In an article in the Journal of Public Finance and Public Choice, I challenge this assumption insofar as it pertains to modern public health campaigners. The very existence of single-issue pressure groups dedicated to wholly paternalistic action to stop other people consuming tobacco, vapes, alcohol, sugary drinks and certain foods should pose a challenge to public choice economists. Not only have they overcome the free rider problem that deters individuals from joining groups to fight for collective benefits, but they do not appear to have any collective benefits to fight for in the first place. On the face of it, they will not be any better off if they succeed in their campaigns. Given this apparently irrational behaviour, economists have been quick to accept that moral fervour is sufficient explanation. I am not so sure.

One possible explanation for the existence of paternalistic pressure groups is that, if you dig a little deeper, they are fighting for collective benefits. The activists themselves sometimes argue that their political activity is not wholly paternalistic because they are trying to save the NHS money. They argue that smoking, drinking and obesity create external costs that hit the taxpayer. Such claims do not stack up when a full cost-benefit analysis is conducted, but they are nevertheless widely believed and so it is possible that a group of citizens would take collective action against people with bad habits to save themselves money.

But even if the externality claims were true, the financial benefits of suppression would be spread very thinly over the entire population and would be miniscule to the individual. As Mancur Olson famously observed, the costs to the individual of joining or donating to a pressure group aimed at deterring smoking or over-eating would almost certainly exceed the potential reward and even if they did not, the free rider problem would still exist. Olson’s main insight was that people do not take collective action to fight for relatively small gains that are widely dispersed. There is no reason why his theory should not apply here.

A second possible explanation is that paternalistic campaign groups overcome the free rider problem by offering selective incentives to their members, such as price discounts and networking events. This is certainly true of some of the organisations that lobby for lifestyle regulation as a sideline. The British Medical Association (a trade union), the Salvation Army (a religious group) and the Royal College of Physicians (an elite association for medical professionals) offer social and often financial benefits to members which have nothing to do with their lobbying against alcohol, for example. Having attracted resources by other means, they are free to engage in political activity that is not directly related to their core purpose.

But this does not apply to the small, concentrated pressure groups that focus solely on single-issue campaigns. In the UK, the most prominent of these in recent years have been Action on Smoking and Health (ASH), ASH Wales, ASH Scotland, Alcohol Focus Scotland, Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Problems (SHAAP), the Institute of Alcohol Studies, Alcohol Change UK, Obesity Action Scotland, the Children’s Food Campaign and Consensus Action on Salt, Sugar and Health (CASSH) (AKA Action on Sugar). These pressure groups not only fail to offer selective benefits to their members but are not membership organisations at all.

The third possibility is that these groups are essentially philanthropic, i.e. other-regarding, and require no further explanation. In this view, the anti-smoking campaigner is no different from the anti-war demonstrator, and the person who donates to an anti-sugar pressure group is driven by the same incentives as the person who donates to the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds.

There are several reasons to question this. Firstly, coercive paternalism is objectively not altruistic. Unless there is clear evidence of market failure, economists assume that people satisfy their preferences and optimise their wellbeing. Anything that stands between them and their small pleasures imposes a cost on them and makes them less happy. This is hardly altruistic. Admittedly, paternalists may not share the assumptions of economists, but the general public does not seem to be view coercive paternalism as altruistic either. The British donate large sums of money to such causes as animal welfare and disaster relief, but they almost never donate to paternalistic pressure groups and there is virtually no voluntary activism against drinking, vaping, gambling and so on.

