A new documentary about the Elgin Marbles offers cinematic skill and historical bias

In 2005, the American philosopher Harry Frankfurt published a little black book with the provocative title On Bullshit. The short study — both witty and profound — explored the subtle distinction between the liar, who knows what is true and decides to mislead his audience, and the bullshitter, the person who doesn’t even care about what the truth is, and whose sole purpose is to convince his audience.

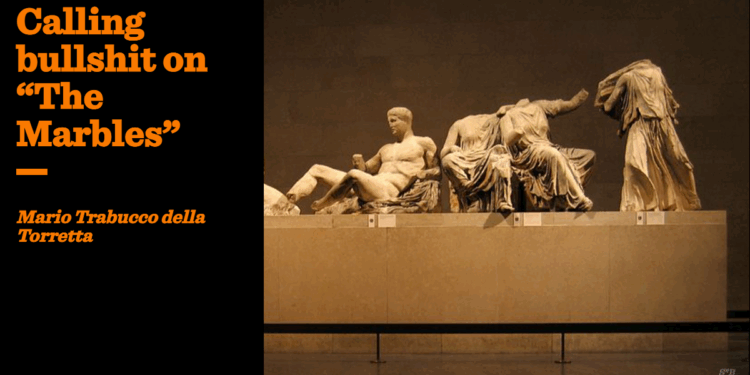

The Marbles, the latest movie directed by David Wilkinson (“Getting Away with Murder(s)”), is a mostly unilateral account of the latest struggles to obtain the return of the Elgin Marbles from the British Museum, where they have been sitting for the last two centuries, to the newly-built Acropolis Museum in Athens. The director, who is also leading the viewer through the various stages of the dispute, presents the material along two main avenues: on one side, the efforts of the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles, with their yearly protests at the British Museum and publicity stunts; on the other, the successful repatriations of various objects from mainly Scottish institutions. The inevitable conclusion is that it is only a matter of time before the British Museum will join the pack in “doing the right thing”.

The word “stolen” must have been uttered at least a hundred times throughout the 113 minutes of the movie

The villain of the story is of course Lord Elgin, the Scottish peer who brought the sculptures to England between 1803 and 1812, and sold them to the British nation in 1816 for £35,000. In the movie, he is presented as nothing more than a pantomime villain, fuelled by greed, ambition, and a Neoclassical taste in matters of home decor. And his family is no better, presented in the movie as some sort of hereditary art crime syndicate. Despite having at least two professional historians in the cast (Prof Paul Cartledge and Dr Dominic Selwood), director Wilkinson chooses to let barrister Mark Stephens present the historical facts, which he does with the same competence as your average butcher explaining Einstein’s theory of relativity. Stephens tells the audience how Elgin “wanted actual pieces to decorate his home”, that he “requisitioned boats and ships” to carry his acquisitions to England, and that the removals were such a scandal that Parliament had to set up a Select Committee to investigate. None of this is true, of course, but it sounds good enough to Wilkinson, so Stephens continues undaunted: “It is pretty clear that Elgin stole the marbles”, “the British Museum is in possession of stolen goods”, and so on. The word “stolen” must have been uttered at least a hundred times throughout the 113 minutes of the movie.

In contrast to the hammering repetition of the word, “stolen”, is the demeanour of the co-villain of this story: the British Museum, whose silence is “obdurate” and “rude”, according to Dame Janet Suzman, BCRPM chair and one of the stars of the movie. Wilkinson informs the viewer that he repeatedly tried to engage with the Museum, but without result. All he got is a scripted statement, which mechanically references how the Marbles were “legally acquired” and kept for all the world to see. This is probably the only point where I find myself closer to Wilkinson: the British Museum is the worst possible defender of its right to own the items in its collection. They should engage with the debate, illustrate the details of the acquisition, and popularise the ample scientific research existing on the subject. Retain, yes; but — by Jove — explain!

Yet an obstinate silence doesn’t make a villain. And that’s when the viewer is presented with the loan of the Ilissos statue to none other than Putin’s Russia, the scandal of the theft from the storerooms, and the possession of other contested objects, such as one of the moai from Easter Island. However, unlike Elgin, the museum is not a cardboard villain. It has some redeeming features: it can count on assets like the new chair of the Trustees, George Osborne, who initiated a dialogue with the Greek government after years of institutional silence. And it can count on loving and caring employees (such as the director’s own daughter, Pip), who just do as they are told and make the best of a difficult situation. All going well, the British Museum will eventually redeem itself — returning the Marbles and narrowly escaping the fate of Northampton Museum, reduced to “a pariah in the museum community” for not worshipping at the altar of restitution.

