This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

I followed the recent competition to choose an architect to reinvent the British Museum’s Western Range (the run of galleries to the west of the Great Court) with the utmost interest because the range represents by far the most significant part of the museum, housing many of its greatest treasures.

It includes one of Sydney Smirke’s grand neoclassical galleries. Beyond are further galleries designed by Smirke, originally to house the Elgin Marbles. In the 1930s, Lord Duveen paid for John Russell Pope, an American Beaux-Arts architect, to design a monumental, if sepulchral, new gallery to show off the Elgin Marbles as works of art.

Meanwhile, the original galleries were filled in with a set of confusing galleries to house the Greek and Roman collections, which have not been comprehensively redisplayed since the 1970s when the floors were covered with sand-brown tiles by the government’s Property Services Agency.

So, a decision as to who should redesign — and, more especially, redisplay — this area of the museum will have long-term implications for the look and feel of the museum in the future.

The competition was organised by Colander Associates, who have particular knowledge of architects because Caroline Cole, its founder, previously worked as Head of the Clients’ Advisory Service and Competitions Office at the RIBA. The initial selection looked safe and a bit predictable, with one exception.

The oldest and grandest of the architects competing was Rem Koolhaas, now aged 80. His entry is likely to have been prepared by Shohei Shigematsu, who has worked on all of Koolhaas’s recent museum projects from the ill-fated and rejected extension to the Whitney Museum in New York in 2001 to the recently completed extension to the New Museum of Contemporary Art, also in New York.

Their entry was described as “Maximum impact, minimum intervention: transforming two underused, infilled courtyards modernises the functioning and expands the potential of the entire British Museum”.

David Chipperfield Architects would also have been a safe choice. His radical reconstruction of the Neues Museum in Berlin jointly with the conservation architect, Julian Harrap, remains the most intelligent reinvention of a 19th century museum, since which he has been employed on a multitude of museum projects all over the world, particularly in Germany. He has gravitas and is notably sympathetic to classicism.

Jamie Fobert, who worked so successfully with Nicholas Cullinan, now Director of the British Museum, at the National Portrait Gallery teamed up with Eric Parry, another established veteran, responsible for the Holburne Museum in Bath. Fobert started out working for Chipperfield. They proposed the possibility of going up as well as down, creating new staircases near the entrance and new entrances from the Great Court into the galleries to the west, viewing the challenge as one of circulation.

6a are younger than koolhaas, Parry and Chipperfield. They first became known for a lovely renovation of an 18th century shop in Raven Row close to Liverpool Street as an art gallery for Alex Sainsbury and have since worked on the South London Gallery and a new gallery in Milton Keynes.

The fifth architectural practice selected was less obvious. Lina Ghotmeh is a young-ish, Lebanese architect, brought up in war-torn Beirut, where she developed an interest in archaeology and trained in architecture at the American University in Beirut.

She then moved to Paris to work with Jean Nouvel, who was working on the Musée du Quai Branly and later designed the Louvre Abu Dhabi.

In her mid-20s, she won a competition jointly with two of her peers, Dan Dorell and Tsuyoshi Tane, to design the new Estonian National Museum in Tartu. It was, perhaps inevitably, a long drawn-out project, only opening in 2016.

But it must have given her a taste, as well as good experience, of the politics of national museums. The result is much admired, designed to align with the runway of a Soviet-era military airport. Its director is now the President of Estonia.

For the British Museum competition, she assembled a small team, including the conservation architects, Purcell, who have been overseeing the renovation of the Sainsbury Wing, and a firm of museum designers, Lucy Holmes, who did the installation of the Founder’s Galleries at the Fitzwilliam Museum.

