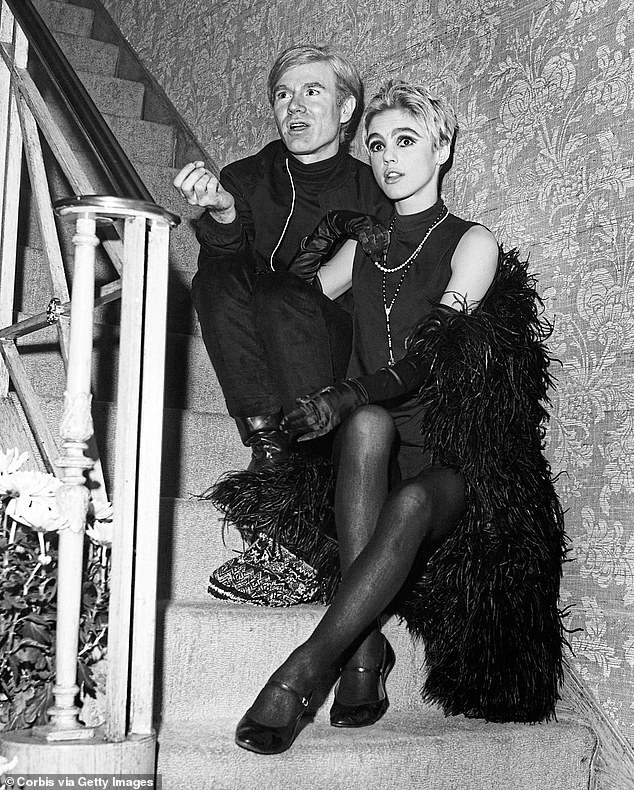

Bullying and exploitative, it’s the darker side of Warhol whose artwork blazed in vivid technicolor from the mid-20th Century and remains in high demand (Pictured: Warhol and Sedgwick)

Sedgwick, meanwhile, would be chewed up and spat out, dying from a barbiturates overdose at just 28 while Warhol moved onto the next bright young thing.

While the pop art pioneer elevated Campbells soup cans, Coke bottles and Brillo pads to fine art on canvas, it was behind the camera lens that his perversions unfolded in an explosion of sado-machoism, cruel emotional abuse and crude casting calls.

For the master and his muse who met 60 years ago at American film, TV and theater producer Lester Persky’s party – the soiree was thrown for writer Tennessee Williams’ birthday – the line between inspiration and exploitation remained a fine one.

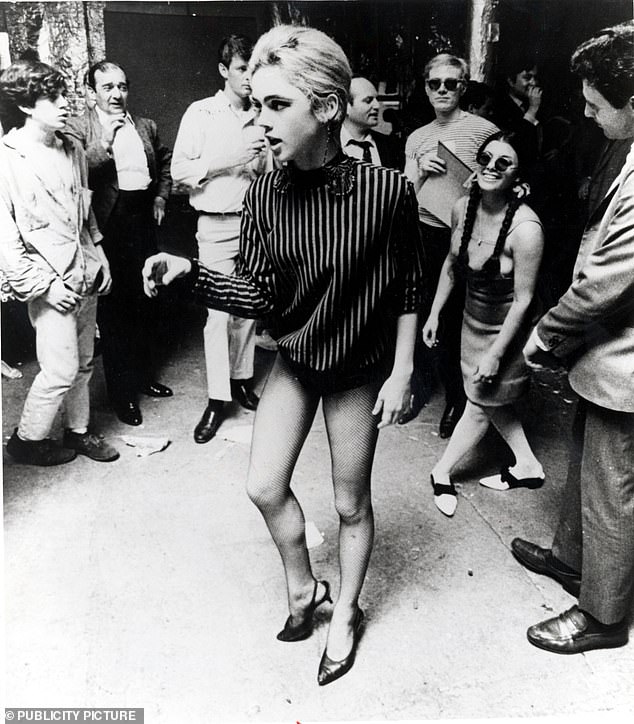

It all played out at his midtown Manhattan studio known as the Factory in a haze of sex, drugs and art in the mid to late ’60s, where young and attractive art groupies keen to appear in Warhol’s underground films would indulge his creative whims and kinks.

