This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

In 2001, Tony Blair’s new Foreign Secretary, Jack Straw, wanted to make his mark. However, his freedom of action was limited because budgets were tight. What to do? Where might savings be made or — better than cuts — how might the assets of Britain’s past be made to pay for the commitments of the present? And so the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (as it then was) set about doing what we are advised absolutely never, under all but the most extreme circumstances, to do — which is sell a little of the family silver to fund current cash flows. In this instance, that meant the lush, beautiful, tree-filled grounds of the handsome and impressive British Embassy in Bangkok.

The bean-counters got to work and were advised that they could realise over £50m for the plot. £50m was a lot of money, except in the context of British government spending, where the sum represented a few hours of debt interest. But what Straw and his senior civil servants failed to undertake was any material cost-benefit analysis of the sale: what it meant for the UK’s reputation as a hitherto quietly influential friend and trading partner.

Business always seeks reliability, commitment and a long-term view from their international trading partners and suppliers. The (mathematically unquantifiable) cost of foregone goodwill must surely have contributed to the fact that UK exports to Thailand were £2.7bn in 2018 and were, by 2024, still £2.7bn — during which time Thai exports to the UK increased markedly. Whatever the long-gone cash benefits from the sale, they left no positive bounty for Britain’s reputation in Thailand.

In 1855 the British and the Siamese signed the Bowring Treaty, which opened up foreign trade with Siam (the kingdom was renamed Thailand in 1939). The following year the British opened a legation on the Chao Phrya river, on land generously gifted to them by Siam’s monarch, King Mongkut. The treaty worked as intended and many British companies came to Thailand: Hong Kong and Shanghai Bank, Chartered Bank, Bombay Burmah, The Borneo Company and many others. A railway to the southwest was built by an Englishman; a golf course en route by a Scotsman; and in 1862 the Anglo-Indian, Anna Leonowens, was hired as a governess at the Court of King Mongkut.

As the decades passed and as the city of Bangkok spread east, away from the river, a new legation site at the junction of Ploenchit and Wireless Roads was purchased from the Nai Lert family in the early 1920s, the purchase being partly financed from the proceeds of the sale of the river site earlier gifted to them by the king. The new legation (thereafter embassy) was completed in 1926 with the departing diplomat Sir Robert Greg, who narrowly missed occupying it, consoling himself with “what is a few weeks’ delay, when you have built almost for eternity?”

