ROCK and railways have been music mogul Pete Waterman’s life for more than 70 years.

The Pop Idol judge made millions from the hit factory that turned out a seemingly endless stream of brilliant songs.

But he spent much of the money he earned buying trains — including the world’s most famous locomotive, The Flying Scotsman.

Today, some of his pride and joys will be taking part in celebrations for the 200th anniversary of the first rail service.

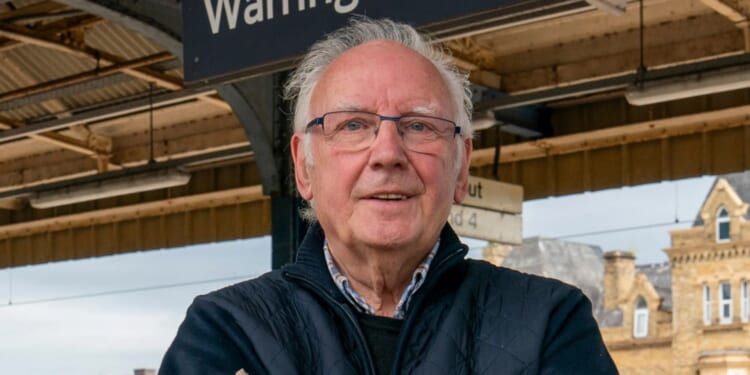

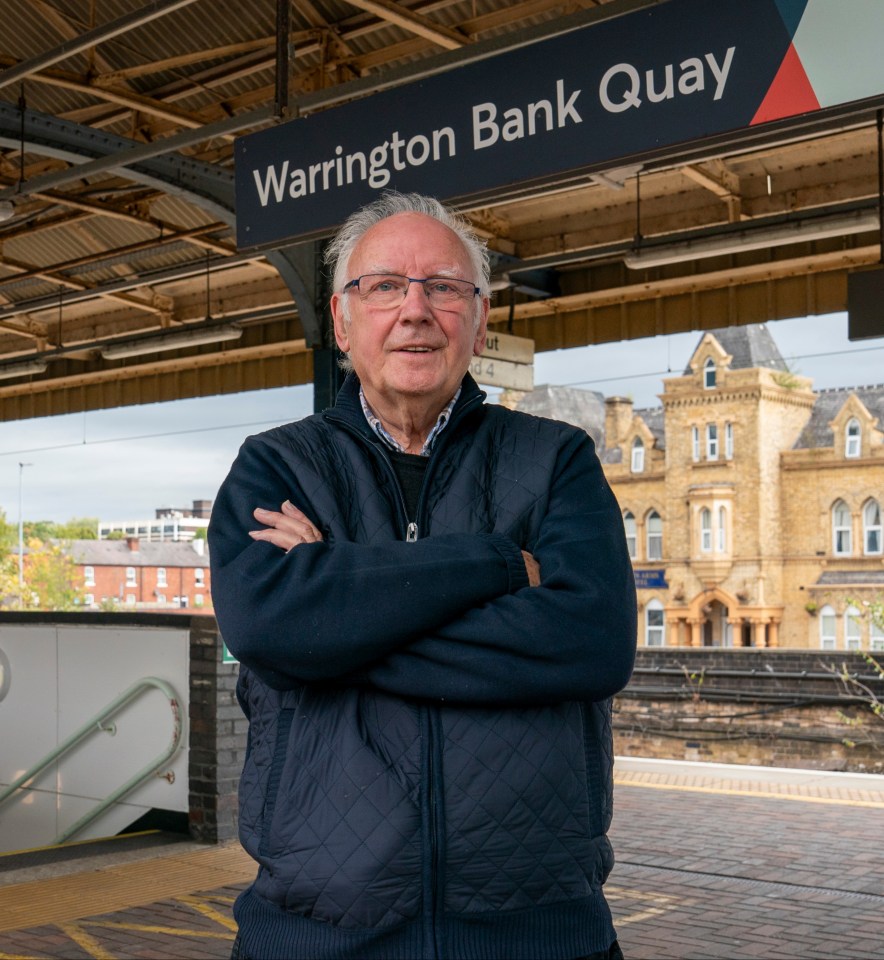

On the platform at Warrington Bank Quay, the nearest station to his Cheshire home, he says: “In one of our discussions, the chairman of British Rail told me, ‘You know what, Pete, the problem is you are too enthusiastic about the railways’.

“There’ll be plenty of time for me not to be enthusiastic when they nail down my coffin lid. Until then I’m going to bang the drum for the railways.”

Pete, 78, is proud to have sent four of his own trains to take part in celebrations, to mark the biggest moment in trans-portation history until the invention of the car.

On September 27, 1825, steam engine Locomotion No1, invented by George Stephenson and his son Robert, puffed 26 miles along the newly opened Stockton to Darlington Railway, carrying 600 joyous passengers sat on top of coal wagons.

Pete has just watched two documentaries made by Michael Portillo, to coincide with the anniversary, and reveals he was first-choice presenter for the BBC’s Great British Railway Journeys, which began in 2010.

He explains: “I was offered that gig but was too busy with our band Steps, so the BBC gave it to Portillo — a typical MP who didn’t understand the railways.

