The march toward electric cars in the United States took a U-turn in May when the Senate voted to revoke California’s electric vehicle mandate. And it’s not just about California. The move also applies to nearly a dozen states in step with the Golden State’s zero-emissions requirement, set to start phasing in next year.

President Trump has promised to sign the congressional action into law. And as soon as he does, California says, it will sue.

Regardless of the outcome, the revocation is a significant rebuke to states’ self-determination and, more specifically, any state hoping to push the nation to quickly abandon fossil fuels in favor of electrification for vehicles. The scientific consensus says greenhouse gas emissions must be cut dramatically within the next five years to mitigate the worst effects of climate change.

Why We Wrote This

The drive for electric vehicles, in California and beyond, is challenging carmakers to adapt faster than many deem possible or profitable. The Trump administration is pushing back by testing the limits of state governance.

“It will slow down adoption,” says Stephanie Valdez Streaty, of Cox Automotive Inc., a technology provider to the industry.

Here, the Monitor explains why California plays such an outsize role in auto emissions standards, why this has met strenuous pushback, and where things might go from here.

Why is California so important when it comes to auto emissions?

Because California’s smog is so bad, the federal government has, for more than 50 years, allowed the state to set its own emissions limits, resulting in more efficient vehicles and the nation’s most aggressive push toward electric vehicles. Other smoggy states have followed suit. But each new standard or rule requires approval from the Environmental Protection Agency, which has accepted all of the exceptions. Now Congress is saying “no,” not this time. Not for an EV mandate.

Back in the 1960s and 1970s, Los Angeles’ air was so polluted that some folks wore gas masks. Schools regularly sent kids home because of thick smog. You frequently couldn’t see the iconic Hollywood sign.

Vehicles were the main culprit, as was the area’s geography and climate. LA sits in a basin and gets lots of sunshine. When sunlight mixes with tailpipe emissions, it makes dangerous ozone. Smog in the basin has drastically improved, but as of 2020, more than 150 days exceeded the most recent federal ozone standards. Heavy truck traffic has also contributed to terrible pollution in California’s Central Valley. The EPA is considering fining Southern California for failing to meet federal air quality standards.

California’s influence is also due to its size. As the nation’s most populous state, it has the largest auto market. If California were a country, it would be the world’s fourth-largest economy. So when California sets new emission standards – and other states follow – the auto industry is compelled to adopt them.

As a result, the state has frequently exercised that power, driving changes in the nation’s standards and technology, including the adoption of catalytic converters. “California’s ambitious goals are what pushes the industry,” says Ann Carlson, who teaches law at the University of California, Los Angeles, and who helped write tailpipe emission policies for the Biden administration.

Why are Congress, the president, and the U.S. auto industry all pushing back on EVs?

Many people feel that California’s zero-emissions standard is moving toward an EV switchover too fast, and forcing that change on the nation. Climate change politics, too, play a role.

Beginning next year, the California mandate will call for 35% of the state’s new vehicle sales to be zero-emission or plug-in hybrid. That proportion is scheduled to rise to 100% by 2035. Other state rules that relate to medium- and heavy-duty truck sales and engine standards were also revoked by Congress and await the president’s signature.

“Democrats have this delusional dream of eliminating gas-powered vehicles in America,” Republican Sen. John Barrasso of Wyoming said on the Senate floor in May. “They want to force-feed electric vehicles to every man and woman who drives in this country.”

