This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

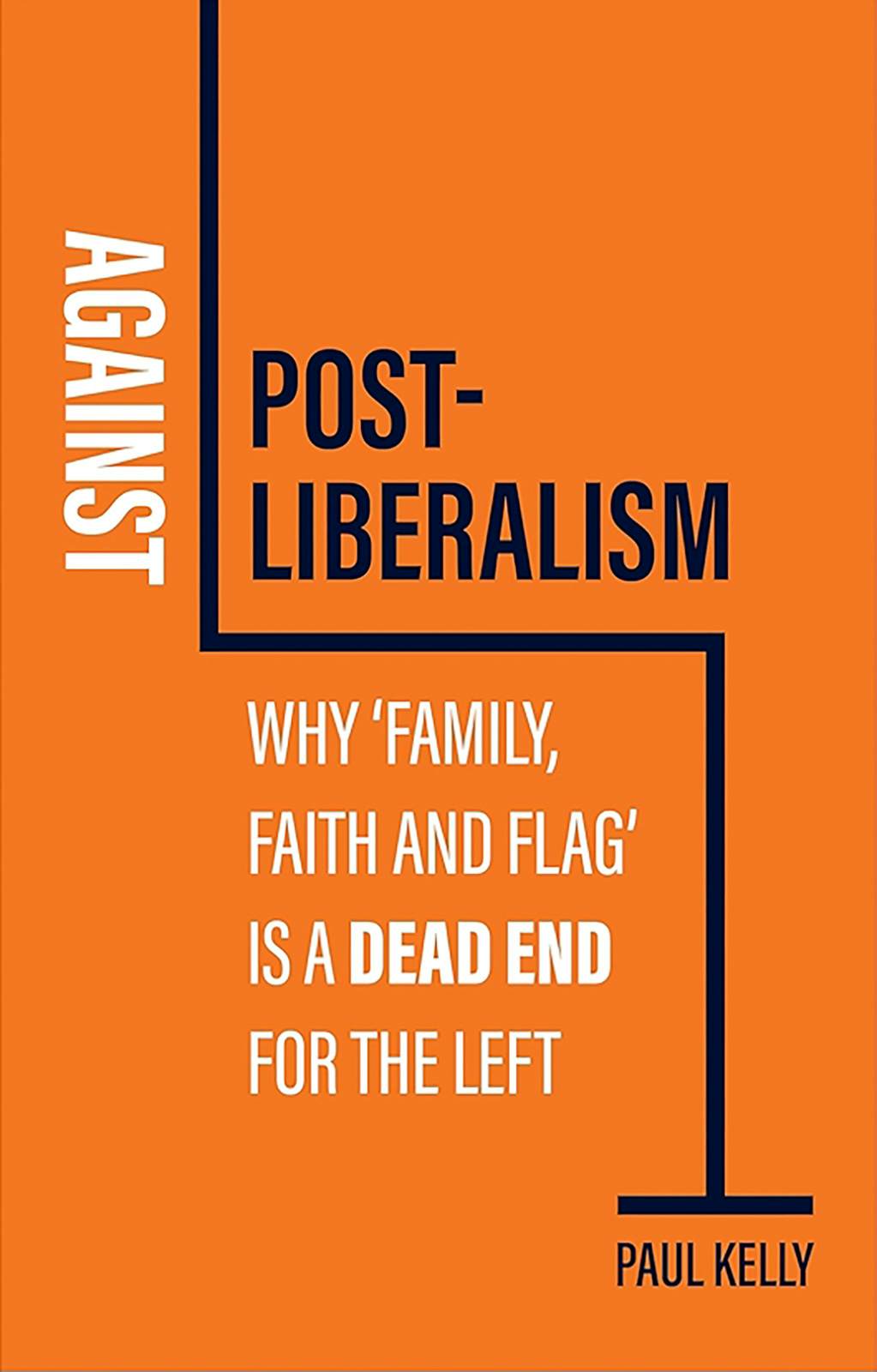

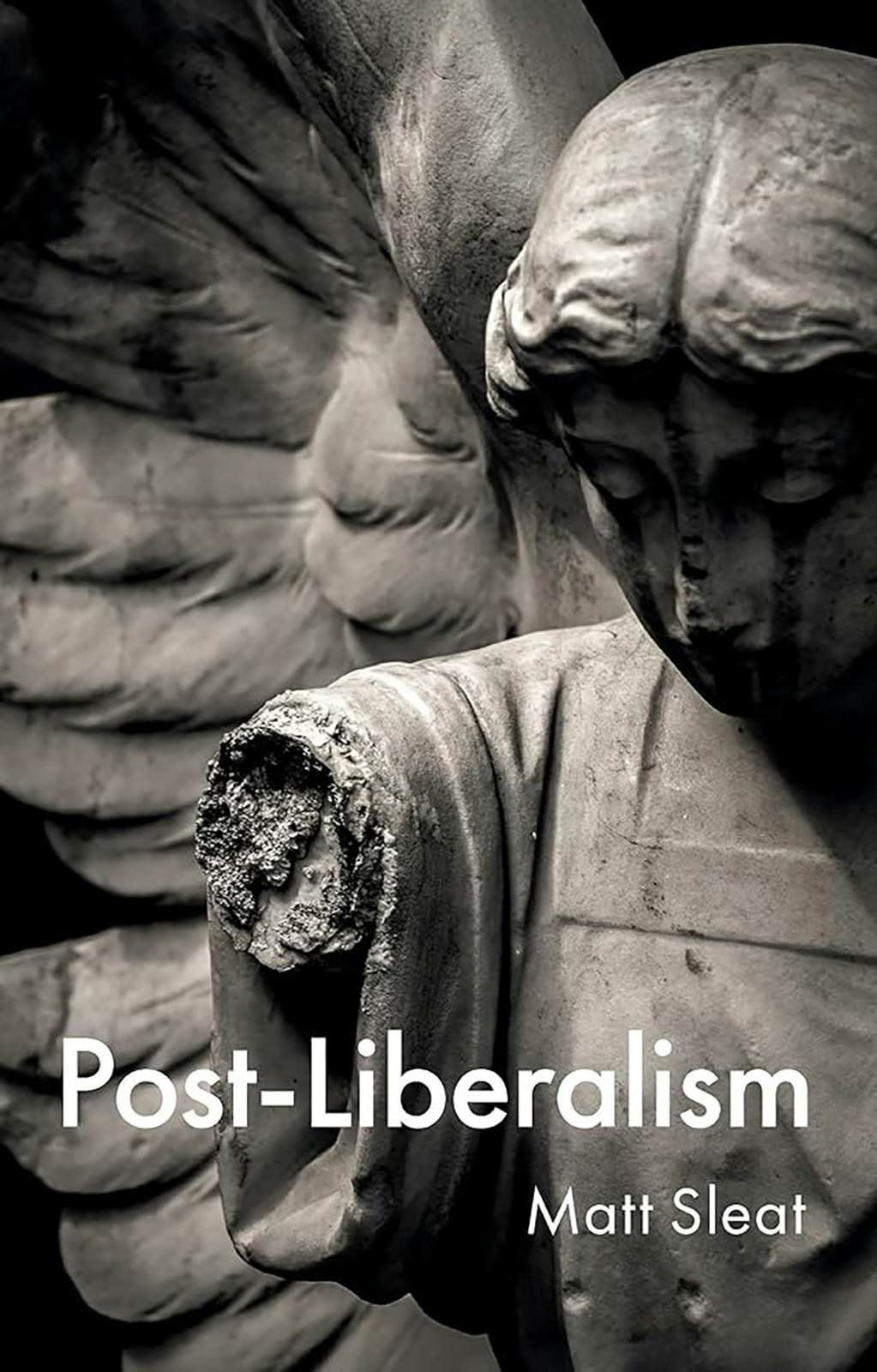

You know that something is really having an impact the moment people start writing books to criticise it. Post-liberalism has now prompted not one but two books, at the same time and from the same press, to make the case against it. Make of that what you will. Post-liberalism is certainly hitting its stride: both of these books make clear that they were motivated, in part, by the elevation of J.D. Vance to the position of US vice president, which unequivocally marks post-liberalism’s move to the mainstream.

But what exactly is post-liberalism, and where is it taking us? Both Paul Kelly, Professor of Political Theory at LSE, and Matt Sleat, Reader in Political Theory at the University of Sheffield, seek to answer these questions by unravelling the tangled narratives of post-liberalism. Each charts the movement’s intellectual diversity through its most famous figures, taking in Alasdair MacIntyre, John Gray, Maurice Glasman, Matthew Goodwin, Danny Kruger, Patrick Deneen and Adrian Vermeule — these last two receiving particular attention, no doubt thanks to the Vance factor.

Despite their stated opposition to post-liberalism, both authors describe its character correctly — and fairly. Fundamentally, political liberals — in their conviction that individuals merely sought freedom from ideology to live as autonomous, pleasure-seeking beings — overlooked the profound sense of boredom, disconnection and spiritual disorientation that their worldview inadvertently fostered. Yet despite the hyper-individualism of the modern world, people still yearn for something to believe in, which makes their hunger for collective identity as strong as ever.

