There probably isn’t anyone else alive who can remember what was showing on ITV 50 years ago today, just after 8.15pm. I can.

It was And Mother Makes Five, starring Wendy Craig as a dizzy, harassed housewife in what would now be called a blended family.

I was 14 and watching it with my own mother in our living room, what we then called the lounge. There’s a lot of ‘then’ and ‘now’ in this story.

We lived in a small, semi-detached, between-the-wars house backing on to a railway line in Southport, the genteel seaside town that in the summer of 2024 acquired unwanted global fame when three little girls were stabbed to death in a dance class there.

The youngest of them, Bebe, was the beloved granddaughter of one of my oldest and dearest friends. I feel very connected to that tragedy.

But if there’s a death that has shaped my life it was the one I was about to learn of on February 4, 1976 (a Wednesday then as now), halfway through And Mother Makes Five.

If there’s a death that has shaped my life it was the one I was about to learn of on February 4, 1976 (a Wednesday then as now), halfway through And Mother Makes Five, writes Brian Viner

Our family was just my mum, my dad and me. My father, Allen, was mostly in women’s underwear. Which is to say, he ran his own business in nearby Liverpool, buying ends-of-lines from manufacturers and selling them on to department stores and market traders.

He dealt mainly in bras and knickers, though occasionally he would trust his instincts and branch out, all too often finding that his instincts had let him down. He once bought 10,000 multi-coloured rubber grips for removing tight lids from jars but, as I recall, only sold about three of them.

The upside was that in our house we were never confronted with a jar lid we couldn’t get off. With enough manpower, we could have removed thousands of them at the same time.

My mum, Miriam, worked in the company, too, alternating between secretarial duties and boxing up bras in a rented Victorian warehouse near the Liverpool docks.

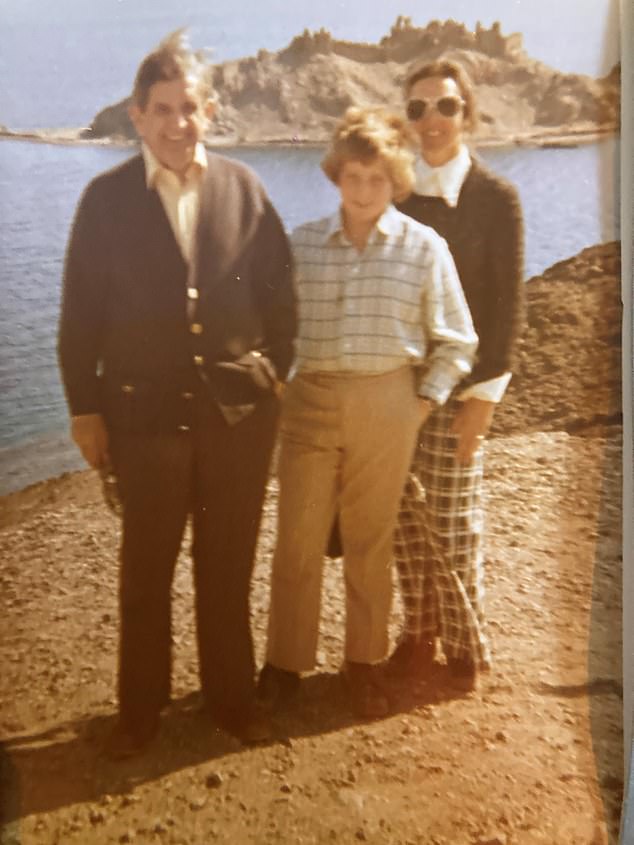

It wasn’t a lucrative enterprise and my dad’s lifelong gambling habit didn’t help, but we were comfortable enough, with a fortnight in Spain or Portugal when bras and knickers were doing well enough to insulate the holiday package deal from the horse-racing and poker losses.

Dad always liked to have a decent car, too. He thought it was good for business. Our family car in 1976 was a bronze Ford Granada, like the one in The Sweeney.

