A medieval literary puzzle which has confounded scholars for 130 years has finally been solved.

Cambridge University experts now believe the Song of Wade – a long-lost work which dates back to 12th Century England – was a chivalric romance, rather than a monster-filled epic.

They say the discovery finally solves the most famous mystery in Geoffrey Chaucer’s writings, and also provides ‘rare evidence’ of a medieval preacher referencing ‘pop culture’ in a sermon.

The breakthrough, described in the journal The Review of English Studies, involved working out that the manuscript refers to ‘wolves’ rather than ‘elves’ – as experts previously assumed.

Dr James Wade and Dr Seb Falk, both of Girton College, Cambridge, argue that the only surviving fragment of the Song of Wade – first discovered by scholar and ghost story writer M.R. James in Cambridge in 1896 – has been ‘radically misunderstood’ for the last 130 years.

Dr Falk, a scholar of medieval history and history of science, said: ‘Changing elves to wolves makes a massive difference.

‘It shifts this legend away from monsters and giants into the human battles of chivalric rivals.’

Dr Wade, an expert on English literature from the Middle Ages, said: ‘It wasn’t clear why Chaucer mentioned Wade in the context of courtly intrigue.

A medieval literary puzzle which has confounded scholars for 130 years has finally been solved. Cambridge University experts now believe the Song of Wade – a long-lost work by Geoffrey Chaucer – was a chivalric romance, rather than a monster-filled epic

The discovery finally solves the most famous mystery in Geoffrey Chaucer’s writings

‘Our discovery makes much more sense of this.’

Dr Falk added: ‘Here we have a late-12th Century sermon deploying a meme from the hit romantic story of the day.

‘This is very early evidence of a preacher weaving pop culture into a sermon to keep his audience hooked.’

Dr Wade said: ‘Many church leaders worried about the themes of chivalric romances – adultery, bloodshed, and other scandalous topics – so it’s surprising to see a preacher dropping such ‘adult content’ into a sermon.’

In 1896, M.R. James was looking through Latin sermons from Peterhouse’s library in Cambridge when he was surprised to find passages written in English.

He consulted another Cambridge scholar, Israel Gollancz, and together they announced that they were verses from a lost 12th-century romantic poem which they called the Song of Wade.

James promised further comment, but that never came.

More than 120 years passed with no new evidence coming to light.

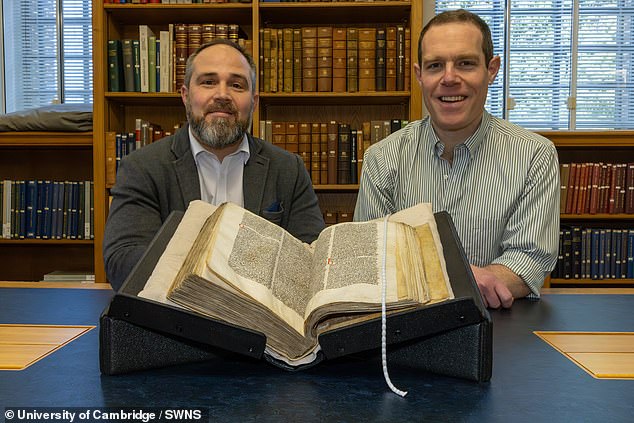

James Wade (left) and Seb Falk (right) with Peterhouse MS 255 open at the sermon

Dr Wade said: ‘Lots of very smart people have torn their hair out over the spelling, punctuation, literal translation, meaning, and context of a few lines of text.’

The present day Cambridge team argue that three words have been misread by scholars, because of misleading errors made by a scribe who transcribed the sermon.

They say the letters ‘y’ and ‘w’ became muddled.

Correcting those and other errors transforms the translated text.

It was previously thought to read: ‘Some are elves and some are adders; some are sprites that dwell by waters: there is no man, but Hildebrand only.’

The new version goes: ‘Thus they can say, with Wade: “Some are wolves and some are adders; some are sea-snakes that dwell by the water. There is no man at all but Hildebrand.”‘

The Cambridge team explained that Hildebrand was Wade’s supposed father.

While some folk-legends and epics refer to Hildebrand as a giant, if the Wade legend was a chivalric romance, as the study argues, Hildebrand was probably understood to be a normal man.

