This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Can the licence fee survive? The BBC Charter review is underway. It started under the last government (I was part of an advisory panel on funding), paused for the election, then landed in the lap of Lisa Nandy.

There is a chicken-and-egg tension about these reviews. Which should be decided first: the BBC’s purpose or the means of financing it? Typically, the issues are resolved separately, but in parallel, not least because the only financing option under consideration has been the licence fee.

The last review, under John Whittingdale, provided the option of subscription as a supplement to the licence fee, but the BBC has simply ignored that. So the political decision was reduced to setting the cost of the TV licence almost irrespective of the BBC’s purported purpose, along with the duration of the fee agreement and the arrangements for adjusting its level (historically, only ever upwards) during that period.

✺

Since the 2016 review, much has changed. Most notably, the value of the licence fee has been sharply eroded by a combination of price freezes and inflation, to the tune of a 30 per cent real-terms decline. The BBC has adjusted to this straitening of its finances by steadily reducing its quality of output (though it stoutly rejects any such accusation, and would point to its healthy collection of awards at the recent BAFTAs).

But the truth is that, however slow the process of dilution, it is continuous. The BBC can these days rarely, if ever, venture into production of the most expensive high-end dramas, especially as an hour of it now costs £2 million: enough to fund, for example, a whole season of 50 hours of Pointless (a series which is readily repeatable).

Moreover, the BBC remains massively overstaffed, with 17,000 employees. Last year, the BBC spent £84m on restructuring, but reduced its headcount by just 22. Its claims to be especially efficient are risible: the figure of 5 per cent of its income that the BBC claims is spent on overheads has been exposed as more like 45 per cent. And it remains bitterly opposed to any idea of replacing the licence fee with a subscription system.

Much of this opposition is expressed as a defence of universality, a so-called principle which has very little basis in the BBC’s history, where for long periods entire services were only physically available to a minority of households. That subscription services are in practice universally available — but with no compulsion to pay for them, unlike the licence fee — is a fact that seems to have escaped the ideologues of Broadcasting House.

The BBC has no qualms about the compulsory element of the licence fee system. However, even though the number of prosecutions for non-payment has dropped from a pre-Covid annual peak of over 150,000 to around 30,000 currently, the demonstrable unfairness of the way the law is enforced is a source of embarrassment. Overwhelmingly, those who are caught out by the TV Licensing officers are single mothers, the unemployed and the disabled — those most likely to be at home when the doorbell is rung.

The Single Justice Procedure, under which licence non-payment penalties are these days enforced, has made matters worse. Vulnerable groups are those least likely to be able to respond to a court notice within the 21 days allowed, or to know how to plead mitigation, let alone ensure the magistrate presiding over their case ever sees any plea of mitigation.

Lisa Nandy is not the only culture minister to have flirted with the idea of decriminalising licence fee evasion: a measure the BBC estimates would cost it hundreds of millions each year.

The other unfairness, which does cause the BBC some discomfort — even though it has been integral to the system for 100 years — is that, with a flat rate, the poor pay the same as the rich. The BBC has strongly hinted, on more than one occasion, that a different and more progressive collection mechanism would be preferable: most obviously, by adding the TV licence fee to council tax bills. Superficially, one can see the attraction.

The banding system makes council tax relatively progressive, even if the compression of the bands means that increases in house values only affect the lower bands — band H covers everything from about £1 million in value to £20 million or more. In effect, the £3.7 billion generated annually by the licence fee would mean adding a surcharge of 8 per cent to council tax bills.

Given that far more people are in council tax arrears — 1.8 million, with arrears of over £6.6 billion — than fail to pay the licence fee, the BBC might easily lose not just control over its overall finances, but any reliability of cash flow. Indeed, the imposition of a surcharge would inevitably make collecting council tax even harder, increase arrears and no doubt incentivise councils collectively to resist such a move.

Some councils — in the Midlands or the North-East, for instance, where the BBC spends little of its billions — might even ask why they should shoulder the burden of collecting money to pay high salaries to hundreds of BBC executives living in Camden, Dulwich or Barnes. Scotland, for instance, might choose to challenge the BBC’s editorial as well as financial policies.

Beyond that, the modestly progressive structure of council tax could lead to the replacement of perceived unfairness by organised resistance. A typical band H home would be paying £250 for what previously cost £174.50. For the one million people who own second homes, £174.50 would be become £500. For those of them now being charged a 100 per cent second home premium, the total would be £750.

Two possible consequences flow from such calculations. First, a substantial constituency could well be created of people who believed the cost of paying for the BBC was far too high. Such a grouping might join — or lead — a campaign to force the BBC to operate on the basis of voluntary subscription (Netflix, reasonably, charge just one subscription, however many homes you might have, as you can only watch their service on one screen at a time).