“If I’d been doing those programmes on the 200th anniversary I’d have told the viewers all about the skullduggery that went on in those early railways that were bringing in upwards of a billion pounds.

“George Stephenson was basically a builder who designed the railways, but he didn’t build engines.

“His son Robert is looked at as the father of the modern rail engine, the inventor of Stephenson’s Rocket, but of course he isn’t.

“For a lot of the time he was away silver mining in South America.

“A guy called Timothy Hackworth, a Wesleyan minister, was the man that really developed the steam engine into a powerful tool that worked on the railways.

“Those early railway engines didn’t work. They fell off. They broke down. They blew up.

“Hackworth invented the blast pipe, which forced air through the fire and increased the heat to boil more water, to give you more steam and more power.

“That simple blast pipe that he designed lasted up until 1968 when steam trains stopped being used by British Rail.”

Stephenson gets all the credit for the Rocket but, in fact, it didn’t work. It was useless. It didn’t even get to Manchester on its own.

Pete Waterman on Stephenson’s Rocket

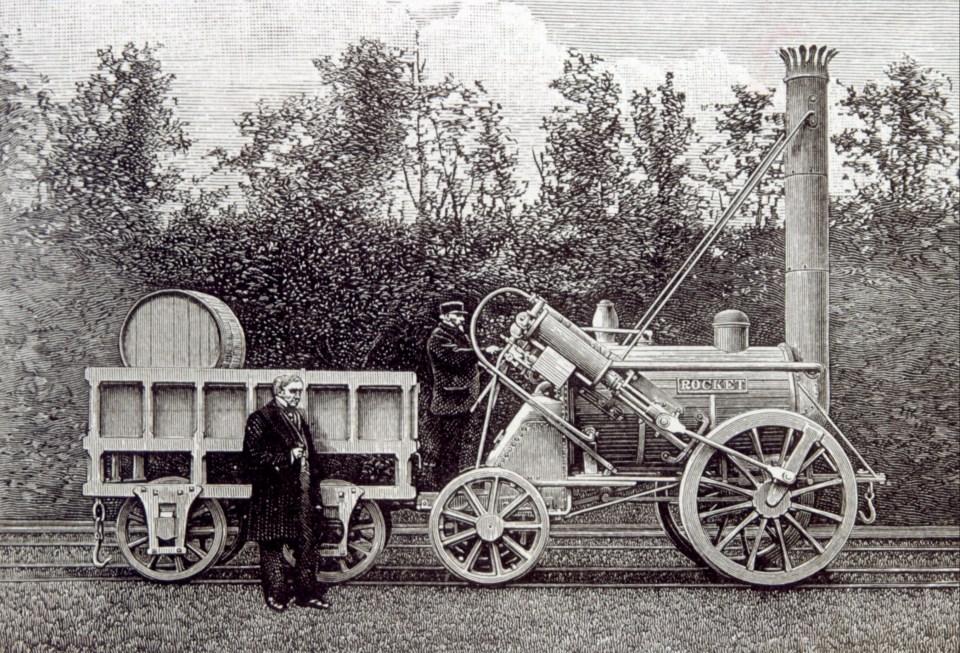

Four years after the launch of the Stockton to Darlington line, trials were held on a mile of track to decide which locomotive would be used on a new railway from Liverpool to Manchester.

Ten locos took part in the Rainhill Trials, including Stephenson’s Rocket and Hackworth’s San Pareil, for a £500 prize.

Pete says: “San Pareil was clearly the best locomotive but the trains had to run for seven days.

“Hackworth being a minister would not work on a Sunday. So, Rocket won the prize.”

Pete adds: “Stephenson gets all the credit for the Rocket but, in fact, it didn’t work. It was useless. It didn’t even get to Manchester on its own.”

At Warrington Bank Quay station we are just along the track from the scene of the first-ever railway death, which happened in 1830 near Newton-le-Willows, Merseyside, during the opening ceremony of the Liverpool to Manchester line.

Pete says: “The victim was the MP William Huskisson, a dock owner, who had fought for the railways.

“He got out of his carriage to shake the hand of the Prime Minister, the Duke of Wellington, who was opposed to letting people travel. Wellington believed the working class should stay where they were and not see life any different.

“Huskisson went over to say, ‘You lost but let’s stay friends’. He grabbed the carriage door which swung open and he got hit by the train going the other way.”

Pete’s 70-year love affair with trains began as a child growing up near the railway in Coventry.

In 1962, aged 16, he went to work for British Rail. But he quit after 17 months to concentrate on music.

It will get finished, railways always do. The sad thing is that I won’t be here to see it.

Peter Waterman on HS2

Today he is President of the Railways Benefit Fund, which looks after rail workers who fall on hard times.

Like Michael Portillo he has a train named after him — an orange and yellow Electric E90 freight train, with Pete Waterman OBE on the nameplate.

By chance, as we are talking at Warrington Bank Quay station, the train named after Pete roars past. On another platform a freight train waits for 40 minutes because there is no room for it further down the line.

Pete says: “That’s why we need HS2 so more trains can travel on our lines.”

He is a big fan of the multi-billion pound HS2 and believes the Chinese — who he says are the greatest train builders in the world — would have finished the line in three years.

Pete says: “It will get finished, railways always do. The sad thing is that I won’t be here to see it.”