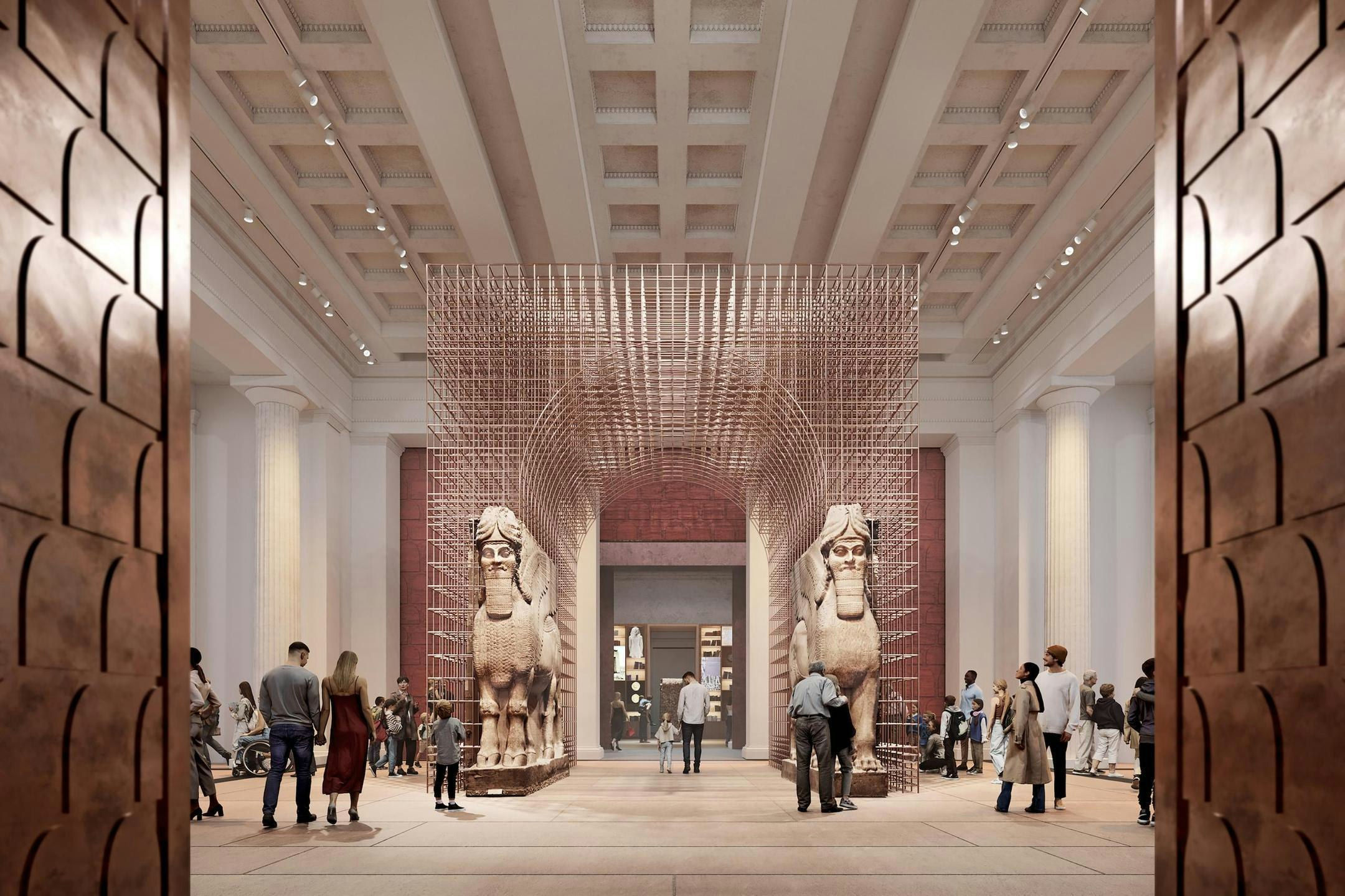

Lina Ghotmeh presumably won the competition because she is young, the same generation as Nicholas Cullinan, and perhaps because her approach to the displays is less predictable than the other competitors. She describes her approach as “the archaeology of the future” — not just the display of objects, but how they are seen and interpreted by audiences.

As she has written, “I am often frustrated by the lack of available information. I want to learn more. I would like more human interaction. An artefact is never stagnant — we build meaning around it.”

She has a gigantic task ahead of her. The project will take ten years at least and is expected to cost up to £1 billion. It is not yet clear whether the galleries will have to close whilst they are renovated.

The problems are not just architectural, but political, organisational and financial: how to manage the enormous flow of visitors; how to engage them with the collection as a whole, not just a few star objects; how to provide information about how and when the objects were acquired.

It will be a huge, politically tricky endeavour; but Lina Ghotmeh looks well qualified for it.