In public, he presented himself as a calm and confident leader, dressed in neat suits and speaking with a promise of peace and rebuilding Liberia.

But behind that persona stood a man linked to some of the worst violence in modern African history.

Under Charles Taylor’s influence, armed groups in Liberia and Sierra Leone carried out killings, mutilations, forced recruitment of children and widespread sexual violence.

His reign of terror has been documented as one of the most brutal in the history of the world.

Rights groups say that during his rise to power and barbarous presidency, 250,000 Liberians were murdered, while hundreds of thousands were raped, maimed, and mutilated across the two Liberian civil wars.

Liberia was already deeply unstable long before Taylor rose to power. In 1980, Master Sergeant Samuel Doe seized control of the country in a violent coup, and his forces soon became notorious for torture, ethnic killings and executions.

His rule deepened mistrust between communities and drove Liberia into a political and social collapse that created the perfect opening for Taylor’s rebellion. Doe’s own fighters massively contributed to the atrocities.

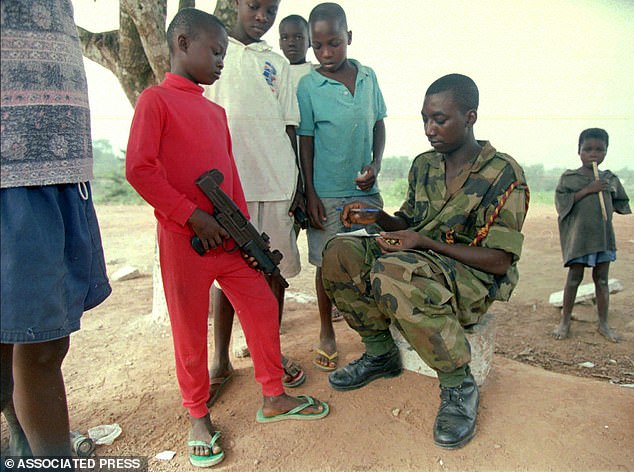

Children were among the very first victims – Human Rights Watch documented the recruitment of boys as young as ten in Liberia.

Many were taken from villages or caught at roadblocks. One boy told Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) that he was dragged from hiding and forced to hold a rifle while fighters ordered him to shoot a captive.

When he hesitated, he said the fighters threatened to kill him. He said ultimately, he fired the weapon because he believed he had no other choice.

Other boys interviewed by investigators described seeing adults executed and being told they would be killed as well if they refused to join.

One of the most cruel accounts involves child soldiers who were forced to participate in the murder of their own parents as a form of initiation. Refusal often ended in their own deaths.

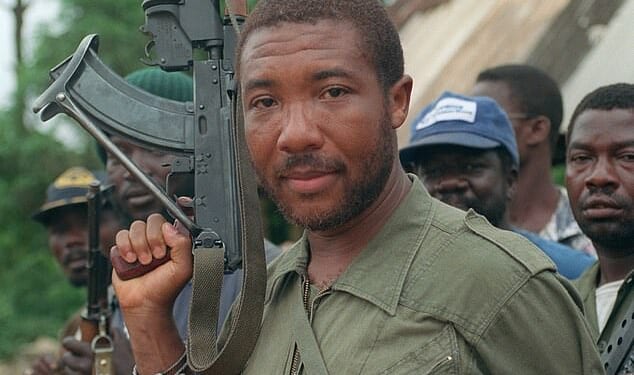

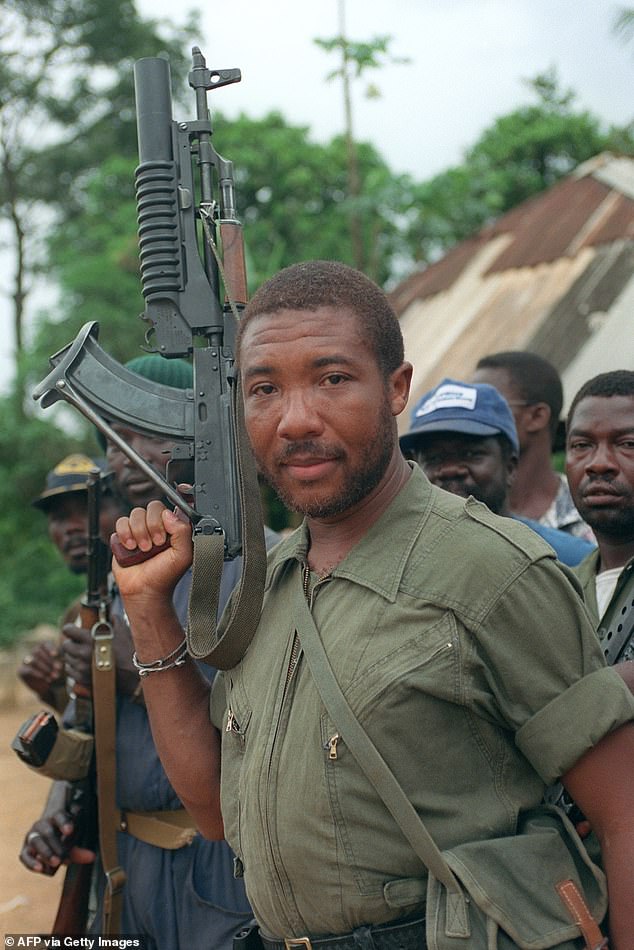

Charles Taylor in his days as a rebel leader in May 1990. Liberia still carries deep scars from the atrocities that were committed by fighters loyal to him and Doe