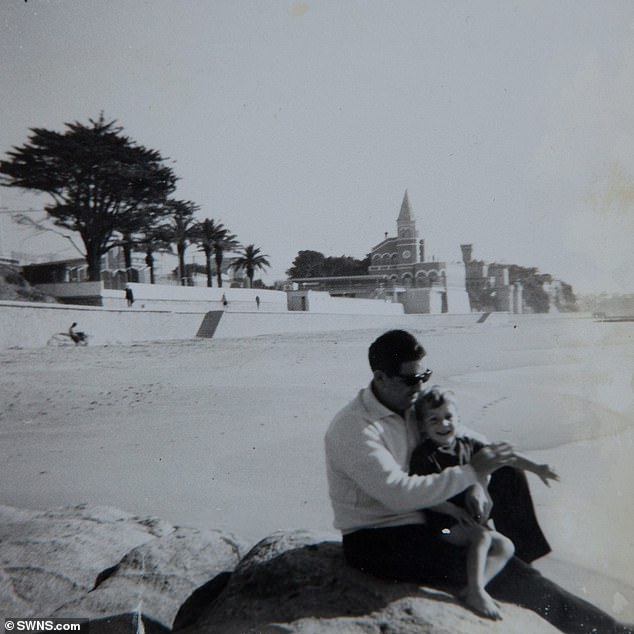

He was a good father, loving and engaged, funny, and a wonderful raconteur with proper stories to tell: he’d been an RAF flying instructor during the war.

He was also my faithful ally in regular spats with my mum. She was lovely too, elegant and cultured, but she could be formidably fierce.

My dad was 60, much older than the fathers of most of my friends, but then he’d been 46 when he and my mother adopted me, as a three-week-old baby.

Miriam and Allen Viner adopted Brian when he was three weeks old. Brian never tried to found out more about his birth parents as it would have felt ‘wrong, unsettling, disloyal’

Allen and Brian on holiday in Portugal around 1965. He was a good father, loving and engaged, funny, and a wonderful raconteur, says Brian

I’d known since the age of ten that I was adopted but even as an adult I never wanted to find out more about my birth parents.

It would have felt wrong, unsettling, disloyal. I knew nothing about them until I was 37, when, after a decade of looking for me, my biological mother made contact. That’s another tale.

My dad wasn’t home when the doorbell rang just after 8.15pm that Wednesday evening 50 years ago. He’d set off for London in the afternoon, taking the train from Liverpool Lime Street on a trip to see one of his main suppliers, a man called Roy Dickens who worked for Triumph International.

I went to answer the door and through the frosted glass saw two people in uniform. The Salvation Army, at this time of night?

It turned out to be two police constables, a young woman and an older man. I showed them into the lounge and my mum, duly alarmed, switched off Wendy Craig.

The male officer told us that my dad had suffered a massive heart attack on the train and was thought to have died almost instantly. I still remember my mother’s wail, a sound I’d never heard before. In her anguish, she had to go to Liverpool to identify the body. I stayed behind.

I was off school for nearly three weeks, more than happy to miss double-maths but readjusting to a dismal new equation at home: And mother made two.

When I did go back, I was treated with a kind of extravagant nonchalance, as if nothing had happened. It was an old-fashioned boys’ grammar school, surnames only, and our form master had instructed the class not to mention Viner’s father.

But my pal Venables, just in front of me in the register, decided after consultation with his own father that this was wrong. In one of the long parquet corridors, he drew me aside and said how sorry he was, cementing a close friendship that thrives to this day. We’re on first-name terms now.

There is no good age for a boy to lose his dad, but 14 might be about the worst. Compounding the abrupt departure of the only male role model I’d ever had, puberty soon struck like a hurricane and blew my moorings, already dislodged, clean away.

Caught in a testosterone storm, I stopped working towards my O-Levels and started using what I liked to think was my wit to bait other boys until only fists could settle matters.

If I can apply modern psycho-babble to events of half a century ago, I think what I was suffering from was loss of status.

I don’t really mean material status, although our foreign holidays stopped and the stylish Granada was replaced by a functional Escort (once my mother had hurriedly learnt to drive). I mean familial status. All my friends had fathers. Most of them also had siblings.

I’d never minded being an only child before, but the absence of both suddenly felt like an embarrassment, a stigma.

I vividly recall a classmate announcing that, to the great surprise of him, his dad, his brothers and sister, his mum was expecting another baby. Everyone else seemed happy for him. I felt sick. It was further evidence that life had somehow cheated me.

I couldn’t share any of this with my mum.

