This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

Twice in the last century, Russia stood on the brink of world dominance. Specifically in music, but in other fields as well. Here’s roughly what happened.

In 1914, with German tonality broken and Italian opera exhausted, Russia stood to inherit the earth. It had the world’s most popular composer in Sergei Rachmaninoff and the two busiest radicals in Stravinsky and Prokofiev. The best violinists were pumped out by Leopold Auer’s St Petersburg studio: Mischa, Jascha, Toscha, Sasha. Ballet was rejuvenated by Serge Diaghilev.

Then came war and revolution, and these assets were dispersed. Under Soviet tyranny the composer Dmitri Shostakovich contrived a calculated ambiguity to stay alive, but the pressure to conform inhibited most creative minds. Some, like Galina Ustvolskaya, turned inward and never left home. Others took their cue from Khachaturian and Kabalevsky, composing middle-of-the-road symphonic slush.

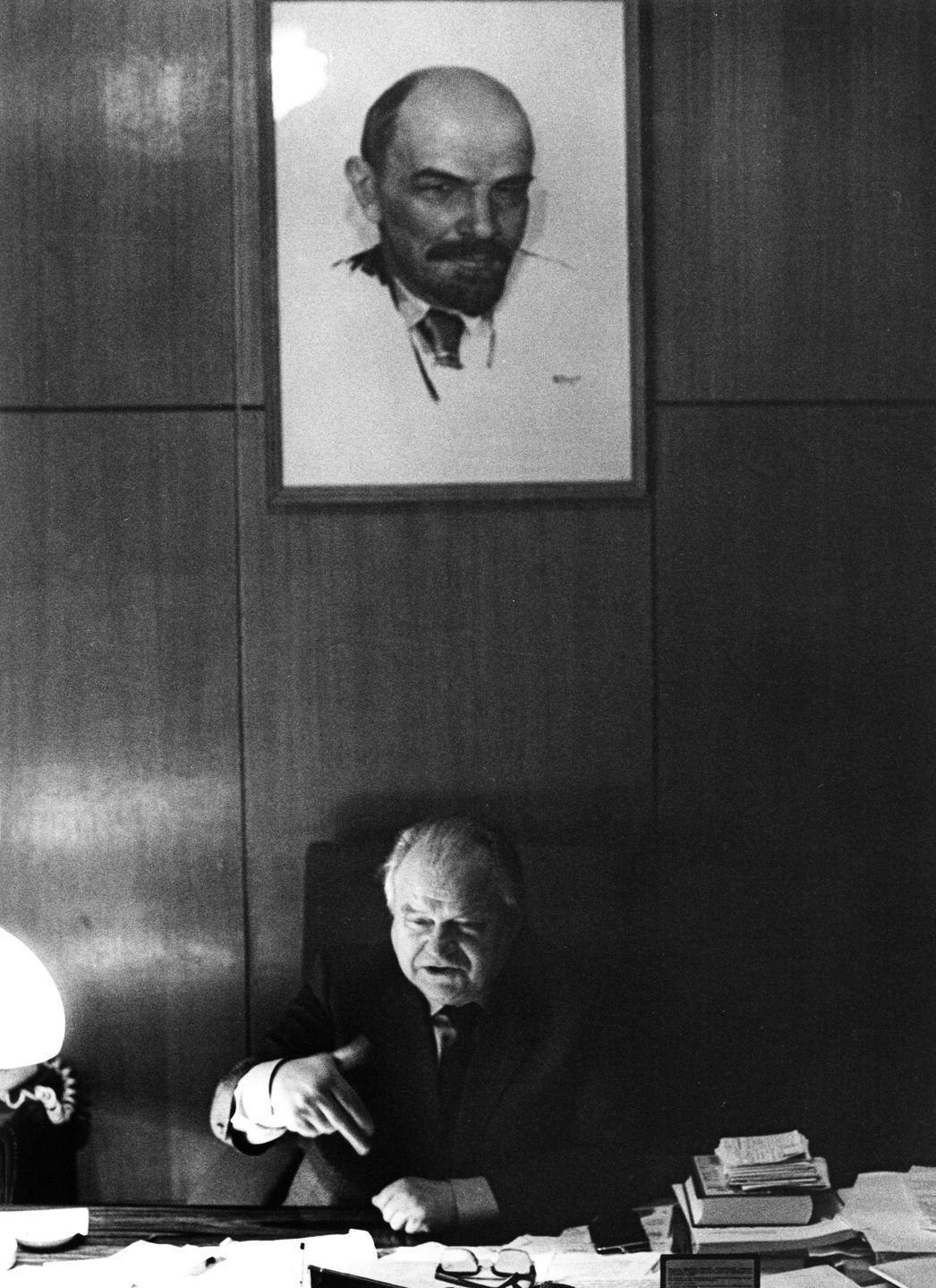

Enforcing the party line was the arch-apparatchik Tikhon Khrennikov who, from January 1948 until several years after the fall of communism, was general secretary of the Union of Soviet Composers.