Older rebel fighters wrestle a gun out of the grips of a young fighter who was caught looting with it in Monrovia in 2003

A 12-year-old fighter seen with his gun in January 1997. He was recruited to fight in the war when he was just eight

Once recruited, many children were drugged. Horrific accounts have described the use of a mixture known as brown brown, a blend of cocaine and gunpowder that fighters rubbed into cuts on children’s skin.

Survivors said the drug made them dizzy and confused, with some saying they fired their guns without control because their hands shook.

Commanders sometimes tied ropes around the waists of the smallest boys so they could pull them forward during attacks.

Many children were also forced to watch as soldiers beheaded, burned alive, and tortured people they knew in their communities. They were threatened that they would be killed if they screamed while witnessing the brutalities.

This was seen as a tactic to disassociate them from their communities and dehumanise them so that they become cold-blooded killers.

The Small Boys Unit in Liberia saw boys as young as eight serve as fighters, porters and bodyguards.

Many died in ambushes or during reckless attacks. In Sierra Leone, UNICEF reported similar groups known as Small Boys Units and Small Girls Units. Boys were used as scouts and messengers and faced severe punishment if caught.

In 2012, a former child soldier, Prince ‘Small Soldier’ Kamara, described some of the battles he was forced to engage in to the Independent. He said: ‘The scent of gunpowder, eyes stinging from smoke, your friend crying… it was terrible.

‘I missed my mother at that moment. But then we captured some Nigerian peacekeepers, took them to our HQ. Then I felt so proud. People called me a big man.’

Some children also joined the fighters to avenge the deaths of their loved ones, while for others, it was simply a case of survival as they had been left orphaned.

A child soldier fighting for Charles Taylor’s government. While some children joined to avenge the deaths of their parent’s, others simply wanted to survive

Samuel Doe, the country’s president at the time Taylor rose to prominence also took part in the atrocities. His fighters committed many massacres, burning whole communities down

The suffering was not only limited to boys – Amnesty International and the Special Court for Sierra Leone recorded widespread abductions and sexual slavery of young girls.

Fighters took girls and kept them as what survivors called bush wives. They were raped repeatedly, beaten for resisting and forced to cook and clean.

One woman, Diana Korgbaye, describing her ordeal, which began when she was a minor, said: ‘In war-time, there’s no real love. I was raped before I knew about those things. He forced me to be his wife. He had about 30.’

Another girl testified that she was taken in her early teens and raped over a long period. She said: ‘They abducted five girls coming from church. They took us to the front line.

‘We had to cook and carry ammunition in the bush. They treated us bad; if I didn’t go [have sex] with them, they would kill me… I want to go to school. I want to go back to Nimba to my people.’

A teenage girl told investigators she fainted after several fighters raped her. Médecins Sans Frontières staff treated women with life-threatening injuries caused by repeated assault.

There were several cases of girls forced to give birth in the bushes with no medical assistance whatsoever. Others who managed to seek help at clinics arrived unable to walk because of severe injuries. Many died attempting to give birth.

In 2004, it was determined that between 60 and 70 per cent of the country’s civilian population had either been raped or sexually abused.

Women were often rounded up and gang raped in front of their helpless children and husbands.

Alongside the atrocities committed against minors, entire communities were destroyed.

One of the worst massacres took place at St Peter’s Lutheran Church in Monrovia in July 1990, where more than 600 civilians were killed. Most were women, children and elderly people who had sought shelter inside the church.

The bloody aftermath of the church massacre. Items of clothing are seen scattered across the floor as pools of blood remains

In 2009, villagers exhumed the remains of several people thrown in mass graves in Kpolokpai for reburial. The Kpolokpai massacre killed an estimated 250,000 people between 1989 and 2003

The horrific killing was carried out by soldiers loyal to president Doe, who believed that civilians hiding inside were sympathetic to the rebels fighting against his regime.

Fighters surrounded the building and fired through the windows and doors. Survivors told investigators that people fell on top of one another as they tried to hide.

One woman described bullets coming from every side and said she believed no one inside was meant to survive. When fighters entered the church, they stabbed and shot anyone who was still alive.

