A 120-year-old letter in a bottle offering a snapshot into the hardships of life under the rule of Russia‘s last Tsar has been found in Poland.

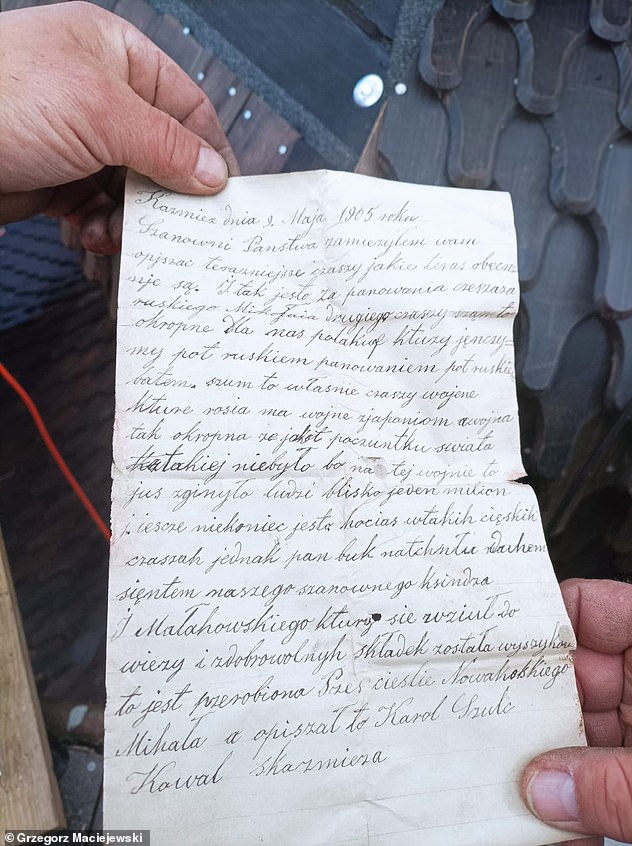

Penned in May 1905 by a local blacksmith named Karol Szulc, the ‘time capsule’ letter was discovered during conservation work at the 16th century Benardine monastery in the village of Kazimierz Biskupi.

Builders stumbled across the letter detailing the hardships under Tsar Nicholas II while dismantling a cross on the monastery’s gate tower overlooking the village.

Beginning ‘Dear Sirs’ the short letter written on a single sheet piece of paper in flowing cursive text says: ‘I intended to describe to you the present times that are now.

‘And so it is during the reign of the Russian Emperor Nicholas the Second, life is terrible for us Poles who groan with the sweat of the Russian rule, the sweat of the Russian whip.’

The letter dated May 9 was written just months after the 1905 Russian Revolution broke out at the start of that year.

At that time Poland officially ceased to exist, having been partitioned between Russia, Prussia and Austria.

But responding to the Tsar’s political, social and economic repressions, Poles had risen up in mass protests, strikes, and demonstrations demanding political freedom, workers’ rights, and national autonomy.

A 120-year-old letter in a bottle offering a snapshot into the hardships of life under the rule of Russia ‘s last Tsar has been found hidden in Poland

Penned in May 1905 by a local blacksmith named Karol Szulc, the ‘time capsule’ letter was discovered during conservation work at the 16th century Benardine monastery in the village of Kazimierz Biskupi

The Tsarist regime responded with brutal repression with Russian troops and police opening on crowds which resulted in hundreds of deaths.

Martial law was imposed and thousands were arrested or deported to Siberia.

Following the collapse of the revolution the regime intensified Russification, censoring the press, closing Polish schools, and cracking down on Polish cultural and political organisations.

In his letter, Szulc also made reference to the-then ongoing war between the Russian empire and Japan, which lasted from February 1904 to September 1905.

He wrote: ‘These are indeed times of war, which Russia is waging with Japan (?), and the war is so terrible that since the beginning of the world there has never been one like it, for in this war already nearly one million people have died, and it is not over yet.’

The conflict – over rival imperial ambitions – ended with a humiliating defeat for Russia, despite its superior strength on paper.

Szulc ended his letter by praising the village’s local priest for building a new church.

He wrote: ‘Yet even in such difficult times, the Lord God inspired with the Holy Spirit our esteemed priest, Father I. Małachowski, who took it upon himself to build a church, and thanks to voluntary contributions, it was completed, rebuilt by the carpenter Michał Nowakowski.’

Tsar Nicholas II survived the 1905 Russian Revolution but had to abdicate in 1917 and was murdered with his wife and children the following year

Builders stumbled across the letter detailing the hardships under Tsar Nicholas II while dismantling a cross on the monastery’s gate tower overlooking the village

The 16th century Benardine monastery in the village of Kazimierz Biskupi, where the bottle was found

Posting the discovery on social media, the mayor of Kazimierz Biskupi, Grzegorz Maciejewski, wrote: ‘A great surprise for all of us.

‘The letter written 120 years ago by our resident Mr. Karol Szulc contains information about the lives of the residents of our town under the Russian partition.

‘This is a truly remarkable historical document.’

The Tsar survived the 1905 uprisings by ceding some of his power and democratising his government.

A constitution issued in 1906 established a parliament – the State Duma – and gave citizens more rights.

But the settlement was short-lived. The Tsar could not withstand the Russian Revolution of 1917, which took place amidst the country’s involvement in the First World War.

He was forced to abdicate and was exiled to Ekaterinburg the with his wife and children.

The entire family were savagely murdered by Vladimir Lenin’s Bolsheviks in July 1918.