This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

When the dome of Florence Cathedral was completed in 1436, it was hailed as the dawning of a new age in architecture — a feat of engineering so incredible that not even the ancients could have matched it. According to Giorgio Vasari, however, it only existed because of an egg.

Until about 20 years before, the dome had seemed almost impossible. Although there were plenty of architects vying to build it, the space it needed to span was so huge that no one could figure out how to make the scaffolding strong enough — no one, that is, until Filippo Brunelleschi came along. Bold as brass, he announced that he had a plan to build the dome without scaffolding. Naturally, everyone wanted to know how. But instead of answering, Brunelleschi suggested they hold a competition.

Whoever could make an egg stand on its end should build the dome. One after another, they tried and failed. Then, when it was Brunelleschi’s turn, he brought it down hard on the table, cracking the bottom and leaving it upright. The others complained that they could have done the same. With a laugh, Brunelleschi replied that they would have known how to build the dome, too, if they’d seen his plans. And just like that, he was given the job.

It is a fanciful story, of course, but revealing nonetheless. Almost from the moment the dome was finished, Brunelleschi’s contemporaries shrouded him in myths. Some, such as Antonio Manetti, cast him as a solitary Renaissance genius, producing architectural miracles in splendid isolation; others preferred to stress his originality. So familiar have these myths become that, even today, it is hard to see Brunelleschi except through the lens they have conjured.

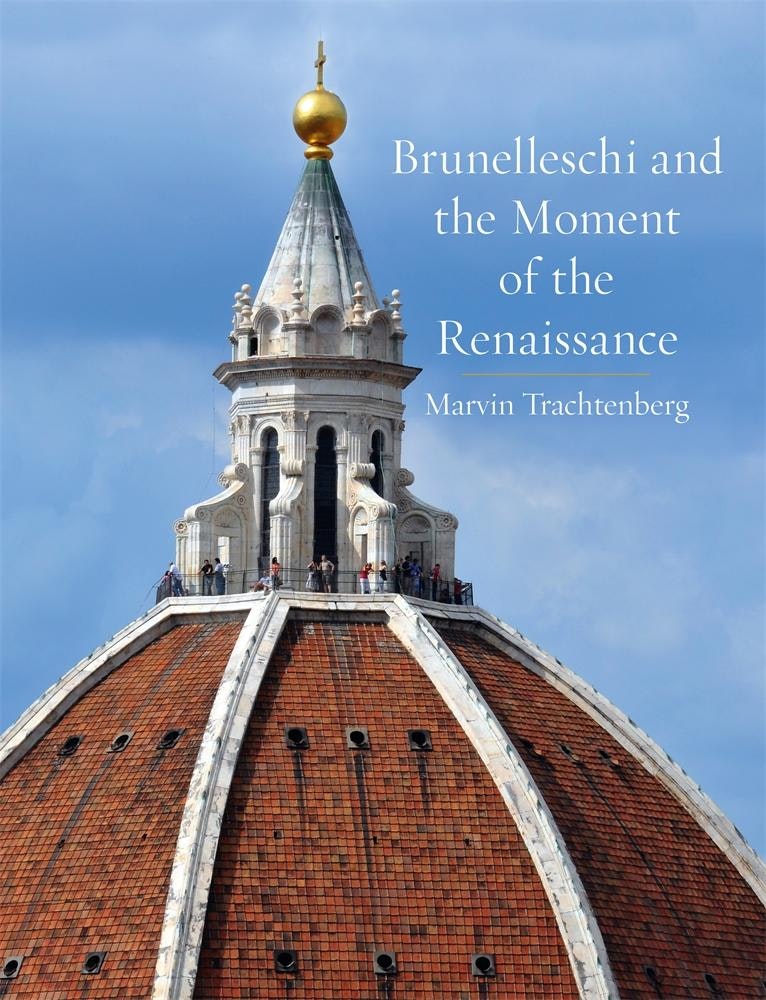

In this striking new book, Marvin Trachtenberg sets out to “demythologise” Brunelleschi. His approach is simple: if we really want to understand him, the key is to look at his buildings themselves. What emerges is a radically different picture. Rather than being a lone innovator, Brunelleschi appears as a more nuanced figure, conscious of his own limitations and open to collaboration.

In Manetti’s telling, Brunelleschi only turned to architecture after he was cheated of victory in a competition against Lorenzo Ghiberti to design a new set of doors for Florence’s Baptistery. As it turns out, however, Brunelleschi was just one of seven competitors — and probably wasn’t even in the running. What was more, Donatello probably helped him with his entry.

So too with the dome. As Trachtenberg shows, Brunelleschi faced a long struggle to get his plan approved — much longer than Vasari’s egg story suggests. In the end, he only won out after seeking advice from mathematician Giovanni dell’Abbaco and agreeing to share responsibility with his old “rival” Ghiberti. That he decided to go into politics at around the same time may have played a part, too.

Even then, he often got things wrong. His design for the Ospedale degli Innocenti — one of Florence’s main orphanages — was praised for its unaffected elegance. Yet its beauty had been gained at the price of practicality. There weren’t nearly enough rooms and since Brunelleschi wouldn’t budge, another architect had to be brought in.

He was eclectic, too. His design for the dome was likely inspired by the Pantheon in Rome, and his works often betray a keen sensitivity for classical modes. But unlike Leon Battista Alberti, who tended to “lift” motifs wholesale from ancient models, Brunelleschi often masked his influences — and paid as close attention to Florence’s Trecento cityscape as to the Roman past.

Yet this, Trachtenberg argues, is precisely what makes Brunelleschi so important. Since he had a foot in both antiquity and the Trecento, he was beholden to neither. He could pick and choose between them as he wished, and he was arguably the first architect to develop his own unique “style”.

Granted, this book is not without its problems. Trachtenberg makes a lot of suppositions and more than a few imaginative leaps. The narrative weaves back and forth, sometimes lingering indulgently over architectural minutiae, sometimes zipping through time at breakneck speed. The decision to omit the Pazzi Chapel, usually regarded as one of Brunelleschi’s masterpieces, is also odd.

This does nothing to detract from the book’s importance. Trachtenberg succeeds in breaking down many of the myths that have blighted our understanding of Brunelleschi and in offering a refreshingly new perspective on his career. Best of all, like Brunelleschi and his egg, he makes it seem easy — and leaves you wondering why no one thought of doing this before.