The deracination of private life, public man and communities of belonging left people searching for something — anything — to fill the void. Liberalism became the weapon of its own demise; it was no longer sufficient to enjoy personal freedoms without also being affirmed as part of a group endowed with special protections. The fight against racism has shifted from a call for equal treatment to a push for preferential policies that favour select minorities.

The explosion and expansion of identity-based movements reflect not just a quest for recognition and resources, but a therapeutic need for belonging. For many, the pursuit of autonomy has led to an unsettling sense of anomie, a void where a coherent self should be. In this vacuum, solidarity with perceived victims offers a surrogate purpose, and identity is forged not through introspection, but through immersion in the fervour of collective causes.

Confronted now with the magnitude of this oversight, political liberals have found themselves jolted into a new reality, one marked by rebellion and renewal. Across the globe, people are captivated by the possibility that politics may once again infuse life with shared meaning, direction and a sense of collective destiny. Post-liberalism provides just that: a story not only of where we are and how we got here, but also of where we should be going.

Yet it is a movement that, so far, has mostly been characterised by ideological bickering and intellectual foppery. Post-liberalism carries so many strains of thought at once: anti-modern traditionalism, Catholic integralism, Nietzschean elitism, Anglofuturism, left-conservatism, majoritarian populism and executive aggrandisement, just for starters.

Sleat and Kelly attempt to chart a coherent course through such a farrago. Both strive for the same end — a rejection of a post-liberal society, whatever that may look like. Kelly tacks towards explaining why post-liberalism is a mistake for the left in particular, and adopts a more condemnatory style; Sleat’s jibes reveal a more dispassionate approach, evidently motivated by the need to defend some form of liberalism.

However, it is not post-liberalism’s critique of liberalism that presents the biggest challenges, but its indecision on where it is taking us, or how — a lacuna of practical political application which neither Sleat nor Kelly explore to its full extent.

Post-liberalism’s greatest failure is, and always has been, its inability to step from the realm of prose into policy. Now it’s high time that post-liberals started: of the foundational texts, Philip Blond’s Red Tory is nearly 15 years old, Patrick Deneen’s Why Liberalism Failed is eight years old, and David Goodhart’s The Road to Somewhere a year older.

As Sleat notes, “We do not need to be strict materialists to recognise that history is shaped by more than just ideas.” Post-liberals have, so far, been largely unable to come up with an idea of rights or responsibilities beyond those which are arbitrated by the state — i.e. through central government provision and taxation. For so much intellectual effort, defining the “bonds of community” solely through the tax take is a poor return.

Yet this lack of a positive project belies post-liberalism’s real goal, correctly identified by Kelly: if it is the overthrow of the liberal hegemonic discourse via “a counter-hegemony to displace it, which is achieved by taking control of the dominant institutions of the political, social and economic culture of a society”, then post-liberalism’s focus on establishing narrative dominance first and foremost makes more sense.

This post-liberal desire to establish narrative control lays a trap for both authors, from which neither emerge unscathed; in order to challenge post-liberal thinkers, Sleat and Kelly must implicitly accept their framing. As an alternative, they offer a coherent set of liberal remedies to the sociopolitical concerns that post-liberals deem urgent — but those concerns misdiagnose the true nature of our present crises.

John Gray wrote in the New Statesman recently to disavow his post-liberalism, arguing that hyper-individuality has not, as post-liberals predicted, resulted in a world full of autonomous, pleasure-seeking beings, but rather the development of exclusory and separate communities along communal lines, with an underpowered state unable to prevent “catastrophic breaches in civil peace”, including the industrial scale and ethnically targeted rapes of white working-class girls, expulsion of Christians from their professions, attacks on Jews when they practise their faith, and rising animosity towards immigrants.

Carl Schmitt is cited heavily by both these authors. That is understandable, since in the conditions Gray describes, Schmitt would emerge as a prophet: the politics of the “common good” would be discarded entirely, replaced by a ruthless calculus of “good for whom”.

Given the reality of our civilisational circumstances, post-liberalism comes across as at best an abstraction, and at worst moral evasion: a way of talking around the consequences of liberalism’s failure, rather than work through them. The way through, Gray posits, is for the Leviathan to rear its head and limit the authority of communities rather than reinforcing their boundaries:

If what Hobbes called “commodious living” cannot be reinvented by a strong state, our future will be a war of all against all, fought out not between individuals but identity groups — a life that might not be solitary or necessarily short, but will be nasty, brutish and certainly poor.