One of the more iconic moments of Donald Trump’s first presidency came after the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg. As Trump was leaving an event, with Elton John’s “Tiny Dancer” playing in the background, he was told that the famously progressive jurist had passed away.

“You’re telling me this for the first time,” said Trump, spawning his 3,617th meme:

She led an amazing life. What else can you say? She was an amazing woman. Whether you agree or not, she was an amazing woman who led an amazing life. I’m actually saddened to hear that. I am saddened to hear that.

It was oddly powerful, precisely because you would not have expected Donald Trump to seem so moved. Perhaps somewhere inside all of that furious ambition and narcissism, it seemed, he had a heart.

Well, no.

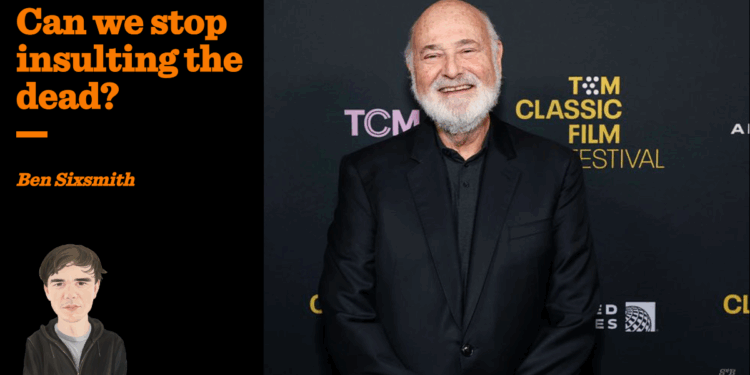

Following the murder of Rob Reiner and his wife, Trump decided to announce that the director had been killed “reportedly due to the anger he caused others through his massive, unyielding, and incurable affliction with a mind-crippling disease known as TRUMP DERANGEMENT SYNDROME”.

This was a lie, clearly, and a lie that made light of a savage murder. Sure, it would have been unfair to have expected Trump to like Reiner, who had indeed played an important role in pushing the dubious “Russiagate” narrative. But if we can’t set political differences to one side when a political opponent is stabbed to death along with their spouse, when can we set them to one side? Trump’s remarks are not so much classless as explicitly anti-class.

Of course, defenders of the President have been quick to point out that a lot of liberals and left-wingers mocked and celebrated the death of Charlie Kirk. Well, none of them had anything close to the status of a president, and Reiner himself condemned Mr Kirk’s murder, but it is true that a lot of left-wing commentators and academics were basking in the death of the Turning Point founder.

A lot of right-wing commentators, including James Woods, the outspoken conservative actor who had been close to Mr Reiner despite their differences, have condemned spiteful comments about the Reiners’ death. This is good, because there is a danger of a cycle of posthumous spite being created as commentators from different political tribes effectively excuse each other’s participation in tit-for-tat contempt.

I don’t think we should feel compelled to behave as if we are sad about people’s deaths. (I’m almost never really sad about people’s deaths, if I’m honest, because I almost never knew them.) I also think that it is fair to be critical about the lives and work of public figures after their deaths. There is no point in being naive about the fact that obituaries are, among other things, platforms for historical contestation.

But one can criticise a life without taking pleasure in a death. Even the transgressive boldness Christopher Hitchens might have displayed when he rhetorically urinated on the grave of Jerry Falwell does not exist in a time of such ubiquitous performative spite.

I prefer to criticise the living rather than the dead

Largely, too — with the exception of genuinely dedicated grudge-holders like President Trump — the celebration of a death comes not from a place of genuine emotion but from a rather sad desire to flaunt one’s tribal loyalty or fearless iconoclasm. (One thinks of the people who would have been suggestive looks between their parents around the time of the miners’ strike who celebrated Margaret Thatcher’s peaceful death as an old woman.)

I have no qualms about criticising people. I’m an opinion columnist for God’s sake. But I prefer to criticise the living rather than the dead. They have at least the theoretical ability to respond — besides which, they might provide me with more copy in the future.

Of course, there are times when someone’s death can be a cause for positive emotion. I don’t think Americans should have had to maintain a respectful silence in the aftermath of the death of Osama bin Laden. But there are not many people who have been responsible for the deliberate murder of thousands of civilians. I’m sure even Tony Blair thought that he was acting in the best interests of almost everyone. (Indeed, his fanatical commitment to this idea is what made him so dangerous …)

Generally, even bad ideas come from sincere beliefs about what is true and virtuous. Generally, even people who make harmful contributions to public life are not doing so out of conscious selfishness or sadism. Generally, even people whose work I despise are loved and loving in private.

Besides, if I have a really good zinger about someone, I want them to read it.