The decision you take in the next fraction of a second could save a young woman’s life. But it may destroy yours.

Imagine you’re the first SAS operator ordered into a shopping centre as a terrorist incident unfolds. You burst through the door and a man wielding a machete is bearing down on a young mother, frozen to the spot with fear.

You have a good, unobstructed view of the attacker. Instinct and training tell you deadly force must be used immediately to protect her.

You pull the butt of your weapon into your shoulder and try to shake sweat from your forehead to keep it from dripping into your eyes.

You push out what oxygen you have left in your lungs to prevent your breathing from affecting your aim.

The pad of your index finger is now inside the trigger guard and putting the first pressure on the trigger. The attacker is just two paces away from his victim, swinging his blade, as she raises her arms to ward off the blow.

But, in the back of your mind, there’s doubt.

If you take the shot before that weapon has made potentially lethal contact, is there a possibility you will face criminal charges for ‘disproportionate’ use of force?

Andy McNab served nearly 18 years in the Army from 1976 to 1993, including ten years in the SAS and two years with the special reconnaissance unit, 14 Intelligence Company, as an undercover operator

Will the chilling threat of a conviction hang over you for decades while an inquiry panel decides what you could and should have done instead? Will your family life and professional future crumble to dust?

So, do you open fire? Or do you wait one more second until the blade hacks into the young woman’s arms?

You may feel that sounds far-fetched. Surely any soldier so uncertain about taking immediate action has no place in our special forces.

Sadly not. Relentless hounding by the courts is making it impossible for the SAS to do its job.

Earlier this month, the Commons held an emotional debate over Labour’s disastrous plans to repeal part of the Legacy Act, which could lead to prosecutions for former British soldiers who served in Northern Ireland, and which the Daily Mail is bravely campaigning against.

First to face renewed investigation are likely to be the SAS troopers who intervened to prevent carnage when an IRA squad prepared to plant a bomb and open fire on Loughgall police station, County Armagh, in May 1987. Eight terrorists were killed, as well as an unfortunate bystander in his car.

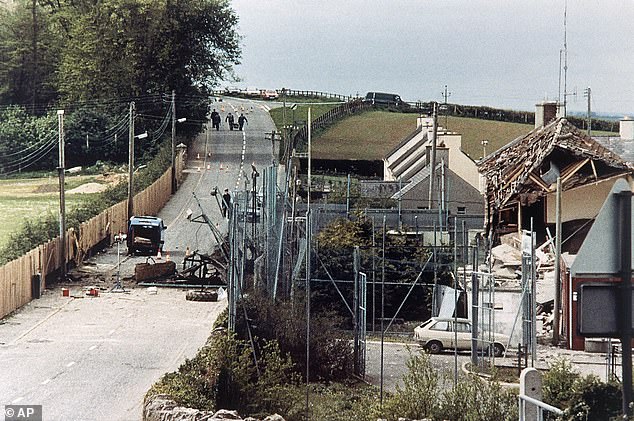

The SAS troopers who intervened to prevent carnage when an IRA squad prepared to plant a bomb and open fire on Loughgall police station (pictured), County Armagh, in May 1987, will likely face renewed investigation

Eight terrorists were killed, as well as an unfortunate bystander in his car, in the aftermath of the bombing of Loughgall police station

One of the allegations against the soldiers is that they used undue force; some of the terrorists were shot several times.

There’s a simple operational reason for that: these were very dangerous men and they were heavily armed. Once the SAS were in contact with the terrorists, they had no choice but to ensure the targets were dead. Not wounded, and so in a position to return fire – dead.

In close-quarters fighting, two shots are usually required to make certain of a kill. But this was not a close-quarters fight. British special forces do not keep firing into bodies without very good cause. They needed to be certain.

I served nearly 18 years in the Army from 1976 to 1993, including ten years in the SAS, with multiple tours in Northern Ireland. As both an infantryman and in the special forces, I served in South Armagh, Belfast and across the province.

This included two years with the special reconnaissance unit, 14 Intelligence Company, as an undercover operator. My role was to fade into the background, watching suspected terrorists and trying to discover what they were planning.

We learned to look for the smallest hints. In Gibraltar in 1988, for instance, we picked up intelligence that three IRA terrorists were planning a car bomb attack on British military personnel.