Take Gerard Malanga. As a 21-year-old assistant he was paid the minimum wage (then $1.25 an hour) to assist Warhol with printing but the role would soon expand – and see him donning a bondage mask in the film, Vinyl, Warhol’s homoerotic and fetishistic adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel A Clockwork Orange.

‘Andy was a voyeur – he loved watching others engaged in sexual activity, loved controversy and stirring things up,’ art dealer and Warhol expert Richard Polsky told the Daily Mail.

‘Surrounding himself with young attractive people made him feel better about himself; he knew he was a great artist, but he had insecurities about his appearance; he liked the fact their glamour rubbed off on him.’

As it did with Sedgwick. The aspiring model and actress from a prominent society family in Santa Barbara was hungry for a hedonistic escape when she collided with 37-year-old Warhol and became his leading lady and a platonic arm candy.

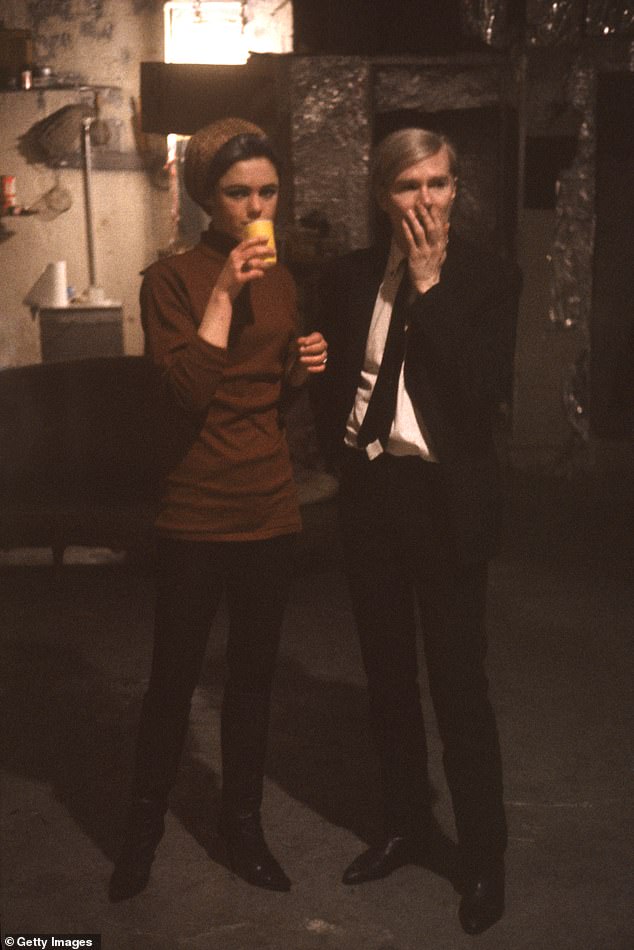

It all played out at Warhol’s midtown Manhatton studio known as the Factory in a haze of sex, drugs and art in the mid to late ’60s (Pictured: Warhol photographed at the Factory)

