This article is taken from the June 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Nearly three centuries after excavations at Pompeii first started, there is still an enormous amount of buried Roman treasure to uncover. Only a few months ago, Gabriel Zuchtriegel, director of the Archaeological Park of Pompeii, announced the discovery an unknown Roman villa.

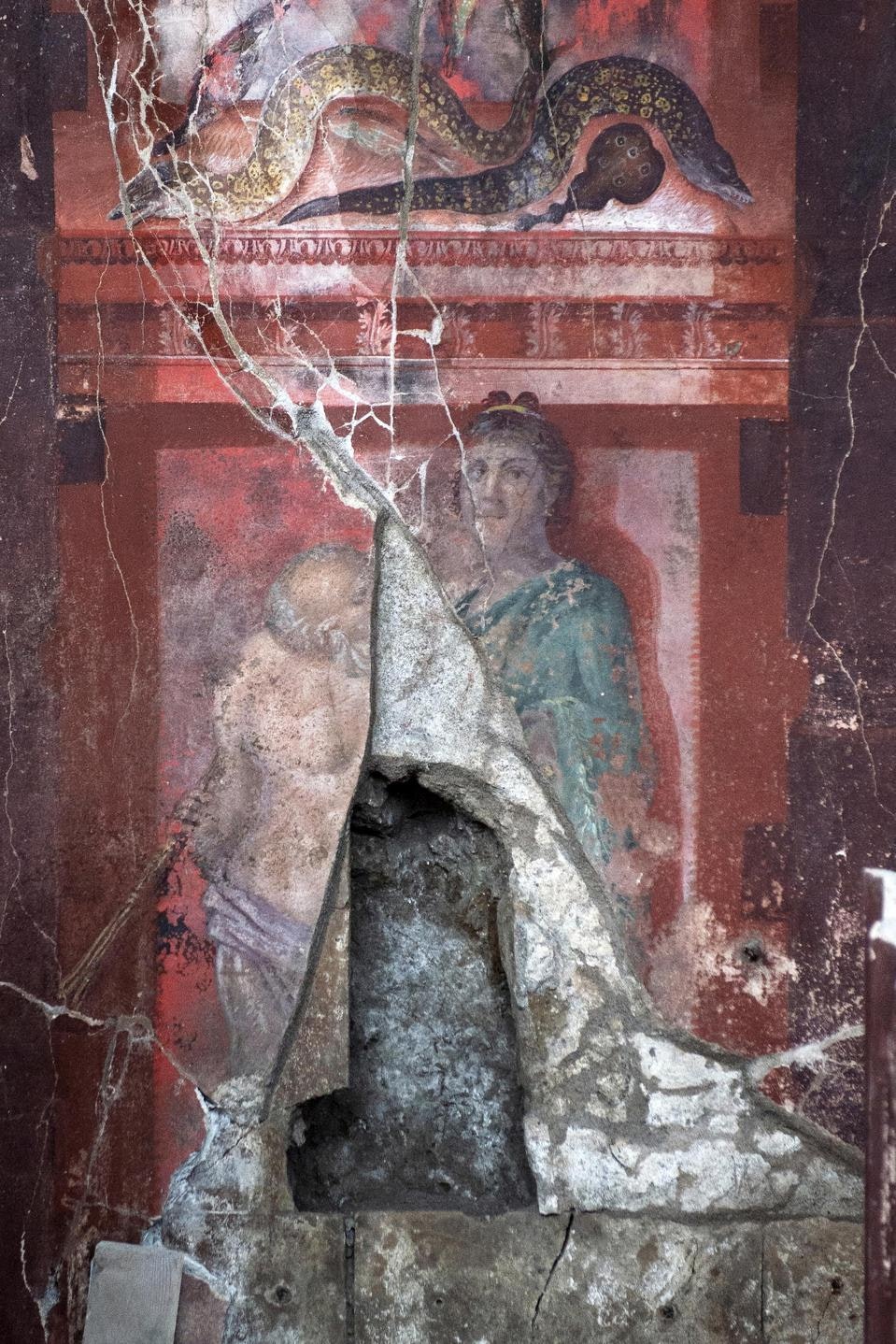

The most astonishing aspect of the House of Thiasus is the array of frescoes on the three walls of its colonnaded courtyard. The survival of any form of painting from the ancient world is rare, but wall painting has suffered particularly badly.

