Brazil’s bottleneck for industrial excellence.

Brazil, the South American giant known for its rich culture, vast natural resources, and early industrial ambitions, has long prided itself on building an industrial base that spans everything from soaps to aircraft. Many credit this growth to protectionist policies: high tariffs on imports, tax breaks for domestic producers, and generous government incentives. But beneath that narrative lies a different story—one of inefficiency, lost potential, and costly failures. Instead of accelerating Brazil’s rise, protectionism has often held it back, creating an industry dependent on political favors rather than market performance.

Brazil’s experiment with incentivizing its automotive sector began as early as 1919, when Ford became the first automaker to assemble vehicles in the country. The American company was drawn by a generous package of tax breaks and import protections, enjoying broad tax exemptions on imported capital goods and higher tariffs on competing vehicles imported from abroad. These measures were extended to other firms like GM and Romi. But from the start, these incentives distorted rather than developed the market.

The most infamous early failure? Fordlândia. Built in the 1920s as a self-contained industrial city deep in the Amazon, it was intended to supply Ford’s rubber needs. But it collapsed within two decades, thanks to tropical diseases, poor planning, and cultural arrogance. Ford lost the modern equivalent of $170 million solely on capital goods, while total losses, including labor, capital costs, and unusable inputs, remain uncertain. The project didn’t fail because the idea was flawed, but because it was insulated from competitive pressure and real-world feedback.

In the 1950s, President Juscelino Kubitschek made industrialization through protectionism Brazil’s official doctrine. His Plano de Metas banned imported vehicles and demanded that carmakers localize production in exchange for tax incentives. Automakers like Volkswagen and GM rushed in, not because Brazil was the best place to make cars, but because it was one of the few places they were guaranteed to sell them. Between 1956 and 1961, three decrees were issued offering special fiscal and strategic incentives to companies that committed to domestic production. This strategy was part of a broader regional trend known as Import Substitution Industrialization (ISI), which aimed to reduce dependency on foreign goods by building up domestic industries behind high tariff walls. While it spurred rapid industrial growth in the short term, ISI often led to inefficient, uncompetitive sectors protected from global competition, ultimately burdening consumers with higher prices and fewer choices.

By the 1970s, Brazil had built a sprawling auto industry that employed hundreds of thousands. But there was a catch: without foreign competition, there was little reason to innovate or cut costs. Brazilian consumers paid the price, literally. By 2025, the average Toyota Corolla hybrid cost over $13,000 more in Brazil than in Mexico, being 18% less cost-effective. Even though Brazilian engineers developed flex-fuel engines, the sector as a whole lagged in quality and innovation.

Over time, Brazil’s protectionist model became not just inefficient but unsustainable. Policymakers responded by doubling down. Programs like Rota 2030 offered tax breaks for hitting vague production targets or local content quotas. These policies propped up the industry temporarily, but failed to prepare it for real competition. Decades of protection did not turn into global competitiveness. Brazil’s automakers serve the home market well, but struggle to export. At its 2013 production peak of 3.7 million vehicles a year, Brazil only exported around 15% of that output—their top automotors trading partners being Argentina, Mexico, Colombia, Uruguay, and Chile.

