AN ANCIENT sword engraved with swastikas and forged long before Jesus walked the Earth has been discovered in a Celtic Iron Age necropolis.

Uncovered intact in France after 2,300 years, the sword was found alongside one another, both still inside their scabbards.

The sword adorned with swastikas has an ornate, copper-alloy scabbard designed to be worn at the waist.

The blade is covered with decorative engravings.

X-rays also revealed a circle and a crescent moon inlay on the top of the blade.

Its edges are decorated with several polished gems, with at least two gems having swastika designs engraved, according to the French National Institute of Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP).

Swastikas are infamously tied to the Nazi regime and the atrocities of World War II.

Today, the symbol is largely seen as a one of hate and intolerance, and is banned in many European countries, including Germany.

Yet the motif had vastly different connotations in ancient times – and has been found all over the world.

It used to be a mark of good fortune, luck, health and prosperity – which explains why soldiers might want the symbol at their side.

Swastikas were widely used across the Mediterranean, but were picked up by the Celts in mainland Europe towards the end of the fifth century and part of the fourth century BC, according to Vincent Georges, an archaeologist associated with INRAP.

Although Georges told Live Science that he is unsure of what the swastika meant to the Celts.

A team of archaeologists, including Georges, found the two swords among a treasure trove of ancient artefacts in 2022 in the small French town of at Creuzier-le-Neuf.

The second sword was accompanied by suspension rings which allowed it to also be worn at the waist.

Small shreds of fabric were found alongside it, which archaeologists believe could have come from the soldier’s clothes, a shroud or a case.

The long-lost weapons “have few equivalents in Europe,” Live Science reported, citing INRAP.

The sleepy town of just 1,500 people was once at the crossroads of territorial occupation by the Celtic Arverni, Aedui and Bituriges tribes during the Second Iron Age between 450 and 52 BC.

The bounty included metal ornaments like jewellery, copper-alloy bracelets, and over a dozen damaged brooches.

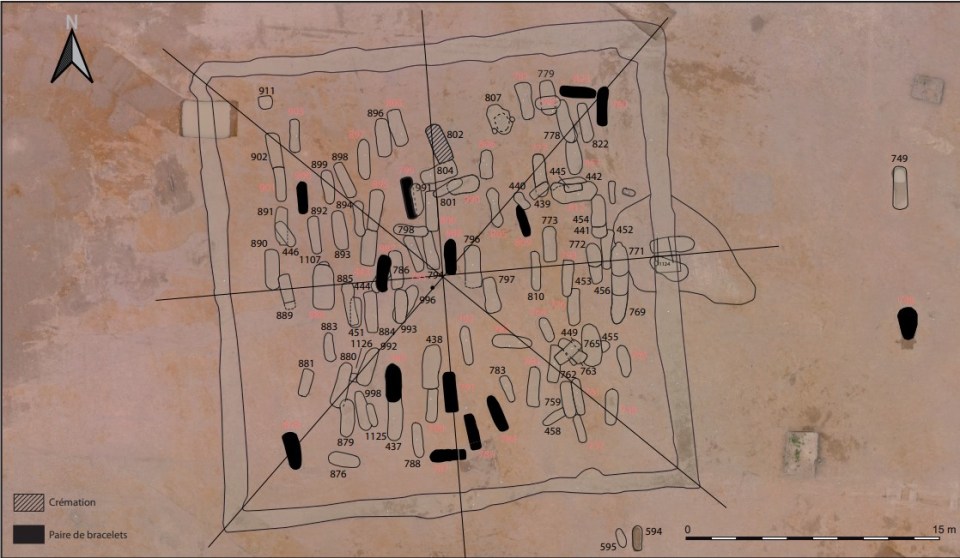

Each item was excavated from a roughly 7,000-square-foot burial area with over 100 graves.

But the region’s acidic soil meant no skeletal remains were found – only a single cremation burial alongside a funerary vase.