This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Dinosaurs seeking to hoard rights: that’s how the foreign secretary, David Lammy, once characterised women who think being a woman is a matter of biology, not identity. Lammy is not one of Nature’s clearest thinkers — he has also said that men who identify as women can acquire a cervix after “various procedures and hormone treatment and all the rest of it”. But his dinosaur dig, however accidentally, neatly encapsulated a usually unspoken left-wing theory: that the left can win the culture wars by out-surviving its opponents.

The thinking is that culture wars are long wars, won not by changing hearts and minds but by waiting until the hearts and minds that disagree with you have stopped beating and thinking. To misquote Martin Luther King, the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends towards your enemies going extinct.

A cunning plan, to be sure, but what if people become more right-wing as they age? They certainly become more realistic, or perhaps more cynical, and it’s received wisdom that this means moving rightward. In a phrase often attributed to Winston Churchill or Bertrand Russell but probably first uttered by Otto von Bismarck: “He who is not a socialist at 19 has no heart. He who is still a socialist at 30 has no brain.”

When it comes to social rather than fiscal policies, however, positions adopted on the threshold of adulthood often last for life. During the 20th and early 21st century, a succession of major shifts across the Western world, including acceptance of mixed-race and same-sex marriage, mothers working outside the home and legal abortion, happened largely as a result of generational turnover. Positions initially held largely by young people marched steadily upwards through older and older age bands with each cohort.

◉ ◉ ◉

What, then, of the dinosaurs who think men can’t be women? The Supreme Court’s ruling in April in the case of For Women Scotland suggests that rumours of our extinction are greatly exaggerated. Its logic means that legal falsification of sex via a gender recognition certificate takes effect only for bureaucratic purposes, and not in situations where that falsification would seriously harm other people’s rights or make other laws inoperable or incoherent.

In other words, “yes” to being allowed to falsify your sex for the purpose of tax returns and pension records; “no” for the purpose of single sex spaces, services and sports.