UN investigators later described the interior as a scene of overwhelming devastation.

Other villages faced a similar fate. UN teams sent to communities in Lofa County found huts burned to the ground, bones scattered on the ground and homes reduced to ash.

Médecins Sans Frontières reported finding burned bodies inside houses in places like Buchanan and Totota.

Villagers who returned said they found personal belongings among the rubble but no survivors. Liberia’s TRC collected testimony from people who said relatives were taken from their homes and never seen again.

Torture was widespread. Survivors told investigators that fighters used nails, ropes and rifle butts to punish captives. Some said they were nailed to trees through their hands or feet.

Others described being beaten until they lost consciousness. Witnesses told the TRC that men were buried up to their necks and left under the sun with insects crawling over their faces. A BBC correspondent detained by fighters said he heard screams through the night from nearby buildings.

Across the border in Sierra Leone, the brutality escalated – the Revolutionary United Front (RUF), supported by Taylor, carried out mutilations that shocked the world. The RUF fought an 11-year war in an attempt to overthrow president Joseph Momoh.

Gruesome images showed how innocent citizens were buried in mass graves after executions at the hands of barbaric fighters

Rights groups documented the practice known as short sleeve or long sleeve, in which rebels forced civilians to choose between having their hands cut off at the wrist or their arms severed above the elbow.

One widely documented survivor, Mariatu Kamara, was 12 when rebels cut off her hands.

She later told UNICEF that she had not understood the choice rebels demanded, so they made it for her. Another survivor described being cut in front of neighbours before being left to bleed.

Some of the worst violence involved large-scale executions. In Liberia, the Maher Bridge massacre was one of the deadliest incidents of the late years.

Amnesty International reported that in 2002, government forces rounded up around 175 civilians in Bomi County.

Witnesses said the victims were taken to a bridge, shot and thrown into the Maher River. Liberia’s Independent National Commission on Human Rights later confirmed the site as one of the country’s major massacre locations.

Sierra Leone suffered similar horrors – during the 1999 assault on Freetown, known to fighters as Operation No Living Thing, Human Rights Watch reported that more than 7,000 people were killed, at least half of them civilians.

Rebels burned homes with families trapped inside. Survivors described people being shot at close range while trying to flee.

Colonel Michael Tilly, right, seen with his fighters. He was the leader of the Death Squad, a faction of president Doe’s armed forces and oversaw the killing of the 600 people at the St Peter’s Lutheran Church

A government soldier opens fire against rival factions at the Via Town bridge in April 2004

UN investigators reported that civilians were used as human shields as rebels fought their way through the city.

Even water sources became sites of horror. The World Health Organisation reported in 2003 that the Liberian Red Cross found bodies dumped in wells in Buchanan.

Witnesses said the remains were thrown in during fighting, contaminating water that survivors needed to drink.

Later prosecutions in Europe concerning wartime crimes included witness descriptions of civilians thrown into wells or rivers across rural areas.

The origins of Liberia’s collapse ran deep – for more than a century, political power was held by Americo Liberians, a small elite who dominated government and commerce. Many indigenous communities felt excluded.

Tensions grew for decades, and in 1980, Samuel Doe led a coup that overthrew the old order. Doe came from the Krahn ethnic group and soon filled senior positions with Krahn allies.

His rule became known for corruption, political arrests and executions. The economy weakened. Relations between Doe’s supporters and the Gio and Mano communities in the north worsened. By the late 1980s, the country was unstable and close to collapse.

Charles Taylor entered this environment in 1989 – he had studied in the United States and had escaped from a Massachusetts jail after being accused of embezzling government funds.

He later travelled to Libya, where he received military training. In December 1989, he crossed into Liberia from Côte d’Ivoire with a small armed group.

They captured towns quickly. Other factions formed soon after, including groups that opposed both Taylor and Doe, sparking huge fighting across the country.

Bones and skulls seen in Kpolokpai, Liberia in September 2009. A church service was organised for the dead after their remains were dug up

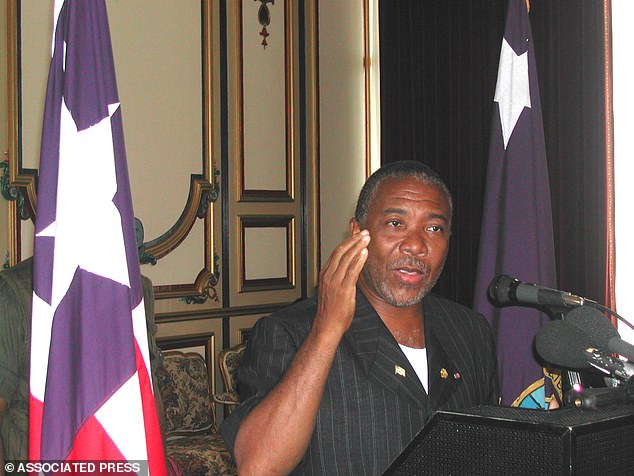

Charles Taylor addressing journalists in 2003. He entered Liberia’s political space with the promise of reform and change. What ensued, however, was some of the bloodiest atrocities ever recorded

Markets were burned, schools destroyed, and villages forced to flee. By 1996, Monrovia had been destroyed several times during battles between rival militias.