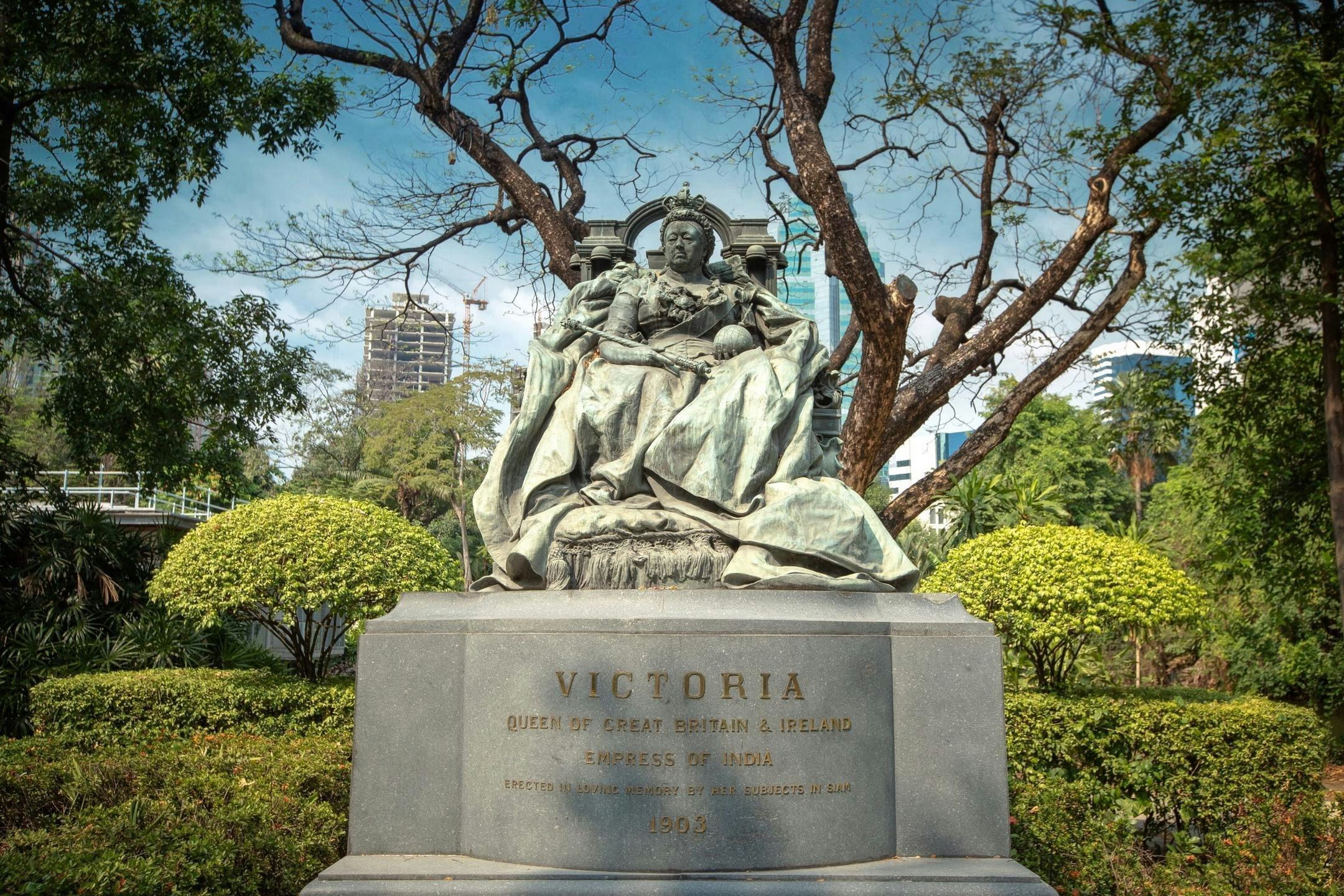

The handsome buildings and beautiful grounds were in harmony with each other. Flame, Rain and Acacia trees abounded; a large klong (lake) added some calm; and the gardens provided a home for butterflies, birds, the War Memorial and for a Sir Alfred Gilbert three-tonne statue of Queen Victoria — paid for by voluntary donations from British expatriates and Chinese-British subjects then working in Thailand.

The compound became even more of an oasis as the city expanded around it — a green lung for which Bangkokians were grateful. Queen Victoria stood comfortably, grandly and yet benignly behind the wrought iron gates on the corner of the compound, visible to all. She was seen as a symbol of fecundity by many Thais and as a place of pilgrimage for those seeking divine help to conceive. Many Thais, as they walked past her made the wai, a respectful Thai greeting.

And then came Jack Straw. The gardens were sold to a delighted and probably astonished Central Group, a Thai conglomerate, in 2006 and not long afterwards in came the chainsaws and the bulldozers to wreak havoc. Many ancient, beautiful trees fell to the saws and some smaller, period buildings came down too. The birds and the butterflies fled.

But the main embassy buildings still stood tall and impressive, visible symbols of British commitment to Thailand and to the many British residents and visitors. They had reason to hope that this duty would remain because, in a letter to the Clerk of the Foreign Affairs Committee of the House of Commons dated 15 May 2006, it was stated that part of the proceeds of the land sale would go to the refurbishment, modernisation and upkeep of the embassy buildings. The Embassy was safe.

Except that it wasn’t. The embassy limped on in its amputated state for another 10 years until another wrecking ball swung into view, this time in the shape of Boris Johnson, Foreign Secretary for a short period during Theresa May’s government.

Johnson decided to sell the remaining grounds and buildings in 2017, although the “blob” had most probably made this decision before his arrival on the scene — hence the lack of institutional outcry — and there might have been little he could do, even if he had wanted to. Which he did not.

