Yvette Moyo knows what it’s like to live where she’s not wanted. Her family moved into the Chicago neighborhood of South Shore in 1964, a time when an influx of Black families was meeting resistance from the white residents who had long dominated the community. She recalls stern warnings to avoid white-only areas, like the nearby Lake Michigan beach. She remembers when her brother got his nose busted in a city park.

And so last month, when hundreds of masked and armed federal agents stormed an apartment building not far from where she lives, Ms. Moyo felt the weight of history. With a Black Hawk helicopter thumping overhead, agents dragged residents out into the late September night, among them scores of Venezuelan migrants, but also Black U.S. citizens.

“There is a sense of identification with the people who are in our neighborhood and are experiencing some trauma because people do not want them there,” she says. “That is something I definitely understand.”

Why We Wrote This

Chicago residents are grappling with “Operation Midway Blitz,” an aggressive federal immigration enforcement campaign. A major apartment raid in South Shore, a historically Black neighborhood, surfaced empathy and lingering resentment over city support for migrants.

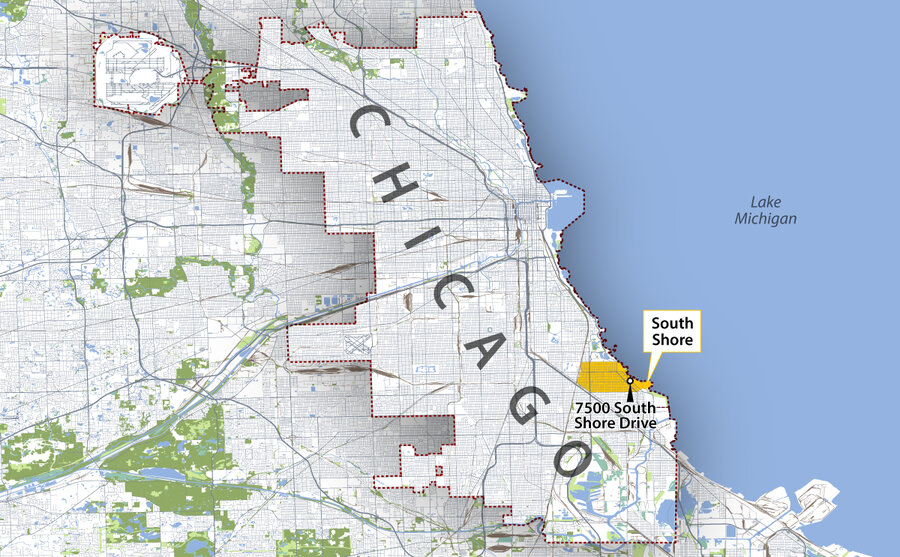

The raid in Chicago’s South Shore neighborhood, during which federal agents detained 37 migrants, was the biggest and most widely publicized action yet in what the Trump administration has dubbed “Operation Midway Blitz.” The U.S. Department of Homeland Security launched the campaign in early September to arrest “criminal illegal aliens” in and around Chicago. But the department’s tactics, including the use of tear gas on protesters, the detention of U.S. citizens, and the fatal shooting of an unauthorized immigrant, have drawn angry protests, legal challenges, and sharp opposition from local political leaders. On Tuesday, a federal judge ordered Gregory Bovino, a senior Border Patrol official leading the immigration crackdown in Chicago, to wear a body camera and provide daily incident reports. The order was paused Wednesday by a federal appeals court.

Within South Shore, the mostly Black neighborhood that hugs Lake Michigan, the apartment raid threw into sharp relief the mixed and often complicated views of the migrants that poured into Chicago starting in 2022. Over 51,000 people “seeking asylum” arrived between 2022 and 2024, according to the city, including 30,000 that Texas Gov. Greg Abbott’s office says he bused there. The influx overwhelmed Chicago, which struggled to house them. It also angered many Black residents, who felt that the city was spending precious resources on the new arrivals while overlooking unmet needs in their communities, many of them struggling with poverty, crime, and high rates of incarceration. These and other concerns still resonate in South Shore.

Ten months into President Donald Trump’s immigration crackdown, polls suggest that a majority of voters back strong border control and favor deporting people who are in the United States illegally. At the same time, most Americans want to see a path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants who are law-abiding and have lived in the country a long time. And approval is fraying for the kind of aggressive tactics used to apprehend migrants in South Shore and beyond.

“I really sympathize with them,” says Stephanie Stinson, a South Shore resident who lives on a block of brick bungalows and trees still decorated with faded banners from last spring’s Juneteenth holiday. “They have children. They ran away from an oppressive situation and now they are getting their necks stepped on.” She adds, “I’m all for justice and keeping us safe. But I’m not for bullying tactics.”

But not everyone feels this way. “They caused a lot of ruckus – music late at night,” says a man who lives across the street from where the raid took place and gives his name only as Mark. Federal agents, he says, “did what they were supposed to do.”

Changes in South Shore

The raid, which took place in the early morning hours of Sept. 30, stood out not only for its magnitude, with a helicopter and many federal agents, but also for its location. It happened not in one of Chicago’s long-established Latino neighborhoods, as many raids have, but in a Black neighborhood. South Shore has been historically middle class (former first lady Michelle Obama grew up here) but has grappled in recent years with poverty, gangs, shuttered businesses, and boarded-up apartment buildings.

