It’s a tough time to be a Democrat.

The party is locked out of power in Washington, largely relegated to the sidelines as President Donald Trump pursues his sweeping agenda. Republicans are trying to redraw congressional maps in Texas and other states, adding potential hurdles to Democrats’ efforts to take back the House in 2026.

Then there are the polls.

Why We Wrote This

Frustrated Democratic voters describe their party as “weak” and “tepid.” As Democrats try to regain their footing ahead of next year’s midterm elections, some are calling for fresh faces and fresh thinking.

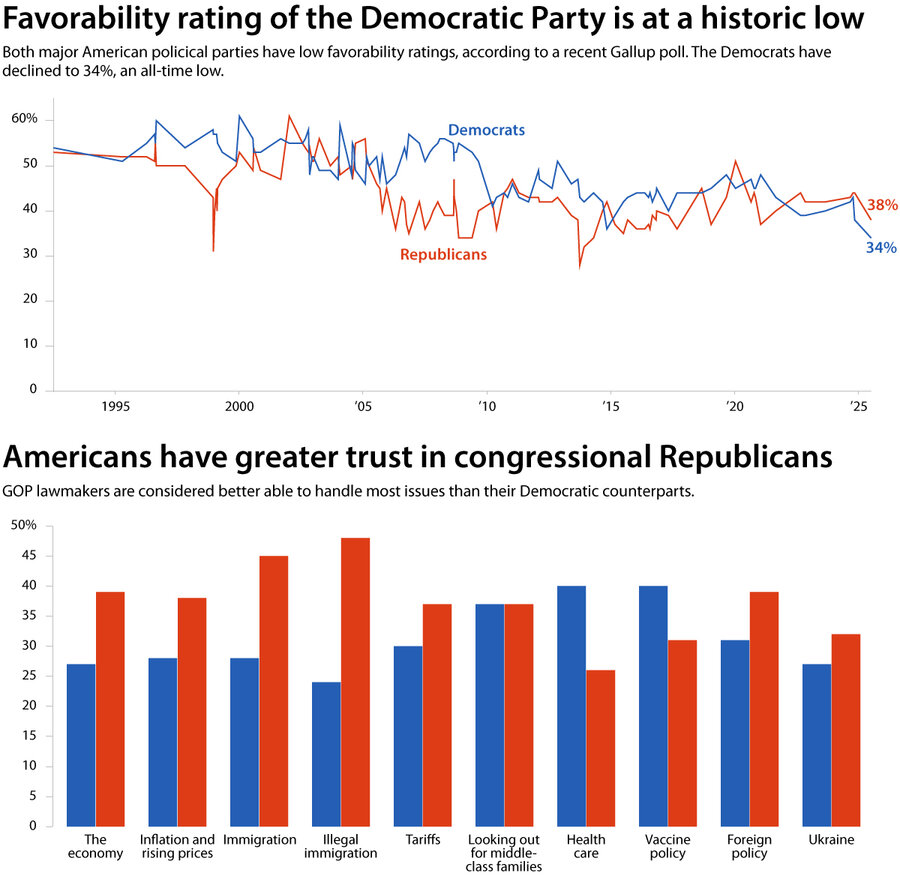

Despite the fact that Mr. Trump’s approval rating has fallen to its lowest point since Inauguration Day, Democrats are facing historically ugly numbers of their own. Poll after poll has shown them to be underwater, with higher unfavorable ratings than favorable ones. In four July surveys, Democrats were between 26 and 30 percentage points underwater, hitting levels of unpopularity not seen in decades. In the long-running Gallup survey, the Democratic Party’s approval rating hit 34%, the lowest ever recorded by the polling firm.

One subgroup driving the Democrats’ poor ratings: their own base. A recent CNN poll found that Democratic voters currently hold far more negative views of their own party than Republican voters do of theirs. At town hall events and in focus groups, frustrated Democrats say they want their representatives to push back harder against the Trump administration. But congressional Democrats have few tools to do so, especially as the courts have allowed Mr. Trump to keep expanding presidential power.

“Outside of banging your fist on a table, there aren’t many mechanisms on the federal side for Democrats to step up and stop the president,” says Rodell Mollineau, a Democratic strategist. “That’s what’s really driving this sense of despair and hopelessness coming from the base. They want Democrats to do something about it, but they can’t.”

Democratic politicians eyeing potential 2028 presidential runs have tried to break the despair cycle with marathon speeches, social media tit for tat, and stunts such as hosting Texas legislators who fled the state in their attempt to block Republican gerrymandering efforts.

But the party remains without a clear leader. Complicating the messaging challenge, its base has moved left since Mr. Trump’s first term, with more Democrats self-identifying as liberals, even as the party grapples with an urgent need to woo independent voters who helped Mr. Trump win all seven swing states last November.

