On the evening of September 25, 1944, a squadron of Lancaster bombers rumbled through the dark autumn clouds above Frankfurt.

Rather than bombs, these engines of war dropped 200,000 packages containing small incendiary devices and cheaply made pistols.

It was hoped that the weapons would land behind the barbed wire fences of the forced labour and prisoner of war camps on the city’s outskirts.

Fourth months after the beaches of Normandy were stormed by Allied troops, this airdrop – codenamed Operation Braddock – was meant to hasten the Third Reich’s end.

Instead, this ambitious effort to arm Germany‘s enemies within stands as a testament to the great expectations and limited realities of innovation in war and determination in the struggle to defeat Nazism.

The mission to Frankfurt was one of several airdrops that comprised Operation Braddock, the aim of which was to encourage a wave of mass sabotage and panic across the Third Reich.

The idea first emerged from the fertile imaginations of the Special Operations Executive (SOE) – the irregular warfare department established by Winston Churchill in 1940 with the mission to ‘set Europe ablaze’.

In 1943, the Minister in charge of SOE, Lord Selbourne, chose to interpret this order literally.

An example of ‘Liberator’ pistols that were designed to fire one bullet and then be reloaded. They were made to be dropped behind enemy lines to foment rebellion

British four-engine Avro Lancaster Mk strategic bombers of the 207th Bomber Squadron of Bomber Command of the Royal Air Force

Under his direction and with the support of the American SOE equivalent, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), a plan was developed to manufacture small grenades filled with explosive gel.

These could be easily activated by the user pressing an external firing pin, which would set the device on a timer to ignite between 15 minutes and several hours later.

Millions of these grenades – dubbed ‘Braddocks’ – were manufactured into 1944.

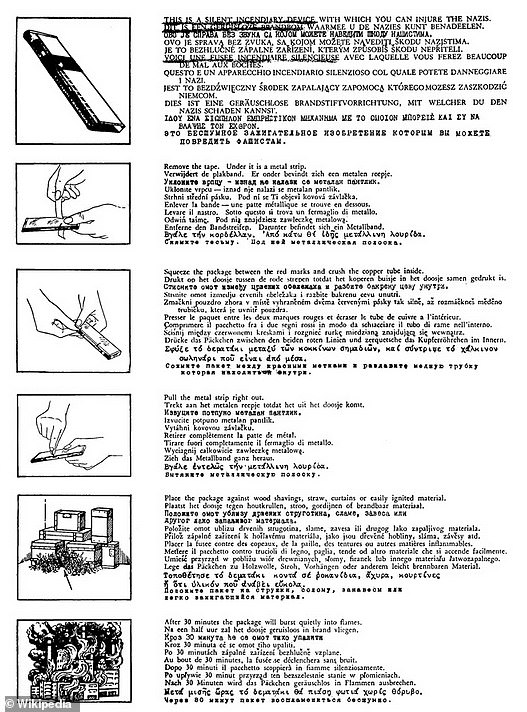

Each Braddock was then packed into a cylindrical case with a card-sized instruction manual, printed in a dozen European languages, alongside an American-made single-shot Liberator pistol.

The resulting kit was cheap to produce, geared to violence and easy for the untrained to use.

Amidst planning for the June 1944 D-Day landings, Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower offered his support for Operation Braddock.

He saw the arming of prisoners via airdrop as a means of creating chaos behind German lines once Allied boots landed on French soil.

It was at this point, however, that snags appeared in the plan. Royal Air Force chiefs balked at the idea of using precious bomber crews and cargo space to deliver crude weapons rather than building-shattering bombs to the Reich.