Central Group, to whom the embassy was sold for £240m in January 2018, could not believe its luck: to gain yet another piece of prime real estate in such a location at almost any price was beyond reasonable expectations. The following month whilst on a visit to Bangkok, Boris Johnson told the writer Simon Landy at an embassy reception, “We’ll get a shiny new property. Recalibrating the relationship for the twenty-first century! Onwards and upwards!”

The relationship was indeed recalibrated but not in the direction Johnson had boasted. When the demolition teams started work, the Thais looked on utterly aghast as one of Bangkok’s few remaining period buildings was smashed to pieces and turned to dust. The treasured small green lung had gone, later to become yet another shopping centre called Embassy Mall. The site of the beautiful buildings became, and remains, an empty building plot.

Shortly after the oasis of calm and diplomacy was reduced to rubble, two businessmen, one American and the other European, surveyed the scene of devastation in quiet amazement until one asked of the other, “What don’t these Brits understand about brand?”

The most visible sign of outrage at the destruction was the decision by the Association of Siamese Architects to recall the Award for Outstanding Conservation of Architectural Arts from the British Embassy, awarded in 1984 for the (then) efforts to conserve the embassy building. The less visible but rather more material sign was the largely unspoken and faintly embarrassed acceptance that the British state had accelerated the management of its own decline by downsizing in Thailand, waving goodbye to more than one hundred years of accumulated soft power.

That soft power had been effectual. Indeed, so Anglophile were the Thais that in living memory four prime ministers — Seni Pramoj, Kukrit Pramoj, Abhisit Vejjajiva and Anand Panyarachun — had been schooled in the UK. Thousands of Thais had been to British universities; and British independent schools, warmly welcomed by the Thai state, have opened up in Thailand in recent decades. It is unlikely that the extreme discourtesy the British showed towards their generous and gentle Thai hosts will easily be forgotten or forgiven although the Thais, with their beautiful manners, would never of course suggest as much.

It was claimed that the proceeds of the sale would help modernise other British embassies and pay for the move to new premises in Bangkok. In 2018 with the deal complete, Boris Johnson issued a statement promising, “Our workforce in Bangkok will be moving into a state-of-the-art premises by 2019 and this can only enhance our trade links and bilateral relations in Thailand and throughout the region.”

With this waffle he parroted Simon McDonald, the Permanent Under-Secretary at the Foreign Office, who offered up the same platitudes: “This deal will ensure that we have a modern, state of the art premises in Bangkok, confirming our long-term commitment to our relationship with Thailand.”

What of this “state of the art premises”? The embassy is now housed on floor 12a of the AIA Sathorn Tower, a forgettable, anonymous office block hosting lawyers, accountants and a steel company, well away from the diplomatic quarter, on a hugely busy road and not far from the elevated railway.

Not next to an elevated railway station of course, just the railway. Few people even know where it is. Those who have visited it would find the idea that it expressed a higher prioritising of interest in Thailand laughable. “Global Britain” was meant to be tilting away from Europe towards high growth regions like South East Asia with their booming economies and young and dynamic workforces. Perhaps Boris didn’t pay enough attention to his own Brexit script.

As for the magnificent statue of Queen Victoria? Well, it seems to have been mislaid. Nobody can say with any certainty that they know where it is. Some say it is in a warehouse, waiting to be installed in a new mall in a grotesque, Disneyesque pastiche of history and of what once was. Others say it is lying at the bottom of a klong. Naturally, no politicians or civil servants have been held to account for the misplacement.

Not all was lost however. Embarrassed by what had happened, members of the British Club — a club for British business people and expats in Bangkok — came to the rescue of the war memorial which records the names of the Britons living in Thailand who answered the call in 1914 and again in 1939 and were killed in the two world wars. The memorial now stands on the corner of the garden in front of the clubhouse. It is cared for, respected and appears to be, to this writer at least, comfortably at home.

Contrast the attention to our history, reputation and future paid by the private members of the British Club with the empty words on the British government’s History of Government blog of 15 April 2019 which described the sale as “another milestone in British diplomatic endeavour, as we invest in the future whilst honouring our heritage through reminiscence”.