In fact, I stopped communicating with her very much at all, except when we had screaming rows because she wouldn’t let me go to some party or other.

I’m still relieved that, at the height of those tumultuous ding-dongs, I never yelled ‘You’re not even my real mother!’ It was the nuclear option, yet it never remotely occurred to me. She was my real mother.

The Viners in Greece around 1974. Two years later Allen would have a fatal heart attack on a train to London

Nevertheless, I feel a stab of remorse when I think back, because, as well as dealing with her own grief while keeping the business going, working all hours, she also had me to worry about, a bright boy seemingly about to flunk his exams and unwilling to talk about anything much, least of all his feelings.

These days there would be counselling. In those days, there was only rebellion.

I skived school (nobody called it truanting back then) and flirted with shoplifting.

But 1976 was a formative year in good ways as well as bad. Little though I understood it at the time, my father’s death and the emptiness that followed made me cherish and protect relationships not just then but long into adulthood.

Male friendships especially became crucially important to me and they still are… I work hard to keep them ticking over and stay in regular contact with maybe 50 old friends from school and college days (miraculously, I scraped six passes in my O-Levels and later mustered good enough A-Levels to get to St Andrews University).

Of course, that may well have been the case even if my father had lived into his 90s, but I have no doubt that losing him when I did, before I could bond with him on a man-to-man basis, share a beer or a grown-up joke with him, explains why I have always so valued male company.

Quite often, when I go to a football match or play golf or snooker with my two grown-up sons, I feel as if I’m doing it for my dad.

I have a daughter, too, a beautiful young woman who is getting married soon.

It was almost a visceral urge for me to have a big family of my own. But it pains me that my children never knew their paternal grandfather’s warmth and that he never knew their radiance.

Privately, I keep him alive in my head, more often than you’d think after 50 years.

Sometimes, when my wife Jane and I are watching TV, I steal a sidelong glance at her to see if she’s smiling, aware that as a kid I did the same with my dad. Sometimes, I watched him more than I watched the telly.

Most of my memories of him now are blurred, just as the only photos I have of the two of us together are slightly out of focus. But I do carry one mental image of him that remains sharp and undimmed. It dates from the autumn of 1975, and it’s him sitting forward in his Parker Knoll armchair crying with laughter at the first series of Fawlty Towers.

About 25 years ago I interviewed John Cleese. We met for lunch in a Greek taverna in north London and once we’d ordered I wondered whether to thank him for his central role in that golden memory of my dad.

Might it seem mawkish, or manipulative? But I did and to my horror Cleese’s eyes filled with tears.

He stood and reached across the table towards me, whether for a handshake or a hug I wasn’t sure, but we ended up doing a sort of awkward high-five and this very peculiar spectacle of two Englishmen emoting ended with him bumping his head on the ceiling and me getting a blob of taramasalata on the elbow of my jacket.

Around the same time, Jane and I started going with our children to Cornwall every August.

For ten years, we stayed for the same ten days in the same two rooms of a traditional seaside hotel, gradually befriending the other families who went at the same time. Although, again, there was a decidedly English reserve at play: a few years passed before we had a drink together, and another couple before we went to the beach, and two or three more before we all went out for dinner. You mustn’t rush these things.

One of the families we liked very much: a mother, father and their son, an only child. Eventually, thinking it would be nice to see them away from our August holiday, we invited them to our house for the weekend.

After Sunday lunch, while all the children played in the garden, the mum, Angela, a delightful woman of about my age, suddenly said: ‘Brian, do you mind if I ask you something personal?’

‘No, go ahead.’

‘Is your father still alive?’

‘Gosh, no, he died a long time ago, when I was 14.’

‘Right.’ Angela paused. ‘Did he die on a train?’

It was a startling moment. How on earth could Angela know?

‘Because,’ she said gently, after I’d stammered the question, ‘he was going to London to meet my dad, who was at Euston, waiting for him. His name is Roy Dickens. He worked for Triumph International. The day Allen Viner died was a big deal in our house.’

I still tell that story sometimes, not just because it so wonderfully exemplifies British reticence – it probably took Angela eight years to put two and two firmly together – but also because it shows how utterly extraordinary the twists and turns of life can be.

I wish my dad had enjoyed more of them, and that he had at least lived to see the second series of Fawlty Towers.