Wall paintings were very common in Antiquity. Everyone who could afford it adorned their houses with frescoes, and the grander the house, the more fresco decoration it had. Many public and government buildings had vast expanses of wall paintings. Very little of it has survived. Early Christians regarded most Roman paintings as obscene (they had a point: quite a lot of them are), sacrilegious and corrupting. Once Christians got political power, they set about destroying pagan painting wherever they found it.

Those wall paintings that survived were removed by two forces that are even more fatal to frescoes than religious fanaticism: water and sunlight. Exposure to sunlight bleaches out the colours and eventually fades a fresco to nothing. Damp detaches the layer of plaster with the painting on it from the wall. When wall painting from the ancient world has survived, it has done so because it has been protected from light and water.

The fiercely hot detritus that spewed from Vesuvius on 24 August, 79 AD destroyed some of Pompeii’s buildings completely and with them any pictures they contained. But for those areas that were merely covered with hot ash, the effect of the eruption was to provide a protective cover that kept out water and sunlight. That is why such a large portion of the Roman painting that we have today comes from Pompeii and the Roman towns near it that were buried by the eruption.

The pictures recently discovered in the House of Thiasus cover about 15 meters in length. Judging by their style, they were painted between 40 and 30 BC. The almost life-size figures depict women, some of whom are naked and dancing vigorously. There are also various men playing musical instruments; birds, flowers and winged cupids; scenes of hunting; animals such as fawns, goats and boars and lots of fish.

What do the images mean? Why were they chosen? The paintings had been on the walls of the House of Thiasus for over 100 years by the time Vesuvius erupted. Why were they kept for so long? Their iconography is not obvious. The scholarly consensus seems to be they represent aspects of the cult of Bacchus.

Bacchus/Dionysus was the god of wine, of fertility, of madness and of ecstasy. The dancing women may be “Maenads”, initiates into the cult of Bacchus who became intoxicated and freed themselves from the constraints of civilised Roman behaviour. Instead of staying at home and looking after their children and husbands, they went into the woods and danced wildly, eating raw meat taken from animals they tore apart with their bare hands.

In return, initiates were promised an eternal life of more or less continuous sensual pleasure. But we can’t be sure because no written sacred texts describing the essential beliefs of the cult of Dionysus have survived. There probably weren’t any such texts even in antiquity. The rites of the cult were meant to be kept secret and to be passed only from one initiate to another.

But even the pagan cults that were not obsessed with secrecy do not seem to have been interested in enforcing orthodoxy. They did not even set much store by belief in specific doctrines. Beyond the most generalised principles, they don’t seem to have cared about the details of an adherent’s beliefs at all.

