Across the country, many Americans are paying more for their electricity. In Massachusetts, rates increased almost 69% between 2014 and 2024; in West Virginia that number neared 62%, according to EnergySage, an online clean-energy marketplace.

In U.S. cities, electricity costs are increasing twice as fast as other household items, according to a recent consumer price index report for the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. And, on average, the electricity prices for households nationwide are expected to rise 13% between 2022 and 2025, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, the federal government’s authority on energy data.

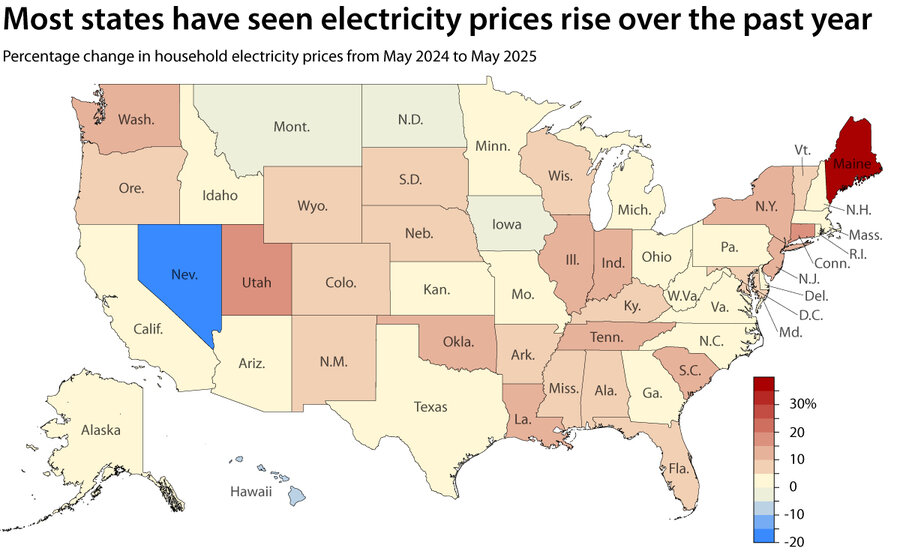

All of this depends on location, thanks to the country’s utility system and how electricity is distributed and sold. While many customers in the Pacific, New England, and Mid-Atlantic regions have been slammed by price increases, other residents – such as those in Nevada – have had stable, or even lower, electric bills.

Why We Wrote This

Rising electricity bills are stinging consumers across the United States. Experts say the trend reflects rising demand for electricity – including from AI – but also the need for upgraded and more adaptable power grids.

Overall, though, the trend has been upward. Part of this is basic economics: There is more demand for electricity. The price of one key fuel for power plants, natural gas, has also jumped. But there are other reasons, as well. And experts say there are also solutions.

Is demand for power rising?

The short answer yes; we are using more electricity. This might be because of more air conditioners running during more heat waves, which in the United States have been steadily increasing since the 1960s. It’s also because of the trend of electrification – from battery-operated lawn mowers to cars – and the rising use of electric heat-pump systems for heating and cooling homes.

But a big new factor is data centers.

As the use of artificial intelligence expands, it’s being powered by the growth of enormous new data centers, which can use as much electricity as a small city. The number of U.S. data centers roughly doubled between 2021 and 2024, and experts predict these centers could account for 5% to 9% of U.S. electricity generation by 2030.

Companies such as Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Meta are investing more in training and running AI programs like ChatGPT. These programs are very costly in terms of energy; AI internet searches use 10 times more electricity than traditional searches.

“We’ve never seen additional load coming on at this scale,” says Melissa Whited, vice president of consulting at Synapse Energy Economics. “Demand is spiking, but supply has not been able to catch up.”

If a utility has to build more power lines or power plants to get electricity to data centers, those costs are typically spread across their customer base – the same way any grid-upgrade costs get distributed to consumers.

“There’s no way to allocate those costs just to the data centers,” says Ari Peskoe, director of the Electricity Law Initiative at Harvard Law School. “Everybody pays for those cost increases.”

For example, PJM Interconnection – a grid operator that covers a region stretching from New Jersey to Chicago to North Carolina – holds a yearly auction to make sure it will have enough supply to keep the lights on for all their customers. In 2024, the value of that auction spiked up to 800% of its value the previous year.

Monitoring Analytics, a watchdog charged with monitoring PJM, calculated in June that data centers were responsible for nearly 70% of that increase.

What about the supply side?

Many experts say that U.S. power grids need updating because of both their aging infrastructure and the need to adapt to a changing mix of power sources.

The years after of World War II saw massive electricity growth, and many existing power plants date back to that era. The result is that much of the U.S. power grid is starting to become outdated. Meanwhile, reliance on coal-fired plants has been diminishing in favor of renewable sources that often supply power intermittently (such as when the sun is shining, for solar power). There have been challenges with both permitting new power facilities and connecting them to aging grids.

American Electric Power, one of the largest electricity companies in the country, has said that 30% of its transmission lines will need to be replaced over the next 10 years. The Department of Energy has found that almost 70% of transmission lines are near the end of their useful lifespan. This can leave them vulnerable to cyberattacks and increase the risk of power outages, as an increase in electricity demand from growth in manufacturing, massive data centers, and electric vehicles puts pressure on an already strained system.

Are there solutions in sight?

Experts see a number of steps that could expand power supply and grid reliability.

One example: Both political parties are working toward streamlining the process of bringing new energy sources online. Currently, a cumbersome permitting process has resulted in a yearslong backlog in adding new energy sources to the grid, much of it solar and battery storage. Lawmakers hope reforming that process will help the supply side of the electricity cost issue.

But many improvements to electric grids take time – and might cost in the short term.

According to the Department of Energy, major electricity outages caused by natural disasters have increased by almost 80% just since 2011. These events can force costly repairs to the electric grid. From 2019 to 2023, the California Public Utilities Commission authorized the state’s three largest utilities to collect $27 billion from ratepayers to cover wildfire prevention and insurance costs.

Many service providers are also trying another option: “hardening” the grid to make it more resilient to disasters in the first place. In California, utilities are paying to move power lines underground so they’re not at risk of sparking and causing wildfires. Electric companies in Florida are switching to concrete poles, clearing trees away from power lines, and installing advanced technologies to be more hurricane-ready.

When it comes to data centers, Severin Borenstein, the faculty director of the Energy Institute at the Berkeley Haas School of Business, cautions against reading too much into forecasts of spiking electricity demand and costs. AI development can be uncertain and difficult to predict, he says.

He also believes policy solutions could stave off some of the high costs. For example, on Aug. 4, Google signed agreements with two utilities to reduce its AI data power consumption during times of peak demand on the electric grid. Dr. Borenstein says it’s a step that gives him tentative optimism. Also, companies such as Amazon are investing heavily in next-generation clean energy solutions, such as small modular nuclear reactors, which could help power their operations.

“Grid operators and regulators, I think, are getting smarter about this,” he says. “Developing these policies, though, is not something that happens overnight.”