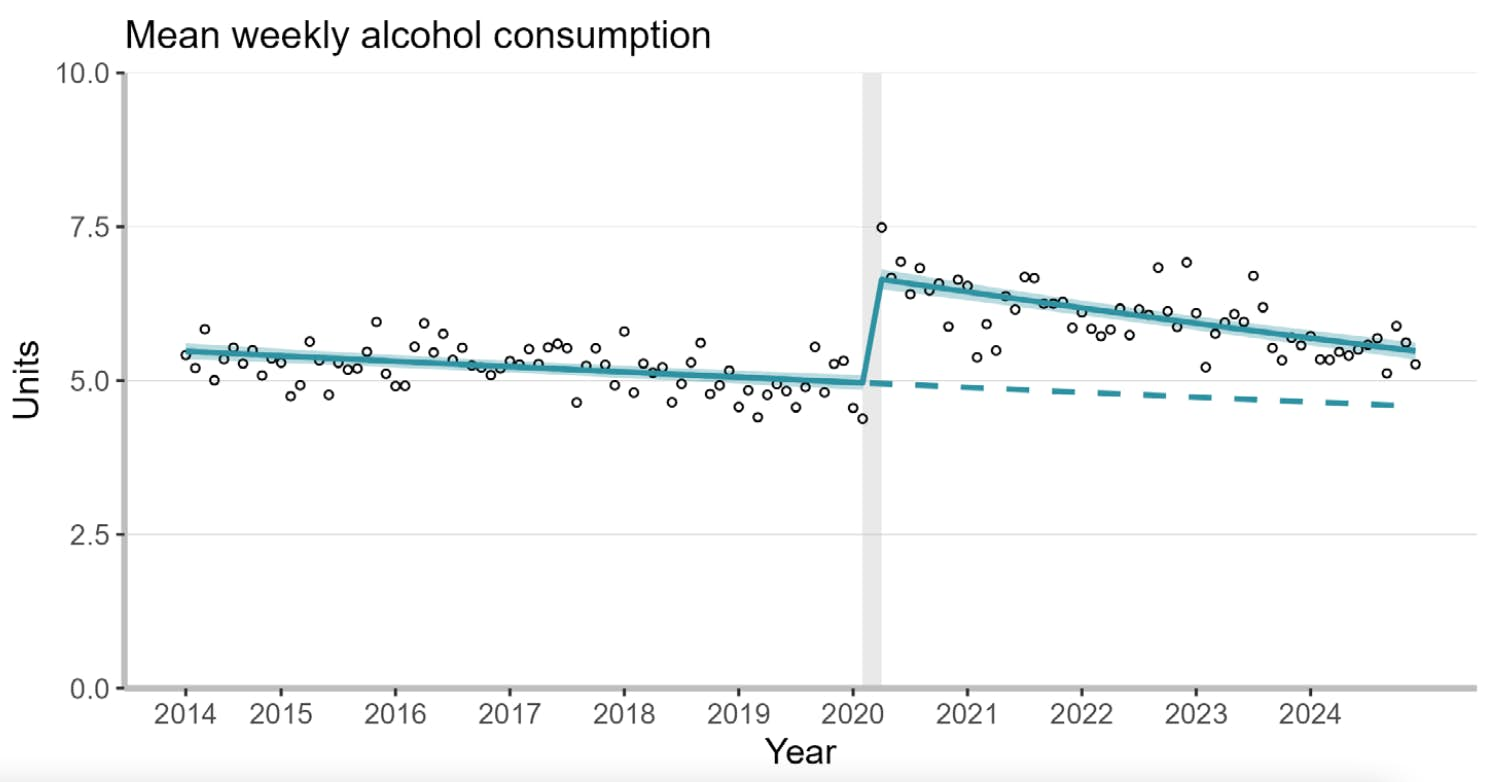

Some things are so absurd that only a public health academic could believe them, as George Orwell so nearly said. A study published last week claimed that people living in England increased their alcohol consumption by 34.5 per cent between February and April 2020 and spent the next five years drinking more than they did before the pandemic. Their data are presented below.

This will come as news to the drinks industry, the pub trade and anyone who holds shares in either of them. The prevailing narrative about booze, both in Britain and worldwide, is that it is on its way out, or at least in decline, thanks to teetotal Gen Zers and clean living millennials. Sales of wine in major markets fell by 9 per cent last year. Britain has lost 12,000 pubs since 2007 and, despite the rise of craft beer, beer sales have been falling for decades. According to the British Beer and Pub Association, beer sales were 38 per cent lower in 2021 than they were in 2019. The gin bubble has burst and the main growth area in the spirits sector is in drinks that contain no alcohol.