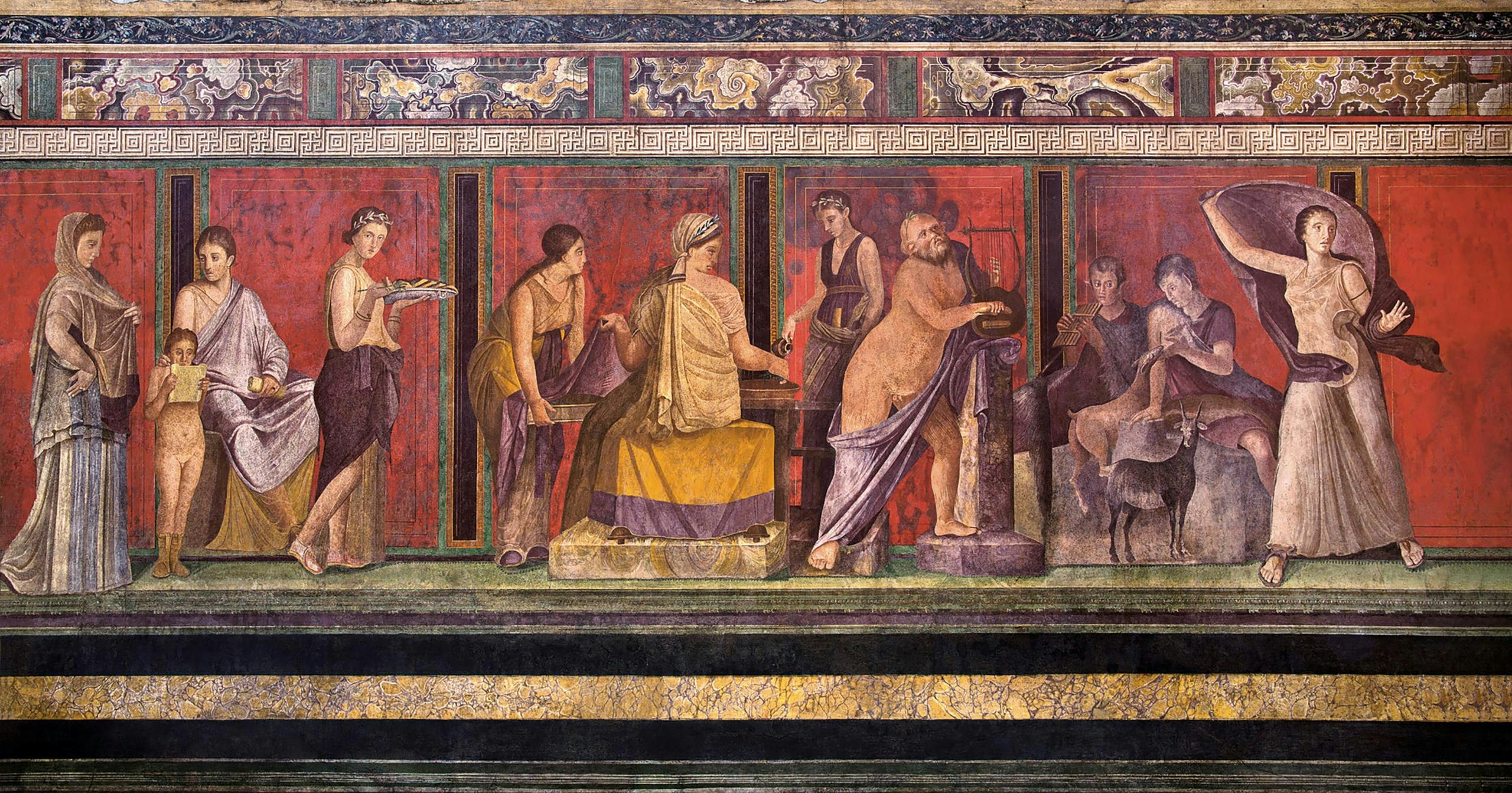

The absence of written sources means that our primary source for the interpretation of the pictures of Dionysiac cults in Roman Italy is … other pictures of Dionysiac cults in Roman Italy. Pompeii has another house which boasts frescoes dating from between 40 and 30 BC, which are also thought to depict Dionysiac rites. The frescoes in The Villa of the Mysteries also show women dancing, old men in contemplative poses, people playing musical instruments and animals — but interestingly, no fish.

Those frescoes have images that the frescoes in the House of Thisaus do not, such as a woman who appears to be being whipped and a picture of the god Dionysus himself. He is depicted as a young boy leaning on his mother’s lap.

The images that there are of Dionysus generally portray him as mild, gentle, fun-loving and harmless. These images are misleading. The legends that involve Dionysus show him as violently vindictive, torturing and killing those who either do not give him sufficient respect or do not recognise his divinity.

Euripides’ play The Bacchae, which was originally performed in Greece in 405 BC and which is a significant source of stories about Bacchus/Dionysus, has Dionysus driving the mother of the King of Thebes into a state of frenzy in which she tears her own son limb from limb after mistaking him for a lion. She does this with the help of several other women whom Dionysus has also conveniently caused to become frenzied. Her son “deserves” this dreadful punishment because he has killed some of the followers of Bacchus/Dionysus and denounced the god himself as a fraud.

The Bacchae also describes one of the many versions of Dionysus’ birth, death and resurrection: how he was fathered on the mortal Semele by Zeus, the immortal chief of the Gods; how Zeus accidentally killed Semele when she was pregnant with Dionysus and how Zeus then implanted the foetus of Dionysus in his (Zeus’) thigh, thus ensuring that Dionysus was eventually born undamaged, having grown into a baby nurtured by his divine father’s body.

Even by the high standards of absurdity characteristic of many Greek myths, this story is incredible. The initiates into the cult of Bacchus/Dionysus probably did not take it literally: by the time the pictures of Bacchic cults were painted in Pompeii, belief in the literal truth of the myths that made up the huge variety of pagan polytheism seems to have been fading in Rome.