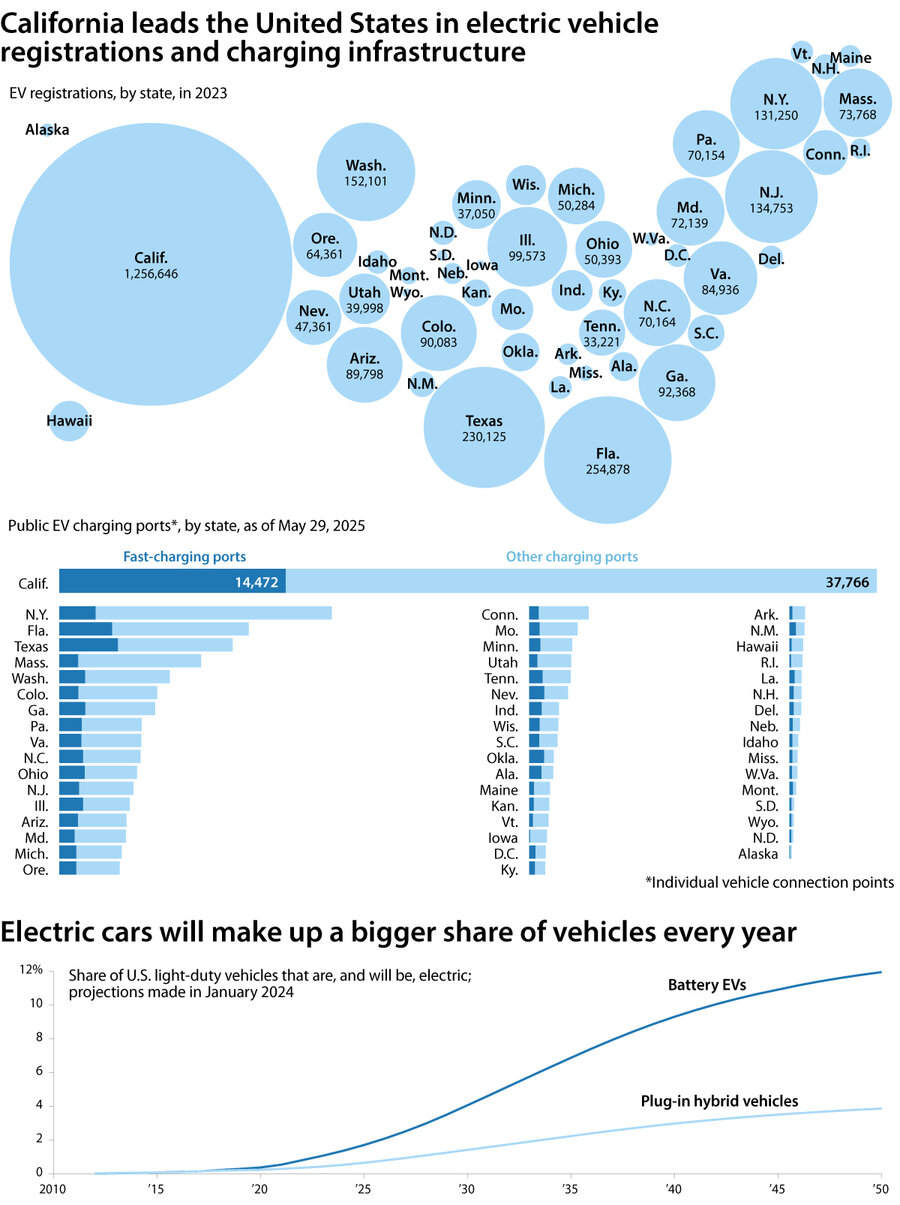

California leads the nation in zero-emission sales and EV infrastructure, with more than 1.25 million electric vehicle registrations and more than 52,000 public charging ports.

But California is behind in meeting its own mandate timetable – so far, EVs are 23% of all sales this year. And the congressional pushback was bipartisan in the House, where 35 Democrats supported the rollback of the mandate, including two from California. The Senate vote fell almost entirely along party lines.

Consumers have concerns about insufficient and unreliable charging stations, battery range and quality, and high prices for EVs. The sense among manufacturers and auto dealers is that “the market isn’t ready for these aggressive goals,” says Ms. Valdez Streaty. Automakers want guidelines for all states, not just some of them, she says.

What’s the outlook for EVs – and California’s role?

First, we’re heading into legal wrangling. Both the Senate parliamentarian and the independent U.S. Government Accountability Office said that the procedure used to block the California waivers was not allowed. That will be one thing California will argue when it sues to keep the mandate.

Republicans are also likely to cut federal infrastructure funds for charging stations and tax credits for purchasing electric vehicles. In April, EV sales took a hit after record sales in the first quarter, according to Cox Automotive. And then there’s the uncertainty around tariffs.

“It’s going to be a bumpy ride this year” for EVs, says Ms. Valdez Streaty, who expects more sales of gas and plug-in hybrids as transitional vehicles. At the same time, new all-electric models are being introduced, and battery range is improving, now averaging around 300 miles per charge.

“Long term, we’re still going to continue towards electrification, but the timeline to get there is going to shift and slow down,” says Ms. Valdez Streaty.

California’s political leaders say revoking the mandate will be expensive. According to the California Air Resources Board, which crafted the mandate, adhering to it would result in 1,287 fewer air-quality-related deaths, 1,110 fewer hospital and emergency visits, and $13 billion in public health benefits. It would also reduce greenhouse gas emissions by nearly 400 million metric tons – the equivalent of 100 coal-fired power plants’ annual output.

The nation, too, will pay a price in global competition, particularly with China, which is on a tear with lower-cost electric vehicles.

“We won’t stand by as Trump Republicans make America smoggy again — undoing work that goes back to the days of Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan — all while ceding our economic future to China,” said California’s Democratic governor, Gavin Newsom, in a statement.

It’s possible to see state authority restored, says Professor Carlson at UCLA. But California and other states “still have a lot of their own authority to try to stimulate electric vehicle demand and supply,” she says. They can build out charging infrastructure, provide tax incentives and subsidies, and favor electric vehicles in parking and carpool lanes. And they can work together, as they plan to in the recently announced 11-state Affordable Clean Cars Coalition.

Technology will continue to advance, with or without the California mandate, concludes Professor Carlson. The world, she adds, is moving in that direction.