The Union controlled which works might, or might not, be performed in public. Khrennikov played the system like a mandolin, his favoured instrument.

A perpetual self-promoter in state concerts, I have heard his music highly praised by Valery Gergiev, who serves now as Putin’s supreme commissar for music. (Old Russian habits never die.)

So long as Stalin was alive, Khrennikov ran a dutiful reign of terror. Under the softer hand of Nikita Khrushchev, he kept original voices like Alfred Schnittke and Sofia Gubaidulina alive, giving them movie scores to write. Gubaidulina said she had to take a month in the countryside after submitting a Khrennikov score to state studios.

The wheel turned again under Brezhnev but Khrennikov knew what to do. “When the regime changed,” wrote Schnittke’s friend Alexander Ivashkin, “so did [Khrennikov’s] deputy and the previous one would be blamed … This ensured that Khrennikov remained blameless.”

At the 1979 Congress of the Composers’ Union, the general secretary brutally attacked seven composers who, he said, were making “noisy mud instead of real musical innovation”.

The seven — Gubaidulina, Edison Denisov, Knaifel, Suslin, Artyomov and the married couple Firsova and Smirnov — were denounced as “unrepresentative” of Soviet music and threatened with having their music banned. Schnittke was exempted on grounds of ill health. The stronger ones found ways of getting heard outside Russia.

Denisov, a subversive teacher at the Moscow Conservatoire, kept an open line to Pierre Boulez and Luigi Nono whilst turning out choral works for Russian consumption.

Gubaidulina was a phenomenon — a woman of Tatar-Moslem and Polish-Jewish background who attended Russian Orthodox services, married three times and wrote music of surreal intensity. Reviewing one of her early scores, Shostakovich had told her: “Don’t be afraid to be yourself. My wish for you is that you should continue on your own, incorrect way.”

Having sampled serial, aleatory and electronic music, all strictly prohibited, Gubaidulina formed an officially approved folk instrument group with Suslin and Artyomov, using a wheezy Kazan accordion, the bayan, to add an inimitable patina to her wild orchestral scores.

In the year of the Khrennikov assault she found herself sharing a Moscow taxi with the Latvian violinist Gidon Kremer, who had permission to live abroad.

The outcome was Offertorium, a violin concerto that took a theme of Johann Sebastian Bach as a moral guide to a chaotic universe in which the strangest composed sounds slowly revealed secret connections, like a TV detective in a six-part crime series.

Listening to Offertorium, the ear adjusts to an unknown planetary order. I can describe the work by naming instruments and analysing affinities with Alban Berg’s concerto, but I defy anyone to characterise its essence, beyond hypnotic.

Kremer premiered Offertorium in 1981 to Viennese acclamation. Gubaidulina was not allowed to attend. It was 1985 before she finally sniffed non-Soviet oxygen. By now she was composing mathematical Fibonacci sequences and verses of T.S. Eliot on bongos, John Cage prepared pianos and whatever else came to hand.

When the Soviet Union fell apart, she stood at the peak of a wave of composers whose ingenuity offered renewal to struggling Western concert halls. Once again, the Russians were in the ascendant.

But not for long. At the end of 1991 I wrote a front-page lead in a Sunday newspaper, showing how almost all of Russia’s musical talent had fled. I found Smirnov and Firsova living in an asylum house in Chiswick, West London. Denisov was in Switzerland, heading to Paris. Schnittke was living in Hamburg. Ivashkin was faxing me from New Zealand.

Knaifel died last year in Berlin. His Song of Songs, newly released on ECM Records, has the ethereal regret of an eternal requiem for the musicians of Russia and all they suffered. A solo cello amongst an array of cathedral choirs speaks volumes for the great unspoken. What kind of human-made ideology would ever have suppressed such glories?

Gubaidulina settled in 1992 in a village outside Hamburg, where she kept a samovar on the boil for visitors from the past. Along with Knaifel, she acknowledged a debt in her works to the Kremlin-evicted cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, who provided her in exile with comforts such as a grand piano.

Her Canticle of the Sun, for cello, percussion, strings and choir, is a marvel of modern beauty, if you can train enough voices to surmount its intricacies.

Gubaidulina’s death last month, aged 93, marks an end, not so much of an era as of any hope for the future of Russian music. Might it rise again? In Putin diminution, that seems unlikely.