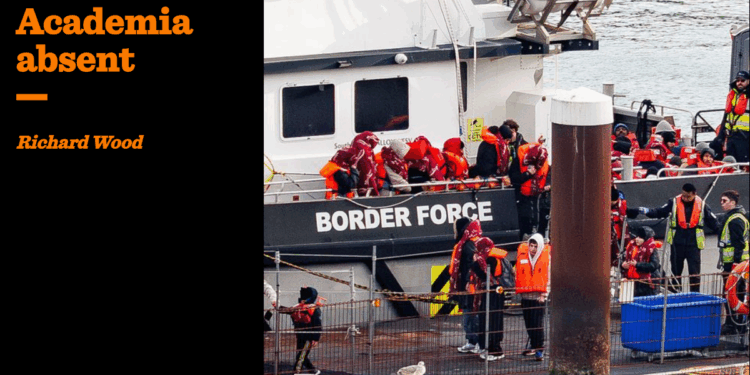

Last month I was pleased to publish the first scientific paper modelling the factors affecting small-boat migration across the English Channel. The research, published in a leading international migration journal, made a number of findings.

First, it confirmed, but quantified for the first time, the pivotal effect that weather and sea conditions have on the viability of crossings, e.g., the odds of an unviable day almost triple for every 10cm of wave height. Second, it found strong evidence that deterrents really do work, e.g., repealing the Dublin III regulation in 2021 was associated with 41 per cent higher arrivals with numbers dropping by 36 per cent following the Albania returns agreement of 2022.

This work helps to address a critical information gap in this domain. Only in July this year the House of Lords heard how “we clearly need robust information and evidence about which factors are actually influencing these movements”. This is remarkable given the small boats started arriving over five years ago and this has been a leading political priority ever since.

The UK is a research powerhouse … Yet, very few have considered the small-boats problem

But why has there been an information gap? And why was I the first one to this problem? After all, migration studies are not my day job. The prospect of applying sophisticated analytical models to high-profile and previously-unsolved problems would traditionally stimulate flurries of academic interest, and yet there has been almost nothing.

The UK is a research powerhouse — every week hundreds of papers get published, from the important to the obscure. Yet, very few have considered the small-boats problem. Those that do have approached it from moral and human-rights perspectives, and have largely called racism and xenophobia. Papers have also levelled curious assertions at government efforts to stem the crossings, likening them to “the active remaking of colonial modes of rule”. Almost nothing has been published objectively assessing the factors at play within this problem.

Perhaps therein lies the issue: consideration of this matter as a “problem”. That the academic community is generally left-leaning will come as news to almost no-one. It is therefore not inconceivable that this matter is regarded as “off limits” for the sake of moral unease of would-be investigators; that any information produced could be used as the basis for government policy-making, leaving feelings of culpability for any resulting actions. Like Oppenheimer’s dilemma when developing the bomb, minus the grave consequences.

Is it right to feel this way? From its earliest origins, academia has been characterised by the pursuit of knowledge for its own sake. There is an argument for academic purity as simply closing gaps in knowledge, with neither fear nor favour to the implications. Otherwise, who arbitrates right or wrong in deciding what matters get studied?

As payer, the government can exert some influence, which it does by funding offered through the research councils. However, it could be argued that some of the same left thinking has taken hold here too, with many funding calls now requiring “inclusive research” and “tackling inequity”. These aspects are not just conveniently left open to the political inclinations of similarly-minded researchers, but are moreover themselves the very product of a particular political mindset. Inevitably, this gives rise to academic journals such as ‘Whiteness and Education’, which seeks papers that “explicitly deploy critical whiteness, anti-racist, anti-imperialist, and anti-capitalist frameworks to disrupt whiteness and coloniality“. Plenty of room for all sides of debate then.

Returning to small-boats, we see research funded by the Economic and Social Research Council regarding deterrents as “fantasies” that “reproduce racialised and colonial logics and ultimately serve border imperialism”. The ESRC is taxpayer funded. Are examples like this really in the public good?

The current state of affairs can feel at odds with what government purportedly expects of academia. In its Research, Development and Innovation Strategy published in March this year, the Home Office pledges strong collaboration with academia which “must be focussed” on department priorities, with specific reference given to “reducing illegal immigration”.

If the government is serious about this then it should get a better grip on the mechanisms through which it funds research. It should promote the unfettered pursuit of knowledge and ensure that, where necessary, any political influence comes only through democratically-accountable channels in steering the areas of research for the purposes of public good.