Tensions over the influx of migrants into South Shore arose long before last month’s raid. More than two years ago, the city of Chicago tried to turn a closed South Shore high school into a migrant shelter. Residents pushed back, saying they had not been consulted. Many did not want a large group of migrants housed among them.

“You don’t want it to turn into a hangout spot,” says Larry Petway, a forklift driver who lives across the street from the school.

The shelter never opened. But over the ensuing months, migrants began moving into apartment buildings throughout South Shore, assisted by housing vouchers and other help from the city. They enrolled their children in local schools. They looked for work, bought – and repaired – old cars, and rubbed elbows with Black residents in local stores and at job sites. They stood in line each Tuesday and Saturday with other low-income residents to receive food at the Windsor Park Evangelical Lutheran Church, which stands just a few blocks from the building that was raided.

The numbers alarmed some people. And the level of support for the migrants from Chicago officials angered even many otherwise sympathetic South Shore residents. Chicago spent $639 million on its “New Arrivals Mission” to resettle asylum seekers between 2022 and 2025.

“People were not happy,” says Joyce Gittens, who manages the food pantry at the Windsor Park church and is herself an immigrant from Liberia. She empathizes with the migrants. “The United States is still a nation of immigrants,” she says. But, she adds, “We felt our needs should have been met. We have homeless people living under bridges, in vacant lots.”

Ms. Moyo, who is the founder of Real Men Charities, Inc., and a prominent figure in South Shore, says: “It’s unfortunate that people tend to be pitted against each other for resources. It’s valid that Black people need more resources, and that people who are seeking a better life and are delivered to our doorstep need to be empathized with.” She argues, “We can do both at the same time.”

Dimitri Lewis is a young carpenter in South Shore. He began working on jobs with migrants early on, communicating with hand gestures and cellphone translation apps.

“They never did anything wrong,” he says. “There was never a time when they were trying to bully us.” He feels a sense of commonality with the migrants. “Their fight is deportation,” he says. “Our fight is injustice.”

Some residents see an echo of their own families’ journeys to Chicago in search of a better life. “Because my family migrated from the South to the North after World War II, I understand the whole concept,” says Arlivia Williamson, a volunteer at the Windsor Park church. “Everyone came from someplace else.”

At the same time, the scale of last month’s raid, the militarylike show of force, and the ramping up of aggressive tactics throughout the Chicago region have recalled for some the darker moments of the Black American experience.

“We are descendants of people who had to deal with the KKK and cross burning and lynching,” says State Sen. Robert Peters, whose district includes South Shore. “We’re never going to be OK with masked agents of the government abducting people.”

Indeed, it’s not just the echoes of their own history that have troubled some Black residents in South Shore. The raids have made many uneasy about their future.

“I think a lot of people feel as though it’s going to get worse, that it’s just a prelude to what they’re going to do with African Americans,” says Ms. Williamson. “When they get done with migrants, they’ll come after African Americans. It’s part of the whole ‘Make America White Again.’”

Tension over jobs, community

When migrants first began moving into the big building at 7500 South Shore Drive early this year, many neighbors weren’t happy about it, says James Warren, who manages an apartment complex down the street. “They felt the Venezuelans were going to take jobs and take over the community,” he says.

But it didn’t turn out that way. “It’s not as bad as we thought,” he says. “I even gave some of them work, cleaning up things. They didn’t bother anyone. They just wanted work.”

Still, there was plenty of trouble. A nearby beach became a hot spot on the weekend, with blaring music and sometimes violence, as local gang members confronted the newcomers. “It was chaos,” says Mr. Warren, whose apartment complex stands next to the beach. Meanwhile, drug dealing at the building, a problem long before the migrants arrived, continued, he says, with some migrants taking part. A Venezuelan man was shot and killed in the building in June.

“They didn’t exactly melt into the community,” says Charles Szymanski, a South Shore resident who lives a block from the building. “They were the loudest group in the neighborhood.”

Still, he says the raid troubled him. “You can sit and read about things and look at pictures, and you become accustomed to it, because it’s over there. When you’re seeing it happening firsthand, all of a sudden it hits. These are real people. This is a real situation. The migrants [aggravated] me the past couple summers. But I don’t think anyone wanted this to happen.”

The raid was “more like an insurrection than an arrest,” says Mr. Warren. He was especially offended by the sight of children being pulled from the building. “They were crying,” he says. “They were traumatized. They were screaming for their parents.”

A view from inside the apartment raid

Tenille Lewis lives on the third floor of the building at 7500 South Shore Drive. She remembers how empty and derelict the building felt before the migrants arrived, with mice and garbage and strangers wandering through. The new residents made the building “lively.” She didn’t make friends with any of them, but she greeted them in the halls and in the elevator. She tried to help, answering their questions as best she could. It reassured her that the building had so many residents. There weren’t so many strangers around.

While the situation was far from perfect, most of the migrants were “good people,” she says.

“I have a pretty good sense of people. I didn’t feel any bad vibes with most of them. … Some of the younger guys seemed like the other younger guys in the neighborhood. I didn’t feel any more of a threat from them than from the other guys around here.”

On Sept. 30, the bang of a flash grenade across the hall woke her. Agents busted open her door and demanded to know who was living there. Ms. Lewis uses a wheelchair, and they didn’t force her outside, as they did so many others. But she thought the raid was wrong. It took her neighbors.

“They’re already here,” she says. “They’re human beings.”