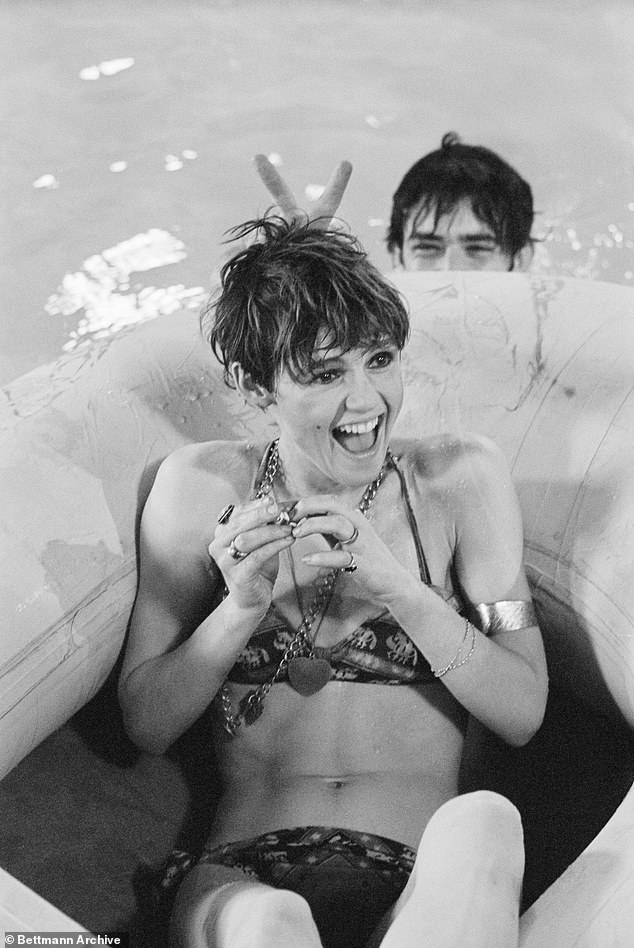

Sedgwick (pictured) would be chewed up and spat out, dying from a barbiturates overdose at just 28 while Warhol moved onto the next bright young thing

Her kohl-eyed sultry stare and gamine glamour came with a troubled and tragic backstory: A long-standing eating disorder, she had been committed to psychiatric institutions in Connecticut and New York in 1962. Her two brothers – Francis Jr (Minty) and Robert (Bobby) both died by suicide within 18 months of each other and her manic-depressive and womanizing father, Francis, abused her.

She claimed that her father made his first pass at her she was seven years old. As a teenager, she told people, she happened on her father while he was having sex with a mistress.

In response to being discovered, she says, her father slapped her and called a doctor to give her tranquilizers.

She suffered from bulimia and anorexia.

At 20, she had an abortion.

It was all catnip to creative and controlling minds like Warhol, which loved to exploit the weaknesses and vulnerabilities of the potential ‘superstars’ he worked with.

‘I could see that she had more problems than anybody I’d ever met,’ recalls the artist of his initial impression of Sedgwick in his 1975 book, The Philosophy of Andy Warhol. ‘So beautiful but so sick. I was really intrigued.’

Sedgwick was malleable and useful to Warhol. Her high society connections meant introductions to new and rich clientele, and her rising status was amplifying the fame he always craved.

Her charm and outward confidence made her the perfect foil for Warhol’s awkward pretensions, famously acting as his mouthpiece during a 1965 appearance on The Merv Griffin Show in which the artist refused to utter more than a few words.

‘He’s not used to making really public appearances,’ Sedgwick told a dubious Griffin. ‘He’ll whisper answers to me when you ask him a question.’

Sedgwick’s kohl-eyed sultry stare and gamine glamour came with a troubled and tragic backstory (Pictured: Sedgwick in a scene of Warhol’s Ciao! Manhattan which was released a year after Sedgwick’s death)

Her charm and outward confidence made her the perfect foil for Warhol’s awkward pretensions (Pictured: Warhol and Sedgwick at a Vidal Sassoon party in 1965)

And how was Sedgwick repaid? Well, not with anything approaching a dime.

As much a businessman as an artist, the man who could be reluctant to pay those he worked with had a net worth equal to $220 million at the time of his death at 58 following complications after gallbladder surgery.

But for Warhol, it seemed the cache of being in his orbit was enough to secure free acting talent along with empty promises of a springboard to Hollywood that never materialized.

Sedgwick would star in Poor Little Rich Girl, a film that is little more than a vehicle to mock her vacuous, lifestyle, as she chains smokes, tries on fur coats and lolls around in underwear arranging dates.

But it’s Beauty No. 2 that remains the most disturbing. A drunk, deeply-troubled young women rambling incoherently about her fear of death being mocked and manipulated by the off-camera comments of Warhol collaborator Chuck Wein.

While her male co-star, Piserchio, escaped much comment or criticism, Sedgwick was fair game for the cheap sexual thrills and laughs – instructed to ‘taste his brown sweat’ as the digs flow on everything from her drug dependency, past traumas and even her voice.

‘If you’re not enjoying it, just stop,’ booms the final passive aggressive barb.

