Deep in the Atlantic Ocean, scientists have discovered a haunting undersea world that may hold the blueprint for how life began on Earth.

This vast field of mineral towers, called the Lost City, is the oldest known hydrothermal system in the ocean. Scientists believe its extreme conditions mirror the early Earth, offering clues to how the first life forms might have emerged.

The Lost City Hydrothermal Field lie more than 2,300 feet beneath the surface, on the slopes of an underwater mountain in the Mid-Atlantic Ridge.

The Mid-Atlantic Ridge is a massive underwater mountain range that runs through the Atlantic Ocean. It marks the boundary between tectonic plates and is a hotspot for geological activity.

Researchers estimate the Lost City has existed for over 120,000 years, making it the longest-living hydrothermal vent field ever discovered.

In a recent breakthrough, scientists successfully recovered a core sample of mantle rock from the site. This rock is the deep Earth source that fuels the vent system.

The core sample could help scientists better understand the chemical reactions happening beneath the seafloor, reactions that produce hydrocarbons in the absence of sunlight or oxygen, serving as food for marine life.

These same reactions may have played a role in the origin of life on Earth billions of years ago.

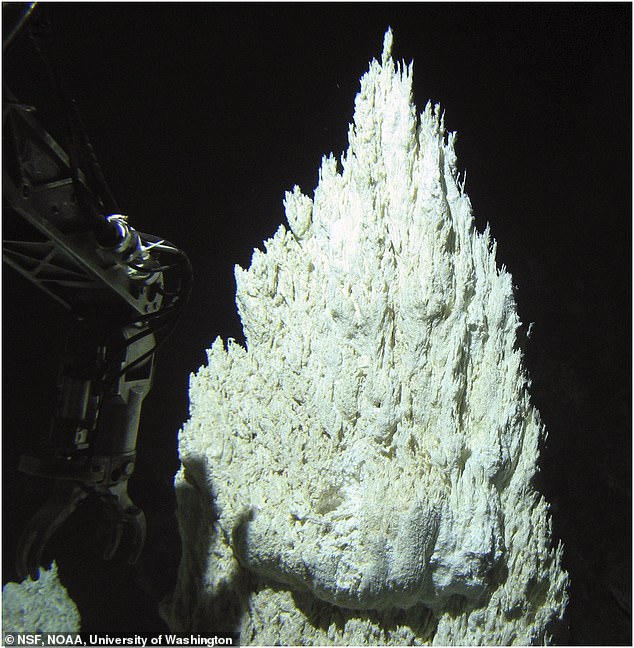

The Lost City is made up of towering spires of carbonate rock, formed by chemical reactions between seawater and hot rock from beneath the seafloor

The Lost City is made up of towering spires of carbonate rock, some nearly 200 feet tall, formed by a unique geological reaction called serpentinization, where seawater interacts with mantle rock deep below the seafloor.

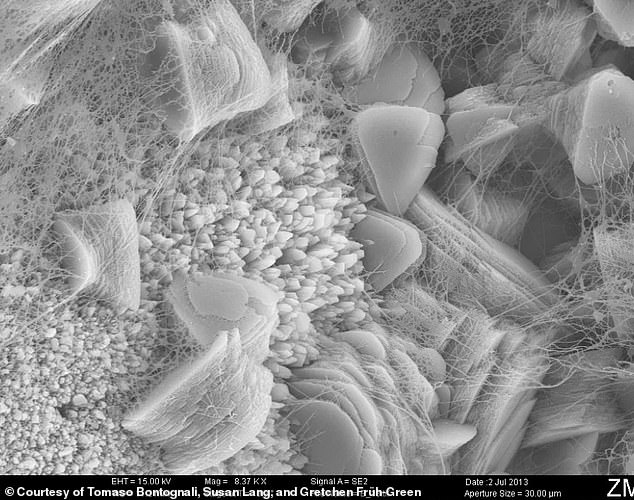

These reactions release methane and hydrogen gas, which fuel microbial life that survives without sunlight or oxygen, something rarely seen on Earth.

The site is located approximately nine miles west of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge axis, just south of the Azores islands.

Its isolated position means it has remained undisturbed by human activity for thousands of years, preserving an ecosystem that offers a window into Earth’s earliest conditions.

Each hydrothermal vent, nicknamed IMAX, Poseidon, Seeps, and Nature emits warm, alkaline fluids. These create a stable environment for life in one of the most extreme corners of the planet.

Now, with renewed global attention, scientists believe the Lost City may help explain how life first formed from non-living matter, an unsolved mystery in biology.

The site is located approximately 15 kilometers (about nine miles) west of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge axis, just south of the Azores. Its remote position places it far from human interference.

Unlike most hydrothermal systems powered by volcanic heat, the Lost City is powered by chemical energy from the Earth’s mantle, giving it a distinct structure and chemistry.

Inside its towering chimneys, fluids reach up to 194 Fahrenheit, not boiling, but hot enough to fuel chemicals reactions.

These vents produce hydrocarbons, organic compounds made from carbon and hydrogen, which are considered the building blocks of life.

The site is special because its hydrocarbons form through deep Earth chemical reactions, not sunlight or photosynthesis. This makes the Lost City a rare second example of how life could begin.

Microbes inside these chimneys live in total darkness, with no oxygen, using methane and hydrogen as their only fuel.

On the outer surfaces, rare animals like shrimp, snails, sea urchins, and eels cling to the mineral-rich structures.

Larger animals are uncommon here likely because the energy supply is limited. Unlike surface ecosystems, there’s no sunlight or abundant food chain, only chemical nutrients trickling out of the vents.

Microbiologist William Brazelton told Smithsonian Magazine: “This is an example of a type of ecosystem that could be active on Enceladus or Europa right this second.”

While the Lost City itself lacks mineable materials, nearby regions could be targeted for future deep-sea mining operations.

These are moons of Saturn and Jupiter, which have oceans beneath icy crusts, raising the hope that similar life could exist beyond Earth.

Some spires have grown to 60 meters tall over tens of thousands of years.

Scientists say they act like natural laboratories, showing how life might arise in environments without sun, plants, or animals.

In 2017, the International Seabed Authority (ISA) gave the Polish government a 15-year exploration license for an area of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, which includes territory surrounding the Lost City.

Though Lost City itself lacks valuable minerals, nearby vent fields may contain polymetallic sulfides, a target for future deep-sea mining. That’s where the threat comes in.

Mining operations near hydrothermal vents can stir up sediment plumes, releasing toxic chemicals or particles that drift through the water column and harm nearby ecosystems, even if the site itself isn’t directly touched.

The Convention on Biological Diversity has already designated Lost City as an Ecologically or Biologically Significant Marine Area (EBSA), based on its uniqueness, biodiversity, and scientific value.

Being listed as an EBSA gives scientists leverage to argue for protective measures, though it carries no binding legal protection. Meanwhile, UNESCO is reviewing the site for World Heritage status, which could offer stronger international backing against mining and disturbance.

Scientists argue this is urgently needed. Once disturbed, such systems may never recover, and we could lose a living example of how life began.