In the gritty industrial town of Tangshan in northern China, Lin Liang pauses by the hulking mining company where he has worked in maintenance for 15 years. He has decades to go until he can retire with a pension – longer than he had planned, thanks to a recent mandate raising the retirement age across China.

Facing a rapidly aging population, which threatens to bankrupt the country’s pension system, Beijing last year started implementing its first increase in retirement age since the 1950s.

Younger workers such as Mr. Lin will be impacted most, with the retirement age for men gradually increasing from 60 to 63 over the next several years. The retirement age for women will rise from 50 to 55 for blue-collar workers, and 55 to 58 for white-collar workers. Though China’s statutory retirement ages are low by global standards, the change represents a hardship, especially for those who are engaged in physical labor or face greater job insecurity. Workers’ required contribution periods – or the amount of time the workers or their employer must pay into the pension system in order to reap the benefits – will also increase from 15 to 20 years between 2030 and 2039.

Why We Wrote This

To support its rapidly aging population and preserve its pension system, China is raising its retirement age for the first time in 70 years. At the same time, demand for broader pension reform is growing.

Contributions from Mr. Lin and others are currently supporting a ballooning cohort of elderly Chinese. About 22% of China’s population is over age 60, a figure projected to rise to 28% – or 402 million people – by 2040. The trend is driven by longer life expectancies and declining birth rates, exacerbated by China’s decades-long one-child policy that lasted until 2016.

“If the pension age is fixed and people are living longer, pensions are going to get more expensive and eventually the system is going to blow a gasket,” says Nicholas Barr, an economics professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science. A 2019 report by the state-run Chinese Academy of Social Sciences predicted that, without reforms, the main state fund that finances future pensions would be depleted by 2035.

“There has to be an increase in the state pension age,” says Dr. Barr, who advised China on pension reforms from 2005 to 2010. “But that leaves a lot of other problems unsolved,” including deep inequalities in China’s pension system, and hard economic trade-offs needed to sustain its funding.

Shaky job market

Wearing a vermillion Mandarin cap and traditional clothing, Mr. Qiao bangs a gong and welcomes visitors to Tangshan Banquet – a pavilion crowded with vendors cooking traditional snacks such as fried pastries, meat skewers, and sesame brittle.

Mr. Qiao, who asked that his first name be withheld for privacy reasons, worked for decades at a local chemical plant – grueling labor that included smokestack duty – before retiring early eight years ago.

But Mr. Qiao can’t complain about his pension, which is about 3,500 yuan a month, or about $500. And he supplements that with his earnings as a greeter at this popular food court in his hometown. He hardly considers this gig work, he says: “I want to [be here]. This job is fun.”

With his pension secured, Mr. Qiao is better off than many workers, both young and old, “concerned about whether they can even find a job on the labor market,” says Xian Huang, an associate professor of comparative politics at Rutgers University, who researches China’s social welfare system.

The unemployment rate among young Chinese has hovered close to 20% since the pandemic. Some in their 50s are also working overtime to support families and meet pension contribution requirements.

The decision to raise the retirement age sparked criticism online, where discussions on pension reform are full of “disagreement regarding … responsibility and cost sharing” between workers and corporations, says Dr. Huang. Some comments suggested the change is unrealistic, and penalizes young people. They also questioned whether private companies would employ older workers, noting how Chinese tech companies regularly lay off workers over the age of 35.

“Tell me,” asked one netizen, “what are we supposed to do for the remaining 30 years of our lives?”

Pension disparities

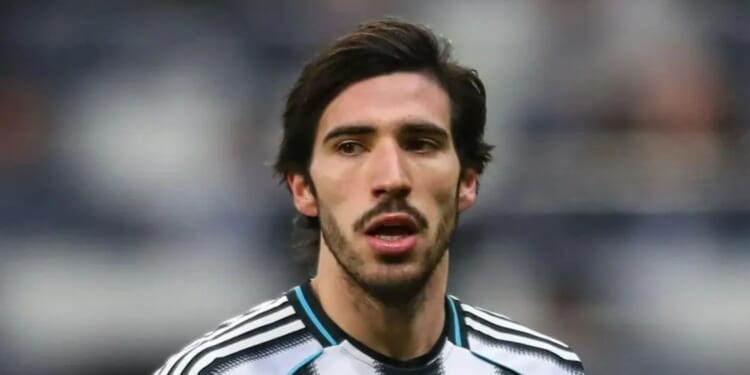

Mr. Lin, for his part, isn’t thrilled about the change. But he accepts it as necessary to sustain the pension system.

“For the younger workers, what’s important is how much they’re getting paid and the retirement benefits,” he says, standing under a wintry sky near the Tangshan Mining Industry Co. factory. “We have to consider the next generation, and not be too selfish.”

But when it comes time for that next generation to retire, their pensions will depend largely on where they were born and live.

Of the more than 1 billion Chinese who participate in the system, about 534 million fall under a plan for urban employees and retirees, such as Mr. Qiao, that in 2023 paid recipients about 3,742 yuan, or $537 a month. Yet another 538 million people – rural residents, including migrants and unsalaried urban workers – qualify for a far less generous plan that in 2023 paid about 223 yuan, or $32 a month. This reflects a fundamental inequality in Chinese society between rural and urban communities.

Civil servants and other government employees receive larger pensions, currently estimated at 6,000 to 7,000 yuan a month, according to a 2025 report by the Berlin-based Mercator Institute for China Studies.

“We have seen … increasing perceptions of unfairness,” and declining faith in China’s meritocracy, Dr. Huang says. People believe their economic well-being is determined by regional disparities, the tax system, and other factors – rather than how hard they work, she says.

Frustration has led pensioners to protest local government cuts to their healthcare benefits in recent years.

Aware of the political sensitivity of pension reform, China’s leaders have moved slowly to address it, despite mounting demographic and economic pressures. Beijing first floated the idea of raising the retirement age more than a decade ago.

Beijing’s goal is to replace the decentralized, regional management of pensions with a national system by 2035.

But its objectives of expanding pension coverage and keeping the system solvent conflict with competing priorities of robust economic growth and employment.

Ultimately, China “needs to spend less on pensions over time,” says Dr. Barr.