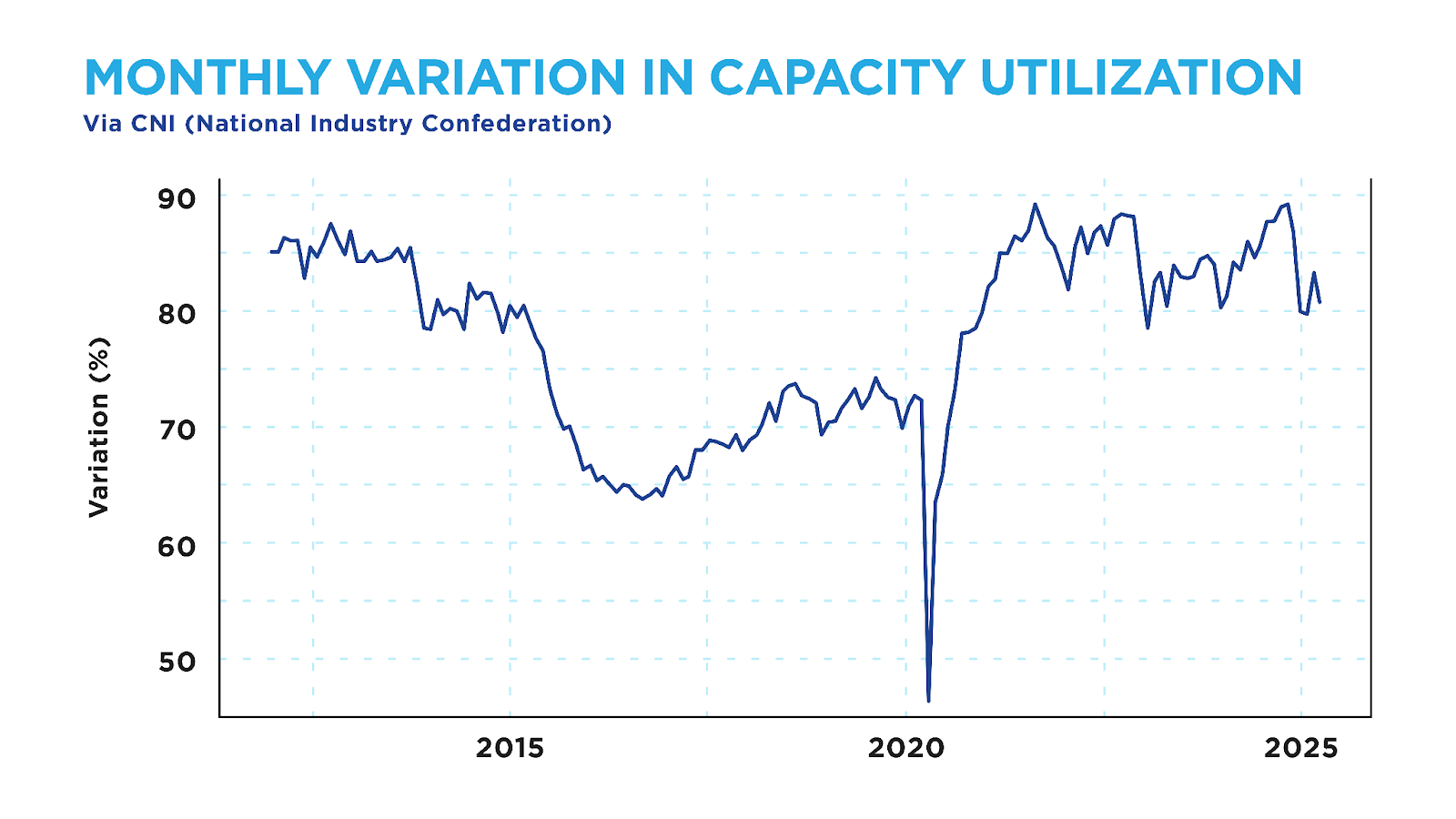

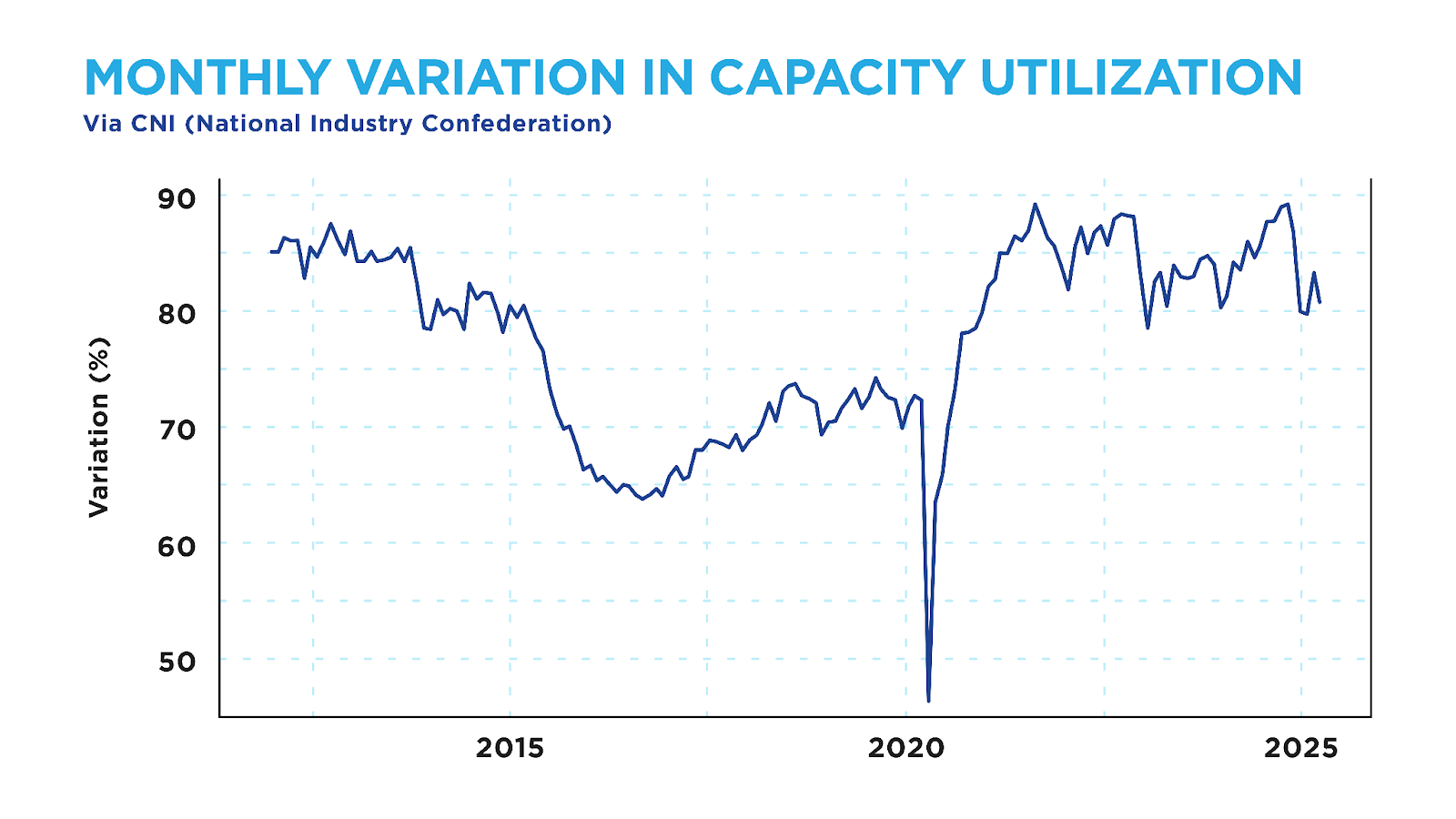

Most Brazilian plants are not cost-competitive enough to ship cars to Europe or Asia in large numbers. Eventually, when Brazil’s economy slowed in the 2010s due to a combination of falling commodity prices, political instability, and unsustainable public spending, production tanked, and global giants like Ford started to close plants and even to cease operations completely.

The exit of Ford in 2021 was symbolic. After more than a century in Brazil, the company couldn’t justify staying, not without fresh subsidies. By that time, Ford had endured a decade of severe underutilization and an inability to cover fixed costs without subsidies from its US parent. In 2023, however, Ford signaled it might return to Brazil, after President Lula da Silva hinted at offering major strategic advantages to electric vehicle makers setting up here. Once again, the industry turned not to innovation or exports, but to the government for rescue.

Brazil still exports only a fraction of its vehicle output—mostly to its neighbor Argentina, under managed trade agreements within Mercosur. Meanwhile, Mexico chose a more open path. After signing NAFTA in 1994, it slashed tariffs, welcomed foreign investors, and focused on becoming an export platform. Today, Mexican plants produce more cars at lower cost and higher quality than Brazil, despite lacking a major domestic automaker. The difference? Competition. Mexican factories serve global markets. Brazilian ones serve a protected domestic market, at a cost to consumers and productivity.