Finally, she did.

Phased out from the Factory by 1966 after finally questioning her treatment, Sedgwick was soon on a self-destructive path via a rumored fling with Bob Dylan.

Needless to say, Warhol took great delight in informing her that Dylan had secretly married his girlfriend Sara Lownds having reportedly heard about it through his lawyer.

Sedgwick’s health and fortune declined as her drug use ramped up – something she would blame on the Factory scene – before her untimely death in 1971.

Art historians agree Warhol could have done more to help her, but it seemed his loyalty and true affection just didn’t run that deep summed up by a dismissive eulogy in his book: ‘She was a wonderful, beautiful blank.’

And in the Factory, the production line rumbled on. Warhol had a new muse, Susan Hoffman – who he renamed Viva – another high society beauty he liked to see distressed and undressed. Her starring role in his satirical western movie, Lone Cowboy, sees her character often nude and fending off a gang rape by a group of cowboys.

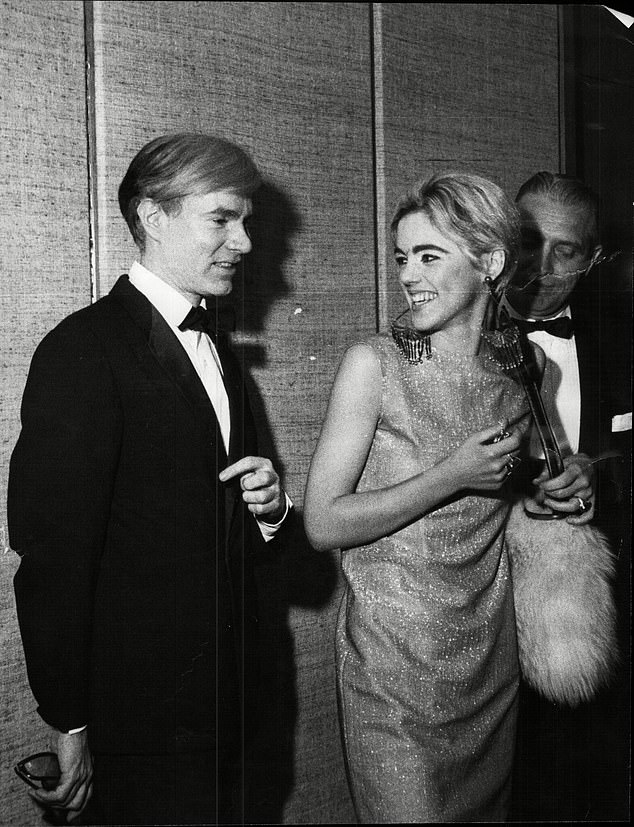

Warhol’s loyalty and true affection just didn’t run that deep, summed up by a dismissive eulogy in his book: ‘She was a wonderful, beautiful blank’

Sedgwick’s health and fortune declined as her drug use ramped up – something she would blame on the Factory scene – before her untimely death in 1971 (Pictured: Sedgwick and Warhol in the Factory in 1967)

Her ‘audition’ when she first approached Warhol to ask if she could be in his next film would a fast track to cancellation in today’s more accountable culture.

‘Andy said: “If you want to take off your blouse, you can make a movie tomorrow,”‘ recalls Hoffman in Jean Stein’s biography, Edie, American-Girl.

‘”If you don’t want to take it off, you can make another one.” I was afraid if I didn’t take off my blouse that very next day he would forget me completely. So, I put these round Band-Aids on my nipples and took off my blouse,’ she said.

Warhol, the mysterious master of passive power; seemed to get away with quite a lot among the impressionable hangers on in his thrall.

In 2022, Warhol’s Shot Sage Blue Marilyn made $195 million at Christie’s in New York – a record for a 20th century work of art, confirming an enduring appeal unscathed by a complex legacy. Yet for a pioneer and progressive who redefined what art is and shaped celebrity culture as we know it, his sexist and regressive abuse of his muse remains a blot on his canvas.

Ultimately for Warhol, a troubled young woman like Sedgwick was as disposable as a can of soup.