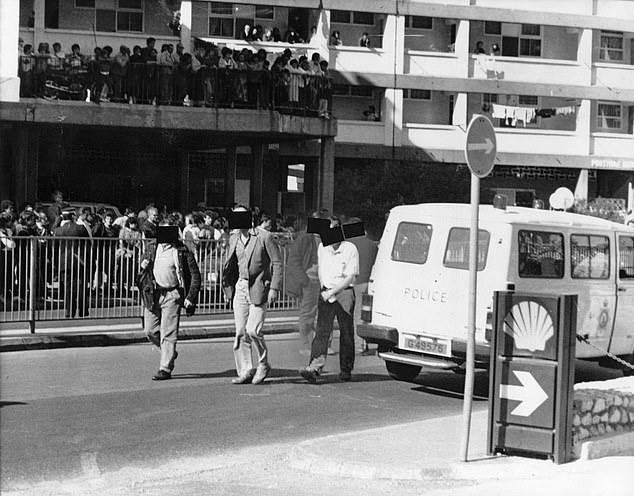

Security men, believed to be SAS, leave the scene of the shooting of IRA terrorists suspected of planning a car bomb attack on British military personnel in Gibraltar in 1988

Daniel McCann, along with two other members of the IRA, Sean Savage and Mairead Farrell, were shot and killed by the SAS in Gibraltar

One of them, an explosives expert called Daniel McCann, had what poker players call a ‘tell’: when he got anxious, he broke out in acne. And in Gibraltar in March 1988, his skin was flaring up badly. He might as well have worn a T-shirt that said: ‘I’m planning a bomb attack.’

That attack involved 140lb of Semtex. McCann was shot dead by the SAS, along with his murderous confederates Sean Savage and Mairead Farrell.

The use of prompt, efficient, deadly force unquestionably saved numerous lives. But the episode has been the subject of Left-wing criticism ever since.

As a member of 14 Int, my role was not to take part in the ambushes. That would have blown my carefully constructed cover. Instead, I pointed out the target before melting away.

But, to do that, I had to make sure I wasn’t pointed out first. And in the tight-knit communities of Northern Ireland, that was very challenging.

It helped that I’d grown up on a tough housing estate myself. Anyone who hasn’t will be betrayed immediately by their body language – they’ll feel like they’re in alien territory, and that will show.

The first people to spot it, we learned, are mothers with small children. They’ve got a sixth sense for men who don’t fit in.

And then there are the children themselves. They’re known as ‘dickers’, and, playing out on the street, they see everything and report back. That eight-year-old with a cheeky grin, kicking a ball with his little sister? Either of them could get you killed.

On one operation, I was in the Bogside housing estate in Derry, watching these guys who were preparing an attack with a rocket-propelled grenade on an Army patrol.

They had a system: take over a house, one with no known links to terrorists, and lie in wait. I needed to know which house they’d picked.

The estate was a maze of 1960s buildings. It looked like someone had emptied a box of Jenga bricks over the district. Taking a wrong turn was all too easy.

My cover story was simple. If anyone asked, I was ‘visiting my brother-in-law’.

But that implied I knew my way around. And when I turned up one alleyway and discovered it was a dead end, I knew I was in trouble.

I glanced over my shoulder. A little band of dickers was stood at the entrance to the lane, watching me with undisguised suspicion.

There was only one plausible reason for a lone man to take a detour up a blind alley. I scowled at the kids, turned my back on them and pretended to take a leak. Then I sauntered back, zipping up my fly.

If they’d seen I was faking, my day would have ended badly – bundled into a van at gunpoint, tortured and beaten to death, my corpse dumped at the roadside as a warning.

Andy McNab asks why the country that the SAS risk their lives to protect is now hounding them through the courts

Why would any soldier take risks like that if he fears his own government will drag him through the courts and perhaps send him to prison – just for doing his duty?

We have a word for the lawyers, coroners and politicians who think they have a right to judge what soldiers do in the battlespace. We call them ‘the Crowd’.

Decades after the event, the men and women of the Crowd sit in their air-conditioned offices, sipping mineral water, and decide what the SAS could and should have done while dealing with a life-and-death situation.

With the dark humour typical of the military, we joke about people in the Crowd. They’ve got shoulders like Coca-Cola bottles, we say – responsibility just slides off.

The SAS is not a knitting circle. Its troops are selected, trained and prepared to defend our country and its values – professionals sent to carry out tasks that can involve killing or being killed.

So why is the country that the SAS risk their lives to protect now hounding them through the courts?

- ANDY McNAB – CBE, DCM, MM – is a former SAS soldier and the bestselling author of Bravo Two Zero.