Perhaps the most sobering lesson from Brazil’s experience is how incentives, when misused, can entrench dysfunction. State subsidies distorted logistics: Brazil built highways instead of railways, even though water transport would have been cheaper for many regions. The heyday of auto-industry influence in Brasília coincided with Brazil’s most transformative decade of infrastructure development, and predictably skewed investments toward highways over rail, waterways, and air transport. Those choices have left a lasting mark: even today, roughly 86% of consumer goods and 74% of capital goods in Brazil are moved by truck, compared with a mere 5% and 8% via waterways, despite Brazil’s 7,357 km coastline and rivers covering 12% of the world’s freshwater surface.

Even now, when new policies like Rota 2030 aim to focus on innovation, results have been modest. Cars may have better fuel efficiency and safety features, but the sector is still far from becoming globally competitive.

Industrial policy can nurture an infant industry, but when that industry becomes dependent on state favors, it fails to mature. Brazil’s automotive sector was born behind walls and grew fat on subsidies. But now, with liberalization on the horizon, set to phase out auto tariffs in the coming years, the industry must either adapt or collapse. Like the Mercosur–EU trade deal, which set an agreement between South America’s largest trading bloc and the European Union that aims to eliminate tariffs and open markets gradually over the coming years.

Fordlândia remains a ghost town in the Amazon. But it’s also a metaphor: vision without feedback is fantasy; protection without pressure is stagnation. Brazil’s automotive sector must stop chasing the next incentive, and start competing. Otherwise, the dream of industrial greatness will remain just that: a dream, rusting in the jungle.