Instructions for starting fires that were produced to be dropped into Germany

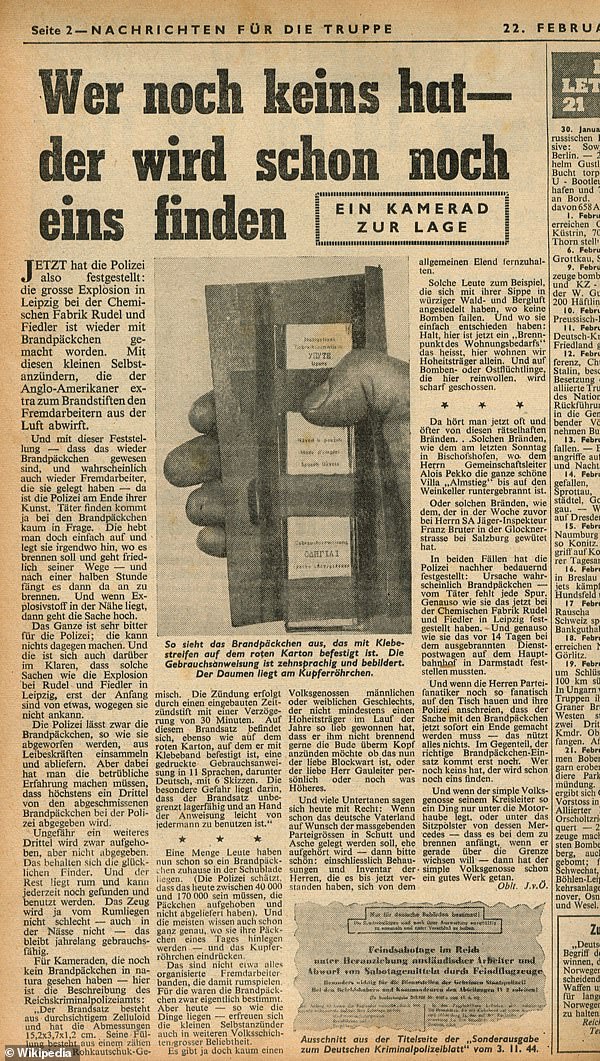

A German-language fake newspaper, produced by the Allies

Concern was also voiced about the consequences those who took up the challenge of using the Braddocks might face from the German security forces.

The head of the Political Warfare Executive (PWE) – Robert Bruce Lockhart – was one such dissenter.

Lockhart had seen the bloody retribution dealt to anti-authoritarian agitators in the Soviet Union during his time as a spy and diplomat in Moscow at the end of the First World War.

He was also mindful that another brazen SOE scheme – Operation Anthropoid, the 1942 plan to assassinate the Reich Protector of Bohemia and Moravia, Reinhard Heydrich – had led to the murder and detention of thousands of Czech civilians and the brutal destruction by the Schutzstaffel (SS) of an entire village.

This fear of mass reprisals was further brought home to Lockhart when one of his subordinates casually concluded that during Operation Braddock, ‘many foreign workers might be killed’.

As the man tasked with waging Britain’s psychological warfare effort against the Third Reich – a key component of which was ‘marketing’ the Allied cause to occupied Europe – Lockhart was also concerned that Operation Braddock might be interpreted by Europe’s oppressed as the British and Americans getting emaciated prisoners to do their fighting for them.

To square the circle of Lockhart and others’ concerns, over the summer of 1944, Operation Braddock morphed into more of a psychological warfare operation.

With the air force’s wary agreement, the number of Braddocks dropped over the Reich would be reduced.

Robert Bruce Lockhart, the head of the Political Warfare Executive

The deficit of impact was to be made up for by PWE broadcasting propaganda into the Reich to exaggerate the Braddocks’ effect.

In the hours after the incendiaries were dropped on the outskirts of Frankfurt in September 1944, PWE used fake radio stations broadcasting from the Bedfordshire countryside into Germany to wreak havoc.

Under the guise of being Nazi-controlled propaganda radio, they informed the German public that thousands of mysterious fires were raging across the region.

Fed by intelligence assets on the ground, PWE broadcasters even distorted the story of a factory worker in Mainz being killed in an accident to suggest that a Braddock fire was to blame.

In taking this approach, PWE were following a classic dictum of psychological warfare – building a big lie from a kernel of truth.

The fact was that some of the Braddocks did reach their intended targets and those prisoners and resistance fighters did set fire to German barracks, communications and railway stations.

None of this was on a scale to match the original ambition of creating mass disruption behind German lines.

However, owing to PWE’s injection of fake news-driven fear into the operation, the Gestapo and the SS did commit resources to confiscating Braddocks and chasing after phantom saboteurs, increasing anxiety and sapping morale at a crucial moment in Germany’s war effort.

The last known picture of Adolf Hitler, taken outside his bunker in Berlin shortly before he killed himself

In this sense, PWE contributed to the wider allied war effort to destroy Nazi Germany.

This reached its climax in the spring of 1945, when Russian troops entered a bomb-battered Berlin defended by exhausted soldiers, old men and Hitler Youth.

By then, the Fuhrer had retreated to his bunker under the Chancellery building, where he ended his life on April 30, as the Reich he thought would last a thousand years crumbled around him.

As we commemorate the 80th anniversary of the Second World War’s end, Operation Braddock provides an excellent example of the innovative lengths to which irregular forces like PWE, SOE and the OSS were prepared to go to defeat Hitler.

James Crossland is the author of Rogue Agent From Secret Plots to Psychological Warfare, The Untold Story of Robert Bruce Lockhart (Elliott & Thompson), out July in paperback, £10.99.