The 1997 elections offered a fragile chance to end the war, with a win for Taylor.

Some voters told journalists they supported him because they feared that refusing to do so would bring more fighting.

Once in power, he consolidated control. UN reports later described how he supported the RUF in Sierra Leone with weapons, communications equipment and political backing.

Taylor denied these allegations, but evidence of his support appeared in several international investigations.

In 2003, the Special Court for Sierra Leone indicted him. Under pressure from regional leaders, he resigned and went to Nigeria.

Olusegun Obasanjo, president of Nigeria at the time, granted him asylum, drawing international criticism.

In 2006, he attempted to flee but was arrested near the Cameroon border. He was flown to The Hague to stand trial.

The trial lasted almost six years and became one of the most significant war crimes cases since the Second World War. The Special Court for Sierra Leone moved the proceedings to The Hague for security reasons.

Judges heard from amputees, rape survivors, child soldiers, former fighters, UN experts and people who had once been close to Taylor.

Taylor at the Special Court for Sierra Lone in The Hague, Netherlands in July 2009, where he answered for chargers of leading rebels murdered, raped, and mutilated villagers

Many walked into court without arms or legs, while others carried scars from burns or beatings.

Prosecutors argued that Taylor supported the RUF, knowing that the group was committing murder, rape, mutilation, enslavement and the recruitment of children.

They presented radio logs and documents showing contact between Taylor’s office and RUF commanders during major attacks.

UN panels and groups like Global Witness provided evidence connecting diamonds mined under violent conditions to networks linked to Taylor’s presidency.

Some insider witnesses gave mixed accounts – a former fighter testified that he helped transport weapons into Sierra Leone and said that rebels carried diamonds back into Liberia. Judges treated some of his more extreme claims with caution.

Taylor’s former vice president testified that he never saw Taylor take part in ritual acts but said he could not rule out that such acts might have taken place beyond his view.

Former RUF leader Issa Sesay testified for the defence. He said he did not fight for Taylor and did not personally give him diamonds.

Victims also told their stories. An amputee said rebels who cut off his arms told him they wanted him to carry a message of fear.

A woman described being raped by fighters who said they were waiting for support from Liberia. Former child soldiers said they saw ammunition arrive before major attacks.

Bullet casing filled the streets of Monrovia as fighters battled it out, killing many cilvilians in the process

Their accounts helped judges build a picture of how the RUF operated and how outside support allowed them to continue.

In April 2012, the court found Taylor guilty on all 11 counts, with judges ruling that he aided and abetted war crimes and crimes against humanity, including murder, rape, sexual slavery, mutilation, enslavement, acts of terrorism and the use of child soldiers.

In May 2012, he was sentenced to 50 years in prison, and his appeal was eventually rejected. He was moved to HM Prison Frankland, a high-security prison in the United Kingdom, where he remains.

As for Samuel Doe, he faced his own gruesome reckoning much earlier. In September 1990, he travelled to the headquarters of the rebel group INPFL, believing it would be for peace talks.

Instead, he was ambushed by fighters loyal to warlord Prince Johnson, who was affiliated with Taylor.

Johnson’s men seized him, stripped him, beat him and taunted him while a video camera recorded the entire ordeal.

The footage, which later circulated internationally, showed Doe bleeding heavily as the rebels cut off his ear and continued to interrogate him.

He was tortured for 12 hours, with some of his toes and fingers amputated. By the time the fighters finished with him, Doe was barely conscious. He eventually died from his injuries.

His mutilated body was displayed naked publicly, signalling the complete collapse of his regime and the total fracture of Liberia’s political order.

Doe was captured and tortured for hours in September 1990. His naked, mutilated body was displayed in the streets

Liberia still carries deep wounds – former child soldiers struggle with trauma, addiction and unemployment. Many never returned to school. Several infrastructures, like schools and hospitals, were destroyed.

Women who survived rape face stigma and limited access to support. Communities destroyed during the conflict remain impoverished.

Sierra Leone still has thousands of amputees who rely on aid. Families remain separated. Mass graves across both countries hold the remains of people who never made it home.

The legacy of Charles Taylor is seen in the burned villages, the missing limbs, the abandoned fields and the survivors who still whisper the names of those they lost.

He sits in a British prison, far from the countries where his decisions caused so much pain.

To many in Liberia and Sierra Leone, he is not remembered as a president but as the man whose wars scarred a generation and left behind suffering that will not fade for decades.