For the BBC not to have contingency plans for a swift abolition of

the licence fee would be a gross dereliction of duty

Secondly, many might join the exodus from live television altogether, thereby obviating the requirement to have a television licence, and so presumably exempting them from paying the council tax surcharge. And as councils would not benefit in the slightest from the surcharge, they would have little interest in checking whether live television was being watched. It is conceivable that the BBC at that point would simply lobby ministers to make the payment a BBC tax, not connected to any device or screen or behaviour, payable irrespective of whether you owned a TV or radio or watched or listened to any live broadcast.

Such a draconian outcome is unlikely to be electorally popular, and even a Labour government might baulk at the prospect. Rather more importantly, a potential Reform UK government — already committed to abolishing the licence fee as it stands — is sure to oppose any such iron-cladding of the BBC’s finances. Indeed, for the BBC not to have contingency plans for a potentially swift abolition of the licence fee after the next election in the event of a Reform UK victory would be a gross dereliction of duty.

The looming threat of Reform UK is sharply visible. Less obvious is the rapid shift in viewing habits and household technology which may undermine the licence fee from within.

Ten years ago, much of the resistance to replacing the licence fee with subscription was based on the fact that millions of people were out of reach of broadband. Today, fast broadband is available to 99.7 per cent of households, and more than 70 per cent have connected it to their television sets. In excess of 18 million homes subscribe to the likes of Netflix and Sky. Another 14 per cent of households have broadband, but have not yet connected it to their TV.

The remaining 14 per cent of households are within reach of broadband but have yet to take advantage of its availability, most likely on account of unfamiliarity with matters digital, or lack of interest, or cost — though suppliers such as BT offer social rates below £20 a month. Typically, these households comprise adults who are alone, and older and poorer than the average: 90 per cent are over the age of 55, and 80 per cent are in the C2DE demographic.

✺

In parallel with the spread of streaming services and smart TVs (nearly all new sets can connect directly to streaming, bypassing the traditional transmission system) there has been a steady shift of viewing away from live TV to on-demand. Today around 50 per cent of all TV viewing is still linear, but official forecasts say it will drop to 30 per cent within five years, and then continue the downward trend. Most viewers combine differing proportions of both linear and on-demand content (these homes are called hybrids), but over five million homes are already completely non-linear: that is, entirely dependent on streamed content.

A further one million homes each year are opting out of live TV, thereby eliminating the need to own a TV licence. Use of the BBC’s streaming service, the iPlayer, continues to require ownership of a licence, and the BBC makes registration a condition of using this free-to-air content so it can pursue non-payers: but there have been no recorded cases of any non-paying users being prosecuted. So the BBC now stands at the edge of a steep precipice.

In recent years, half a million homes have cancelled their TV licence. The BBC believes the rate of exit is no more than 1 per cent of eligible households a year, which is below the level by which the cost of the licence fee — and thereby the BBC’s income — rises each year as long as it remains inflation-proofed. That trade-off, it thinks, would be survivable, if uncomfortable. In fact, the rate at which the number of TV licences is falling accelerated from 300,000 in 2024 to 360,000 in 2025. Only another 3 per cent boost to the cost of the licence fee (on top of the previous year’s 6.6 per cent) has kept the BBC’s income steady.