How can this be if alcohol consumption rose by more than a third during lockdown and is yet to return to pre-pandemic levels? The answer is simple: the study is complete wibble. Rather than look at sales figures, the authors relied on surveys. People are notoriously unreliable narrators when it comes to reporting their alcohol intake. If we relied on survey evidence, we would have to assume that half the alcohol sold in Britain is poured down the drain.

But this survey has a special flaw that makes it even worse than usual. The Alcohol Toolkit Study, upon which the researchers rely, used to be conducted face-to-face. That wasn’t possible due to social distancing measures in March 2020 and so no data is available for that month. When the survey returned in April, it was conducted by telephone and, as the authors note, “higher proportions of the face-to-face sample reported never drinking alcohol and never having six or more standard drinks on one occasion compared with the telephone sample”. You might think that this renders any before-and-after comparison worthless, and you would be right, but the authors plough on, conducting an “unplanned sensitivity analysis” in an attempt to control for under-reporting in the pre-pandemic period. After making adjustments, they conclude that the “real” increase in alcohol consumption in the early days of lockdown was 19.6 per cent.

That would still be a massive spike in the nation’s drinking habits and it would still defy belief. Where was everyone buying all this extra booze? Were they making it themselves? Alcohol tax receipts only increased by 2 per cent between 2019/20 and 2020/21 and that was only because there was a shift from relatively low-taxed beer and cider to highly taxed wine and spirits. On a per-unit basis, the sale of alcohol fell in the first year of the pandemic. We can argue about exactly how much it fell, but it did not rise and it certainly didn’t rise by 20 per cent.

Data from Public Health England show that despite a £200 million increase in alcohol tax revenue, overall alcohol consumption fell by 1.2 per cent in 2020/21. Retail data from Nielsen shows that the volume of pure alcohol sold fell by 4 per cent per adult in 2020. A study published in 2021 found that the amount of alcohol sold between 15 March and 11 July 2020 was 6 per cent lower than usual for that time of year. And a study published the following year reported that adults in England bought an average of 16.5 units of alcohol per week before lockdown, which dropped to 13.7 units during lockdown, and remained below the pre-lockdown level for the rest of 2020 (and notice how much higher these figures are than the self-reported figures in the graph above!).

Unless people were making industrial quantities of gin in their bath tubs (very unlikely) or buying a vast amount of duty-free booze (even more unlikely given the lockdowns and travel restrictions), the data showing how much alcohol was actually sold should be taken more seriously than a telephone survey if we want to know how much we were drinking during the pandemic. That is especially true when you are faced with what the authors describe as the “unavoidable limitation” that “the data collection mode changed when the pandemic started”. They say themselves that: “People seem to report lower alcohol consumption in face-to-face compared to telephone interviews, with the exact magnitude of the mode effect being uncertain”. The obvious way to ascertain the exact magnitude would be to compare what people self-report to what they buy, but the authors do not even mention the sales data and — surprisingly in an academic study — they do not discuss the existing literature. Instead, they essentially use guesswork to adjust data that is irredeemable.

The belief that per capita alcohol consumption and alcohol-related deaths must rise and fall in lockstep is sacrosanct in “public health” academia

After acknowledging the “unavoidable limitation” of their research, they try to salvage it by saying: “However, rising alcohol-specific mortality rates since the pandemic started provide face validity for increases in consumption”. This gets to the heart of it. The belief that per capita alcohol consumption and alcohol-related deaths must rise and fall in lockstep is sacrosanct in “public health” academia. This theory was reverse engineered to justify reducing the affordability, accessibility and advertising of alcohol, policies that do nothing to help alcoholics but could, in theory, reduce overall consumption. What happened during the pandemic was a good example of the theory failing. Overall consumption fell slightly and drinking patterns became polarised, with social drinkers consuming less and some heavy drinkers consuming more. Because of the latter — who couldn’t access treatment services during lockdown — there was a sharp rise in alcohol-specific deaths which shouldn’t have happened if you believe in the total consumption model.

Rather than ditch the theory, the authors of the new study use the rise in deaths as prima facie evidence that total consumption went up when it didn’t. This is where dogma takes you. It comes as no surprise when they conclude by saying that “new alcohol control policies with a focus on narrowing inequalities are required to reduce alcohol-related harm in Great Britain, such as those to reduce the affordability, accessibility and advertising of alcohol”. Ideologically, this is all perfectly consistent, and when a fellow believer wants to claim that alcohol-related deaths rose in 2020 because per capita alcohol consumption went up, they now have a peer-reviewed study to cite. The fact that it is obviously and demonstrably nonsense is neither here nor there.