Educated opinion was probably more accurately reflected by philosophical works such as Lucretius’ poem, On the Nature of Things, which states that, if the gods exist, they take no interest in humanity. There is no life after death, so no reason to be frightened of dying.

Edward Gibbon, in his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, maintained that, by the time of Augustus’ accession as emperor in 27 BC, the doctrine of immortality was “rejected with contempt by every man of liberal education and understanding”. He also claimed the decline of the belief in immortality left many Romans with a spiritual void that would eventually be filled by Christianity.

Gibbon didn’t see Bacchic cults as another way of filling that void, but some later historians have done so, stressing that one way the Bacchus stories were interpreted was as a kind of metaphor for eternal life. The rituals of drunkenness, “divine madness” and ecstatic sex were interpreted as activities that would eventually make eternal life a reality for the initiate.

Of course, it is also possible that followers of Bacchus/Dionysus didn’t interpret the Bacchic myths in that way — or in any way at all. Instead they used them as an excuse for having a party, getting drunk and indulging in orgies of various kinds.

That is more or less what the Roman Senate’s inquiry into Bacchic practices seems to have concluded in 186 BC. Two sources of that inquiry exist today. One is Livy’s History, written between 29 BC and 7 BC. The other is a bronze tablet dating from 186 BC that records “the Senatorial decree concerning the Bacchanalia”. That decree prohibits any form of celebration of Bacchic cults, except for those which had the explicit permission, in advance, from the Senate. Anyone found guilty of disobeying the decree will be executed.

Livy says that what precipitated the ferocious senatorial decree was the discovery that the worship of Bacchus was happening on a wide scale and that what took place most of the time wasn’t really worship at all: it was straightforward criminality — not just intoxication and wild sex but also the forging of documents such as wills and bloody violence including murder. The Senate saw this as a very serious threat to the stability and order of Roman rule in Italy. Hence its decision to suppress the cult.

The Senate’s persecution didn’t work. Despite rigorous enforcement of the law and — according to Livy — thousands of executions, the worship of Bacchus/Dionysus continued. So did the rituals involving drunkenness and “ecstasy” of various kinds.

Over the next century, the stigma attached to Bacchus worship seems to have died down in the Roman world. By the time Mark Antony entered the city of Ephesus with Cleopatra in 41 BC, he was able to do so dressed as Bacchus. The city’s population came out to meet him dressed as celebrants of the Bacchus cult. Ephesus had been in the Roman province of Asia Minor for nearly 100 years. It was thoroughly Romanised.

Clearly, neither the city’s administrators nor its people had any problems with Bacchic cults. And nor did Octavian. The future emperor Augustus never tried to persecute the followers of Bacchus.

Antony dressed himself as Bacchus at about the same time that the frescoes in the Villa of the Mysteries and the House of Thiasus were painted in Pompeii. The fact that those frescoes were painted at all is itself evidence of the cult’s acceptability. They were not secret or hidden: neighbours would have known what was being painted. Probably half the town did. There is no evidence that the authorities were in the least bothered. Perhaps by then orgies were socially acceptable. Or perhaps Bacchic rites, whatever they were, were no longer seen as threatening to Roman order.

Bacchic cults would continue to be a presence in Roman life for several centuries, especially in the provinces of the empire bordering on the Mediterranean. Bacchus/Dionysus is one of the most frequently represented characters in Roman art of the Imperial period. Mosaics have survived far more often than frescoes. The many magnificent mosaics depicting Bacchic myths are a testament to the cult’s popularity with the rich and powerful.

The cult survived the coming of Christianity. As late as 692 AD, a major church council in Constantinople was anxiously exhorting Christians to beware of the worship of Bacchus and not to participate in any of festivals associated with him.

Pompeii keeps turning up extraordinary things, but we are ignorant of a great deal about the civilisation that produced them. The meaning of the beautiful frescoes in the House of Thiasus remains a mystery. We don’t know why they were commissioned or what they meant to the Romans who woke up, got dressed and looked at them every day. We don’t know whether they had a deep religious significance for those people or whether they were merely amusing and artistically pleasing.

But then that is how the adherents of the Bacchic cults wanted it to be. They hoped their beliefs would be mysterious to outsiders. 2,000 years later, they still are.