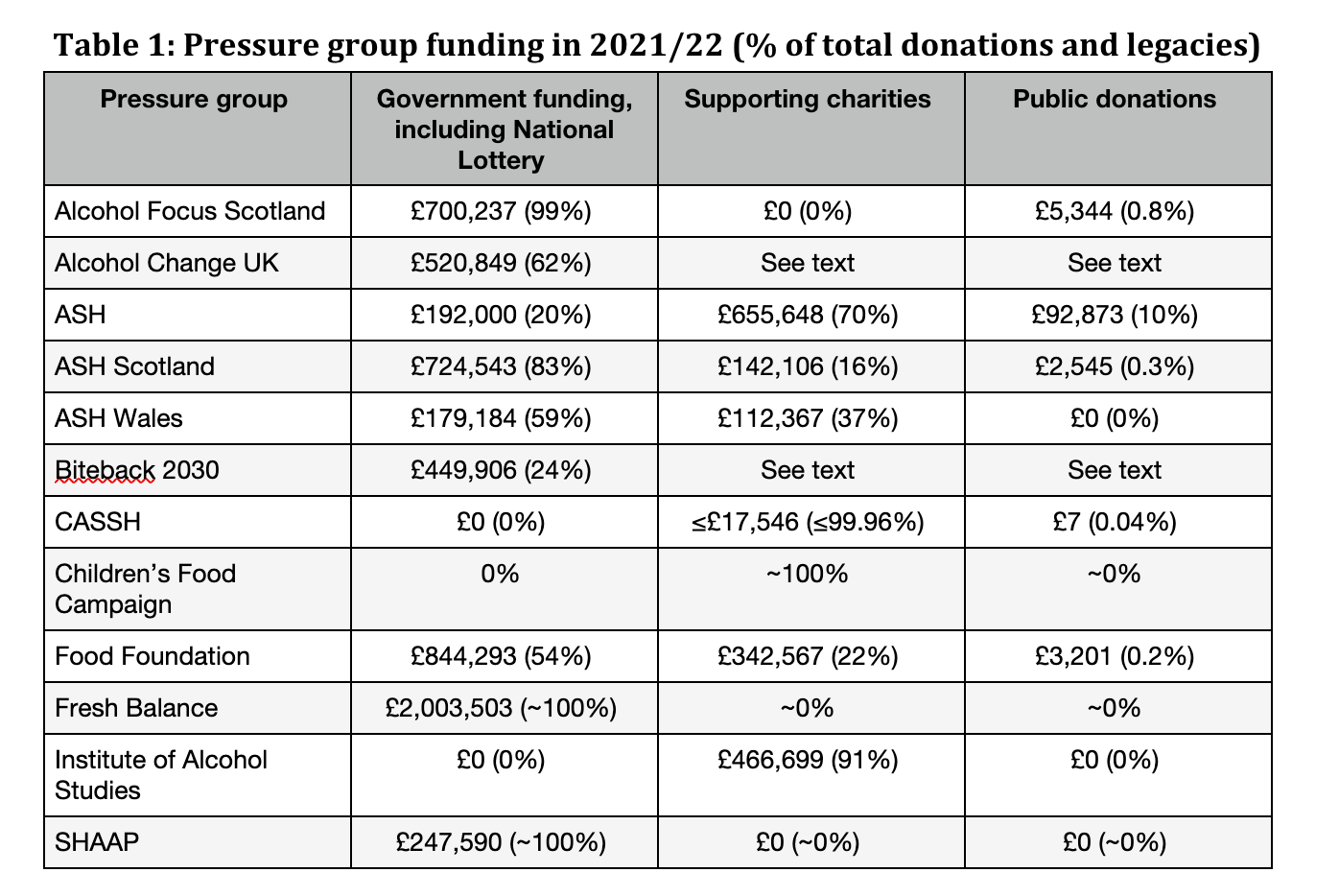

Finally, altruism by definition requires selflessness. If an individual benefits from an action, it is not altruistic. But the UK’s single-issue public health pressure groups consist of a very small number of people who are fully remunerated for their work. As shown in the table below, they do not depend on donations from the public but from elite sources, mostly the government. Most of the groups in the table receive less than 1% of their income from the public. There is no need for them to offer selective incentives because they only have a small number of employees who are financially incentivised by their salaries. They bypass the free rider problem by having no members and by acquiring their resources from a tiny number of state and third sector actors. I discuss in the paper the reasons why the government, a few large charities and the occasional super-rich donor give money to these groups, but the important point is that these groups would probably not exist without this funding and the ‘activists’ are being paid for their activism. They are, in short, acting in their narrow economic self-interest.

One implication of this kind of professionalised, state-funded activism is that it creates a permanent imbalance in the political ecosystem. As Olson argued, vociferous minorities can prevail over unorganised majorities so long as they have the resources and incentives to do so. Consumers do not mobilise to defend their collective interests for the reasons Olson explained. It is well known that the demands of pressure groups can become increasingly extreme over time (‘mission creep’), but this becomes almost inevitable when people are being paid to campaign. The big difference between the single-issue pressure groups described above and the typical public or private interest group is that the former exists only to campaign for new policies. It almost doesn’t matter what the policies are.

Society in general may be content with a new equilibrium, but a permanent settlement is an existential threat to the professional pressure group. So long as they are given the resources, they will continue to find new dragons to slay. Indeed, they must find new dragons to slay if they are to continue attracting resources. Permanent disequilibrium is built into the business model.

Taken to its logical conclusion, this would lead to lifestyle regulation in the name of public health becoming a one-way ratchet that leads to increasingly draconian measures being enacted. Further research in other countries is needed to see whether this theory of paternalistic collective action is generalisable, but it could certainly explain what has been happening in Britain in recent decades.