To look for the solution, we need to look away from London: “Frown not on England; England owns him not: Athena, no! thy plunderer was a Scot” wrote Byron of Lord Elgin. It falls, therefore, on Scotland to be the hero of the story and show the path that leads to museological salvation. After all, if we are to believe Brian Cox, “had [the Marbles] been in Scotland, they would be back already”. A great argument against Scottish independence, if you ask me. It is so that we are accompanied on a transformative journey, witnessing the gradual morphing of the “Athens of the North” into “the world leader on restitution”. From Lakota ghost shirts to Benin Bronzes, from Glasgow to Aberdeen, Wilkinson introduces us to curators proudly dismantling their collections on moral grounds (whose morals?), and grateful communities that only had to ask nicely to obtain what they wanted.

The nettle of the story comes back to what Stephens said early on: “if you steal something, you don’t get title”. Don’t tell that to Elgin, who, even having “stolen” the Marbles, didn’t get the British peerage he so wanted. Jokes aside, the core of the issue, and the most enormous hole in Wilkinson’s carefully constructed narrative, is indeed that little “if”. Sure, let’s talk about the restitution of stolen property. But where is the evidence that there was ever a theft in the first place? The so-called firman is allowed to make a brief appearance, immediately to be dismissed by Stephens as irrelevant because “there is no good reason to have it in Italian”. Little does he know that Italian was a lingua franca for Westerners in the Ottoman Empire and Italian were the artists who benefitted by the liberties granted by the document. At any rate, all this discussing of evidence is boring and unimportant — “it might have felt right in the 19th century, but it is wrong for the 21st century” says Victoria Hislop. End of. In the end, it appears that local museums and minor galleries are willing to return items on a lower standard of proof anyway, in exchange for the prized label of restitution champion. Surely this cannot be the case for national museums and assets of prime cultural significance?

This movie reminded me of the book on the Parthenon Sculptures by Christopher Hitchens: marvellously narrated, but factually incorrect

Early in the movie, Patricia Allan, former curator of World Cultures at Glasgow Museums, called for “a bigger national debate” on this topic, and I agree wholeheartedly. However, having a debate cannot be a euphemism for “reaching predetermined conclusions”. For such a debate to be meaningful and productive, it is necessary to begin with a solid interpretation of the evidence. And this is the movie’s biggest disappointment. You may have noticed, by now, that I have so far refused to describe this movie as a documentary, which is the way Wilkinson introduces his creation in the opening lines. The reason is that for a documentary to deserve that classification, it is necessary to register an ambition to be objective and balanced, to enlighten rather than obfuscate, to go deeper instead of relying on a few gut punches to make your point. This is a brilliant piece of activist cinematography, of propaganda, or at best a monumental ad for the BCRPM.

Was it all that bad, then? During the animated live Q&A with the director, I mentioned that this movie reminded me of the book on the Parthenon Sculptures by Christopher Hitchens: marvellously narrated, but factually incorrect. I stand by this judgement. Don McVey’s stunning cinematography captures the majestic character of the Duveen Gallery and the beauty of its content in such a way that it is difficult to think they could be presented in any other way (they can, but that’s another story), and Christopher Barnett’s poignant soundtrack adds structure and a dramatic solemnity to the subject. Credit is also due to Jonathan Guy Lewis for his impression of Boris Johnson.

Overall, the movie could have lasted a good twenty minutes less, cutting out irrelevant material such as gratuitous condemnations of a few Conservative prime ministers. Perhaps this time could have been filled with a deeper understanding of what prompted Elgin to bring over the Marbles in the first place, or an exploration of the abundant historical evidence in support of Elgin’s side of the story. But this omission won’t hurt the movie’s chances with its intended public. As a member of the audience put it during the Q&A, “it doesn’t matter what the documents say, they should be back!”

For all the rest of us, who actually prefer to explore thorny issues with objectivity and solid evidence, I must call bullshit.