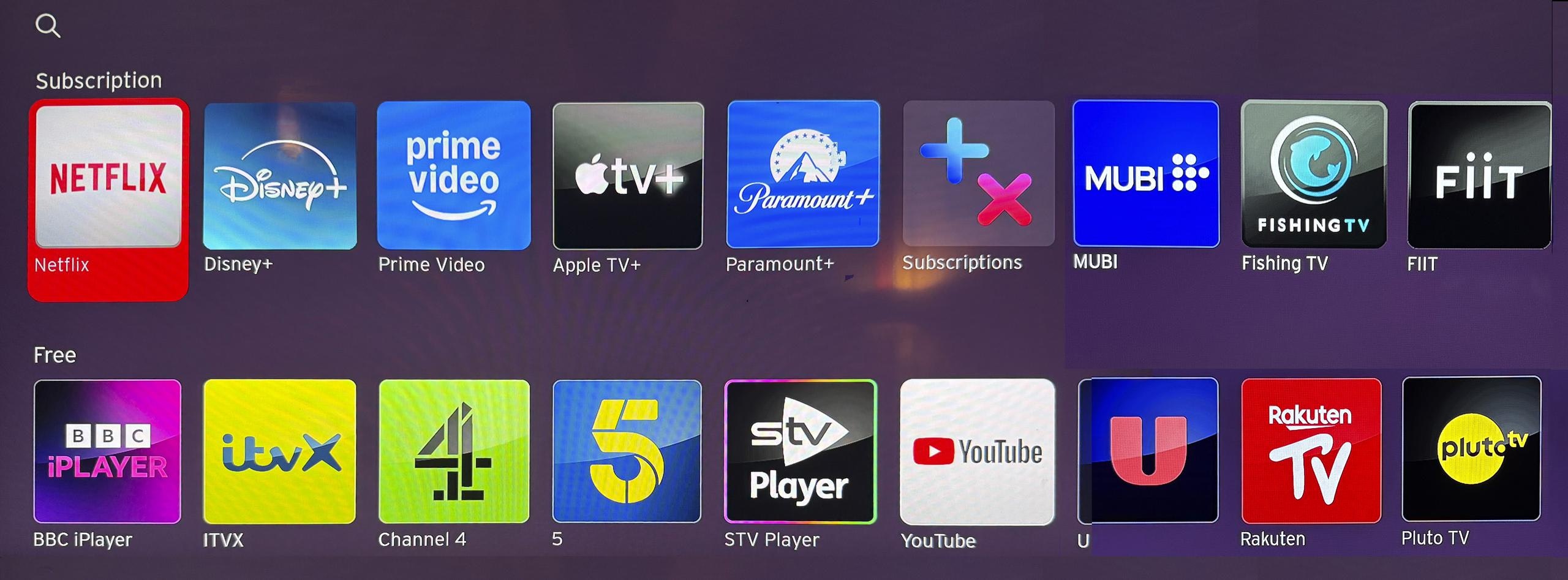

But as more streaming services are launched, alongside dozens of existing ones, including those from Netflix, Disney+, Apple TV+, Paramount and the extensive free-to-air offerings from ITV, Channel 4 and Five, viewers will inevitably wonder why they should continue to spend £174.50 a year, or wherever index-linking takes it, in order to watch the diminishing proportion of all content that is consumed live — especially as news is constantly available online, not least from the BBC itself.

The modelling on TV licence cancellation I have seen assumes the process will slow to a halt by 2026 at perhaps 14 per cent of all households, or — downside scenario — 18 per cent: all this within a context of a steadily rising number of households, caused primarily by immigration. But I know of no reason why there would be a halt in the process. The viewing audience is not a solid block. Like a glacier, whole chunks can break off very rapidly.

Currently, in a typical week, a majority of 16–24s watch no live television at all. Neither the 14 per cent nor the 18 per cent seems carved in stone as fixed end points. Based on current consumer behaviour, the figure for households abandoning the licence fee seems likely to continue rising, and even to accelerate. Were it to reach 20 per cent, let alone 30 per cent, the pressure to abandon the licence fee system would become irresistible.

Speaking recently to an industry forum, a former senior BSkyB executive, Mike Darcey, described the licence fee as a voluntary subscription even now. With prosecutions in the tens of thousands and non-payment in the many millions, the likelihood of any non-payer being successfully prosecuted is currently very low.

✺

There is one more joker in the pack: the fate of the digital terrestrial transmission (DTT) system. For years, the continued reliance by millions of households on DTT signals, typically received through a rooftop aerial, has been cited as a reason why the BBC could not switch to subscription, which requires an internet-based payment system.

As it happens, the argument is misleading and mistaken, in that proponents of subscription assume that one or more DTT-delivered free-to-air public service channels would be retained (funded by the Treasury rather than the licence fee), and dove-tailed with a portfolio of BBC subscription services.

But within a handful of years, the world body that allocates broadcasting frequencies is due to decide DTT’s fate. There are good arguments for releasing that spectrum for other uses. Moreover, the UK’s terrestrial channels — including, remarkably, the BBC — have been speculating publicly about the relative cost (hundreds of millions of pounds a year) of maintaining DTT transmissions, when more and more investment is being poured into streaming.

Twenty years ago, there was an expensive transition from analogue terrestrial broadcasting to DTT, in order to make more efficient use of available spectrum. Whether or not the DTT system survives is not strictly relevant to the case for replacing the licence fee with subscription: but if DTT is indeed abandoned, a voluntary subscription mechanism will be the only available option for funding most of what the BBC does (assuming the Treasury covers the cost of certain types of public service output that subscription would not support).

Given the inexorable trends in consumer behaviour, content provision and technology, and the looming shadow of Nigel Farage, the BBC’s room for manoeuvre appears very limited. In the short term, decisions lie with Lisa Nandy, but an organisation as large and important as the BBC should surely not be substantially dependent for its future financing on what one of its most illustrious presenters once called a here-today-and-gone-tomorrow politician.