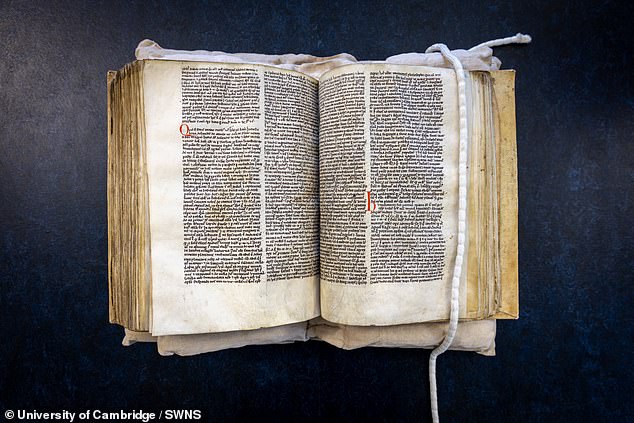

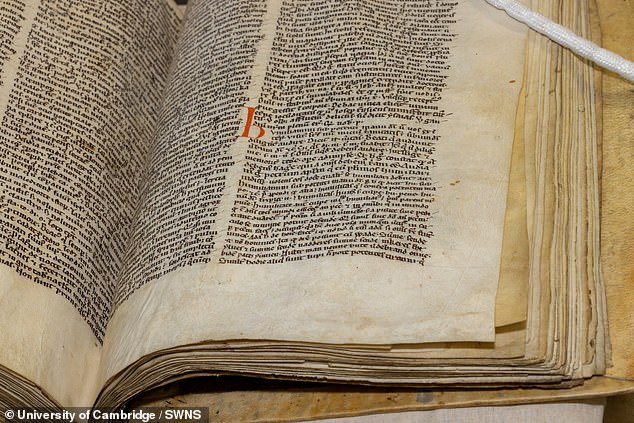

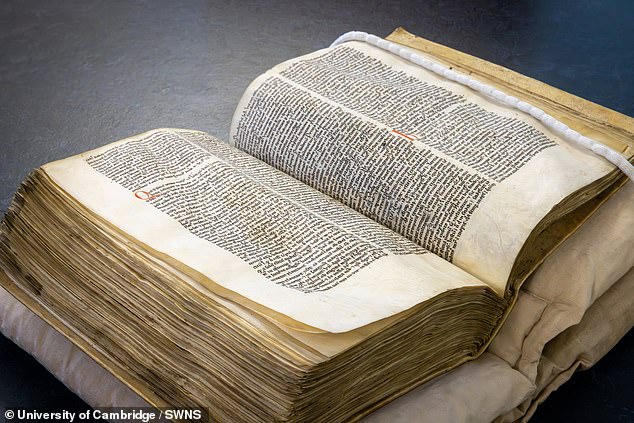

The breakthrough, described in the journal The Review of English Studies, involved working out that the manuscript refers to ‘wolves’ rather than ‘elves’

Wade was a major romance hero throughout the Middle Ages, alongside other famous knights such as Lancelot and Gawain.

Chaucer twice evoked Wade in the late 1300s, but those references have baffled generations of Chaucer scholars.

At a crucial moment in Chaucer’s epic poem Troilus and Criseyde, Pandarus tells the ‘tale of Wade’ to Criseyde after supper.

The new study argues that the Wade legend served Pandarus because he not only needed to keep Criseyde around late, but also to stir her passions.

The Cambridge team say that by showing that Wade was a chivalric romance, Chaucer’s reference makes much more sense.

Chaucer’s main character in The Merchant’s Tale, a 60-year-old knight called January, refers to Wade’s boat when arguing that it is better to marry young women than old.

The Cambridge researchers say the fact that his audience would have understood the reference in the context of chivalric romance, rather than folk tales or epics, is ‘significant’.

Dr Wade said: ‘This reveals a characteristically Chaucerian irony at the heart of his allusion to Wade’s boat.’

The present day Cambridge team argue that three words have been misread by scholars, because of misleading errors made by a scribe who transcribed the sermon

Dr Falk added: ‘The sermon itself is really interesting.

‘It’s a creative experiment at a critical moment when preachers were trying to make their sermons more accessible and captivating.

‘I once went to a wedding where the vicar, hoping to appeal to an audience who he figured didn’t often go to church, quoted the Black Eyed Peas’ song ‘Where is the Love?’ in an obvious attempt to seem cool.

‘Our medieval preacher was trying something similar to grab attention and sound relevant.’

Dr Wade added: ‘This sermon still resonates today.

‘It warns that it’s us, humans, who pose the biggest threat, not monsters.’

The researchers also identified late-medieval writer Alexander Neckam for the first time as the most likely author of the Humiliamini sermon.

The 800-year-old document is part of MS 255, a Peterhouse Cambridge collection of medieval sermons.

The researchers noticed ‘multiple similarities’ in the arguments and writing style of Alexander Neckam, leading them to believe that he probably wrote the sermon.

Dr Falk added: ‘This sermon demonstrates new scholarship, rhetorical sophistication, and inventiveness, and it has strategic aims.

‘It’s the ideal vehicle for the Wade quotation which served an important purpose.’