This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

“And from the castle in the water meadow and the castle on the hill, to the west and Caernarvon, castle of Wales. Wales, where music is mined from the deep ground, where Merlin prophesied and Arthur sleeps, and the sun melts at evening on the sands.”

Christopher Fry, with help from Dylan Thomas and that chap from Stratford, conjured a vivid evocation of our ancient islands, delving deeply into myth to colour his script for the 1953 coronation. In swinging his verbal thurible, Fry gave a whiff of the old religion to the New Elizabethans.

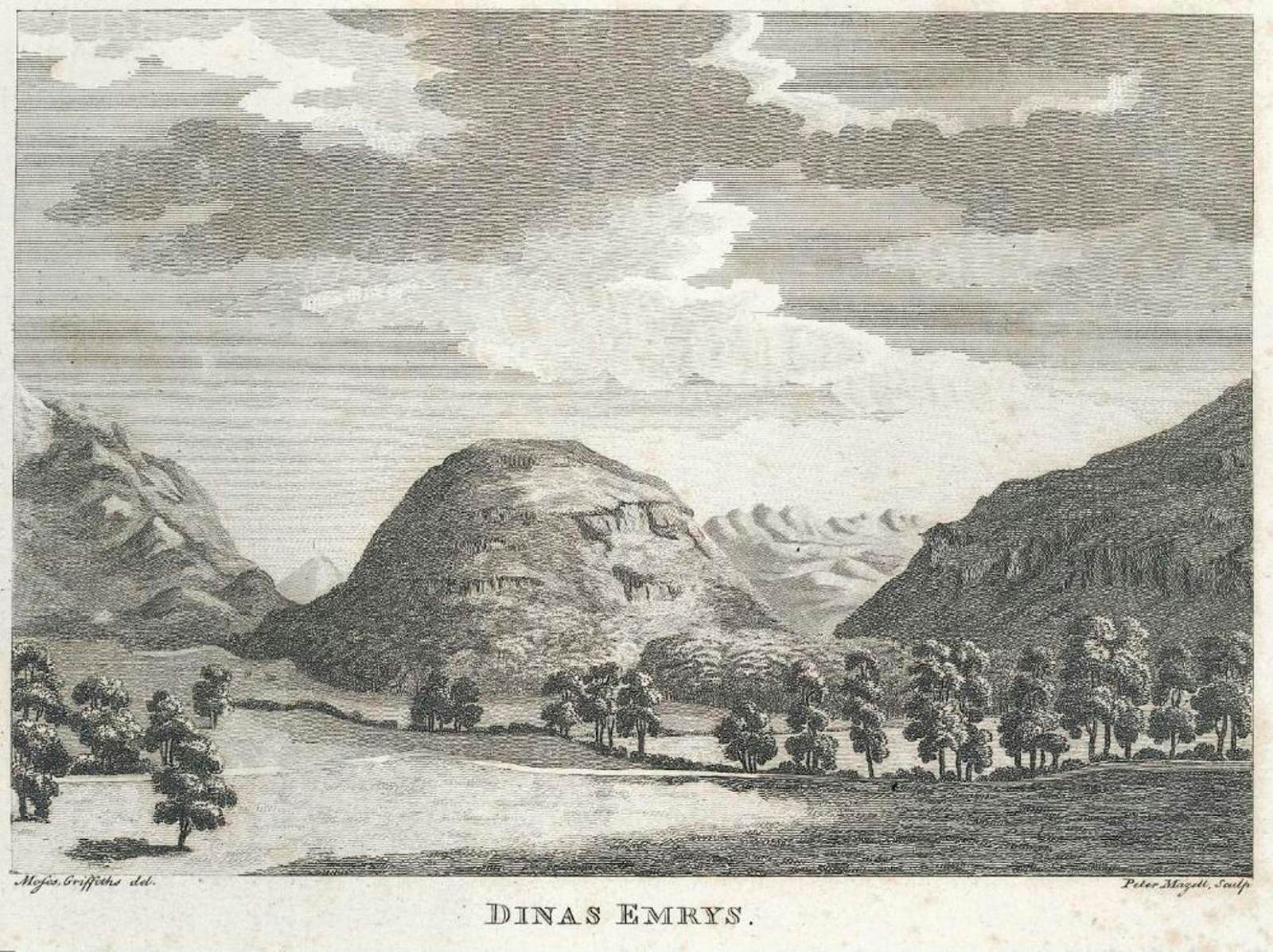

In doctrine even more ancient, in the time of the druids so legend has it, Merlin the magician dwelt at Dinas Emrys high in the mountains of Snowdonia. Here two dragons fought, one white the other red, shaking the soil until the crimson creature emerged victorious to become the symbol of the nation.

Snowdonia is the cradle of Wales, and at its southernmost edge lies the lovely Dysynni Valley, bookended by Cadr Idris and the open sea. Here live two of my good friends, Sir Michael Fabricant, who splits his time between Llanegryn and Lichfield; and screen writer Barry Simner, whose beautiful Welsh longhouse nestles beneath Bird Rock.

In this rugged realm of the buzzard, whose plaintive mew is sometimes the only sound to break the silence, the sky is pierced by the jagged peaks of dead volcanos often shrouded in enigmatic mists. For this terrain is made all the more mighty, not by the burgeoning of spring or the golden blooming of summer, but when the hard weather overhangs the hills. When snow and ice cover the slopes, and the sounds of the modern world are even more muffled, is when this valley is at its most arresting, and sibylline.

Wales in winter is special, and there is something very special about an old Welsh longhouse. Constructed in a single storey and lengthways from the escarpment to protect farmers and their animals from the elements, as well as from rustlers, the people lived at the higher end with the animals in the lower “shippon”. Traditionally whitewashed with the window frames picked out in black, from afar old longhouses appear as natural to the landscape as the sheep with whom they share the hillsides, set amongst gorse bushes and the wind-blasted Welsh oaks.

These days a longhouse is more likely shared with cats and dogs than livestock, but its historic attributions have survived their expulsion — and the introduction of indoor plumbing. Cruck-framed roofs and thick stone walls deter draft and damp, whilst great inglenook fireplaces warm the hearth and the hearts of the inhabitants.

Barry’s home, though not strictly a longhouse, boasts many of these features. Dark slate floors, as smooth as satin, stretch along broad corridors wide enough to herd cows. Enormous timber beams bear the weight of the roof above a bright sitting room looking out across the gardens, a snug den, wherein Barry has assembled his library, and a kitchen in which a Rayburn radiates welcome and by which Geoffrey the cat holds court. In that warm world, talk of Keats and Tennyson mingles with red wine and bara brith as Barry entertains his friends.

Edgar Guest, a son of Birmingham who sought his fortune in America, penned the poem “Where is the road to Arcady?” Had Guest only remembered all those children of his birthplace who made the happy journey west to Tywyn on holiday, he might have concluded the answer lies closer to home. For “Arcady”, read “Aran”.

The road from Welshpool and Llanfair Caereinion, up into the hills of Dinas Mawddwy and through the great pass of Tal y Llyn, by its lake’s placid waters and down to Abergynolwyn and Bryncrug to the shore where, Christopher Fry reminds us, “the sun melts at evening on the sands”.