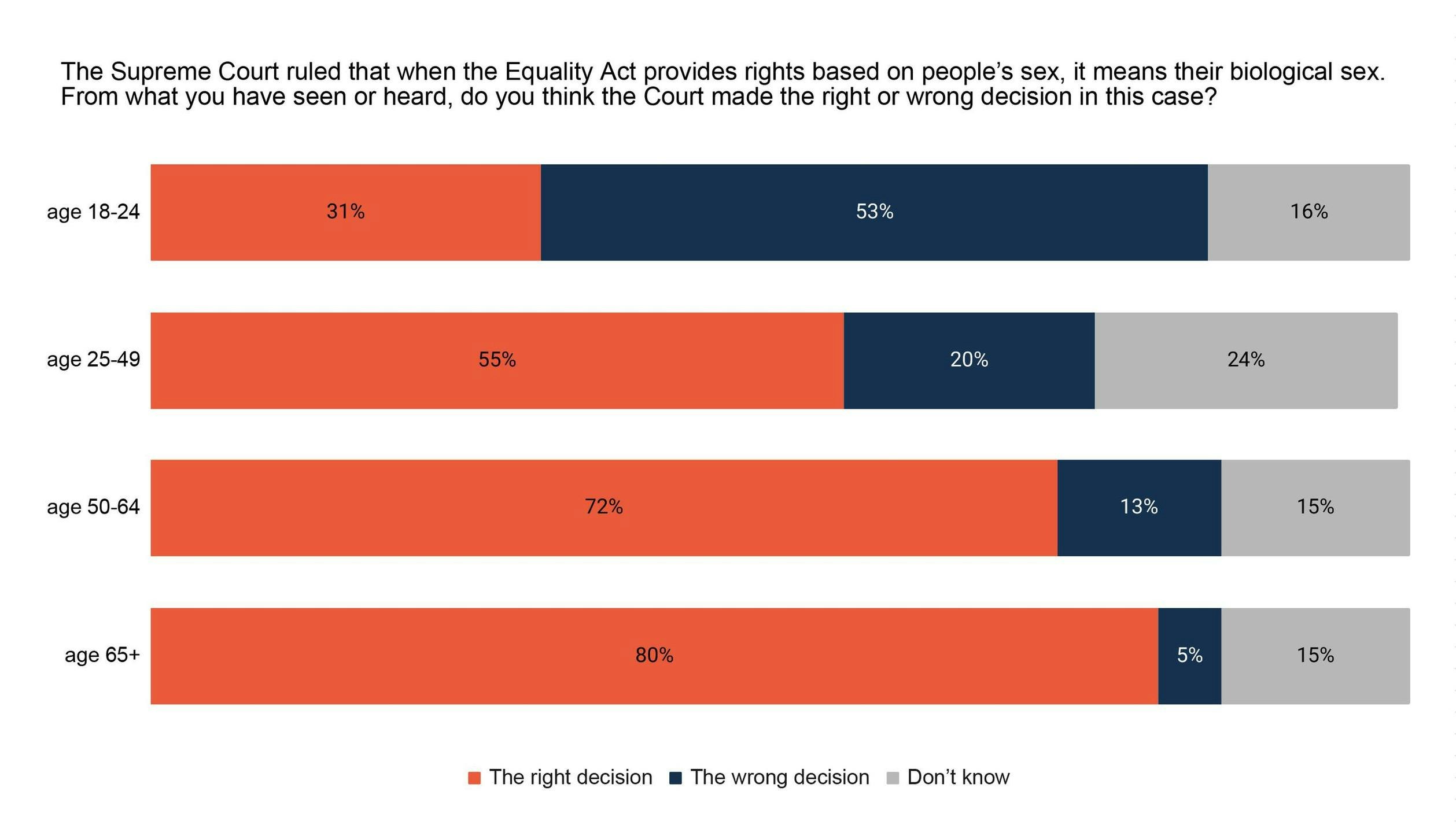

The judgment was extremely popular — except amongst newly minted adults. YouGov polling commissioned by Sex Matters, the human rights charity I work for, found 63 per cent of all adults thought it was the right decision. Just 18 per cent thought it was wrong. But amongst 18–24 year olds those proportions were almost reversed, with just 31 per cent supporting the decision and 53 per cent opposed.

Suppose this pattern persists. Suppose that each generation is keener than the previous one on legal sex change, and that support proves durable as people age. Then the Supreme Court judgment would be nothing more than a temporary stay of extinction.

Every country that has replaced biological sex with self-declared gender identity in law has done so as a result of backroom lobbying, without public support or even awareness. All the Supreme Court would have done is delay things in the UK until public opinion had time to catch up with the activist avant garde.

◉ ◉ ◉

Fortunately for those who care about women’s rights and evidence-based policymaking, support for the trans movement seems to be far more superficial than it was for the previous liberation movements it claims as forerunners.

Since 2018, when YouGov started polling about trans issues, voters of every age have shifted strongly away from all the policies promoted by trans activists, from allowing men to self-ID into women’s spaces and sports to blocking gender-distressed children’s puberty. So marked is this shift that it is swamping the effect of more trans-positive cohorts ageing. The dinosaurs, far from going extinct, are multiplying.

To illustrate with just one of YouGov’s questions, in 2018 two-fifths of all respondents thought men who identify as women should be allowed to use women’s changing rooms, slightly more than disagreed (the rest were undecided or didn’t answer). Now three-fifths say they shouldn’t be allowed, and just a fifth that they should. Amongst 18–24 year olds, three-fifths started out in favour, with just a fifth against. Now this age group is evenly split, with two-fifths both for and against.

Part of the reason supporters are falling away is surely that the more familiar people are with trans activism, the less they like it. But equally important may be the fact that this is the first social movement of the internet age.

Those 18–24 year olds are digital natives, holding many opinions they picked up in parts of the virtual world where almost everyone is young: on subreddits, Discord servers, in-game chats and fan-fiction websites; on Tumblr before it fell out of fashion, and now Snapchat and TikTok. For the first time in human history, much of the socialisation of young people is happening without their elders present, or even aware of what they are learning.

It is both the charm and the weakness of young people to be intellectually and emotionally mercurial. They are inventive and original, but also quick to copy their peers. Without their elders around, they are prone to entering feedback loops that may spiral off in odd, sometimes harmful, directions.

One sign of this is that social media has become a vector for once-rare mental and physical conditions. The craze for identifying as trans is just one example. Others include multiple personality disorder; functional movement disorder (“ticcing”); and postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, or pots — a tendency to severe dizziness upon standing that is the reason increasing numbers of young people on omnicause protests now sport walking sticks.

Even as young people are bringing each other up in the virtual world, responsibility for them is changing hands in the real world, too. Until recently, young people imbibed their ideas and attitudes from older parents, relatives and neighbours, and in churches and social clubs.

But as more women work outside the home, and young people stay in education longer, the job of forming young people’s minds is being handed over from their families and communities to education professionals.

Parents and employers want their children shaped into competent, mentally healthy adults well-equipped to be good spouses, parents and employees. Fine, upstanding adults, in other words. But teachers and lecturers are increasingly trained to see their jobs as something different: to further a certain vision of social justice and to help young people discover their true selves.

In this vision, the young person’s mission is to be a scourge to the oppressor and a comfort to the oppressed. Identity is largely about which groups you belong to — which race, sexuality, gender identity and so on. Everything wrong with your life can be explained by oppression; whenever you’re in an oppressor group you must seek (but never succeed) to atone by being an ally.

The aim seems to be to create lifelong activists agitating for permanent revolution. Far from parents having primary responsibility for educating their children, it’s supposed to be the children’s job to educate their parents.

When opinions were formed gradually and organically within families and communities, it was hardly surprising they were durable. But there’s no reason to think that the febrile notions shared amongst young people online, or the top-down edicts of school teachers and university lecturers, will take such deep root.

◉ ◉ ◉

One pleasing implication is that the recent huge increase in trans identification amongst young people may be about to go into reverse.

A decade ago, children adopting the trans label were setting rather than following a trend; now every classroom has a few they/thems. Any cause that obsesses not only the generation directly above yours, but your teachers, cannot possibly be aspirational.

But the implications go well beyond the trans issue. As identity formation moves from families and communities into online spaces and educational institutions, we may be witnessing an epoch-defining shift as significant as the Industrial Revolution, when production moved from homes to factories. The resulting identities may be better understood as avatars, not merely superficial but temporary; and the ideologies as fashions, about which the only certainty is that they will change.