Democratic operatives admit the base’s frustration is cause for concern, particularly if it depresses turnout. But some also see it as fuel for much-needed change. For Democrats to be successful in 2026 and 2028, they can’t keep doing things the same way, they say. And Democrats will have to start by showing they can respond to disgruntled voters – both far-left and moderate – who are increasingly unhappy with politics as usual.

“This is an opportunity,” says Jennifer Hilsbos, chair of the Pinal County Democrats in Arizona. “We like to talk and explain things, but we don’t spend enough time listening. No one was sitting down at kitchen tables last year and listening to voters say what they needed from us.”

Ms. Hilsbos, who was elected chair a few months after Mr. Trump took back Arizona on his romp to the White House last fall, has been spending three to five hours in a public place every week, so voters can come talk to her. She says she wants to show them her party can “focus on more than just the ‘isms,’” such as racism or feminism. In her increasingly red county outside Phoenix, that means more conversations about immigration.

“We have recognized there is a problem,” says Ms. Hilsbos, “and now we’re trying to address it.”

Young Democrats taking on incumbents

For many, fixing the party’s problems will require not just fresh thinking – but fresh faces. A slate of younger Democrats have already launched primary challenges against longtime congressional incumbents ahead of next year’s midterm elections.

Democrats’ rock-bottom polling “has been a long time coming,” says Harry Jarin, a Democrat running in Maryland against Rep. Steny Hoyer, a former House majority leader who has been in Congress for more than four decades. Voters have become disillusioned with the party, says Mr. Jarin, because veteran Democrats like Mr. Hoyer haven’t solved problems that matter to them, such as a lack of affordable housing. Worse, he adds, many voters don’t know what the party stands for.

“You could have gone to any polling booth in America on Election Day last year and the average voter [knew] what Donald Trump’s plan for the future was,” says Mr. Jarin. “I’m not sure you could have said the same about [Kamala] Harris or the Democratic Party.”

Mr. Jarin has seen that play out within his volunteer firefighting department. When he joined 12 years ago, the firehouse was split 50-50 between Republicans and Democrats. Now, he says, the entire department is “100 percent MAGA Republican” except for him and one woman.

George Hornedo has seen a similar drop in support for Democrats in Indianapolis, where 2024 voter turnout was the lowest in two decades. Mr. Hornedo, a Democratic strategist, has launched a primary challenge against Rep. André Carson, a nine-term congressman representing one of Indiana’s two Democratic House districts. He says Democrats need to rebuild their state parties.

“Too often, we bring spoons to a knife fight when Republicans bring a machete,” says Mr. Hornedo. “I may not like what the Republicans are doing, but we can’t say they aren’t thinking out of the box.”

When a recent Associated Press poll asked Democratic voters to describe their party, fewer than one-quarter offered positive adjectives. The most common descriptors were “weak” and “tepid.”

Frustrated – but still motivated to vote

Still, just because voters are frustrated with their party’s representatives doesn’t mean they’ll vote for the other side. In polls where Democratic voters have given their own party poor marks, they also have given Democrats an edge in voting preferences.

And, right now, Democrats appear more motivated to vote than Republicans. In the CNN poll from July, 74% of Democratic voters called themselves “extremely motivated” to vote in next year’s congressional elections, while only 54% of Republican voters said the same. If the election were held today, 46% of voters in a recent Wall Street Journal poll said they would vote for a Democratic candidate, compared with 43% who said they would vote for a Republican.

It’s not as clear an advantage at this point as it was in 2017, ahead of 2018’s “blue wave.” But Democrats have led Republicans in YouGov’s poll of a generic congressional ballot – where respondents are asked to pick between an unnamed Democrat and an unnamed Republican – for the past six months. And the Democratic Party surpassed the Republican Party in voter identification in the first half of 2025, according to Gallup, after the GOP had led through most of 2024.

“At the end of the day, elections are binary choices,” says DJ Koessler, a Democratic strategist who worked on Pete Buttigieg’s 2020 presidential campaign. Democratic voters might be frustrated with their own party, but their antipathy toward Mr. Trump’s GOP could be strong enough to make up for it.

Mr. Koessler expects Democrats’ poll numbers to improve as the midterm elections get closer and actual candidates are campaigning against Mr. Trump’s agenda – including his “Big Beautiful Bill,” which remains widely unpopular. To effectively convey their message, he and others add, Democrats will need to build a new media ecosystem through social media and podcasts, as Republicans have done.

“All this chaos is going to give us the opportunity to rebuild,” says Mr. Hornedo. “Do we rebuild back to what we have which wasn’t sufficient? Or do we have the imagination to think about what can be?”