Have you ever heard of someone so principled that he quit his job rather than do something he knew to be wrong?

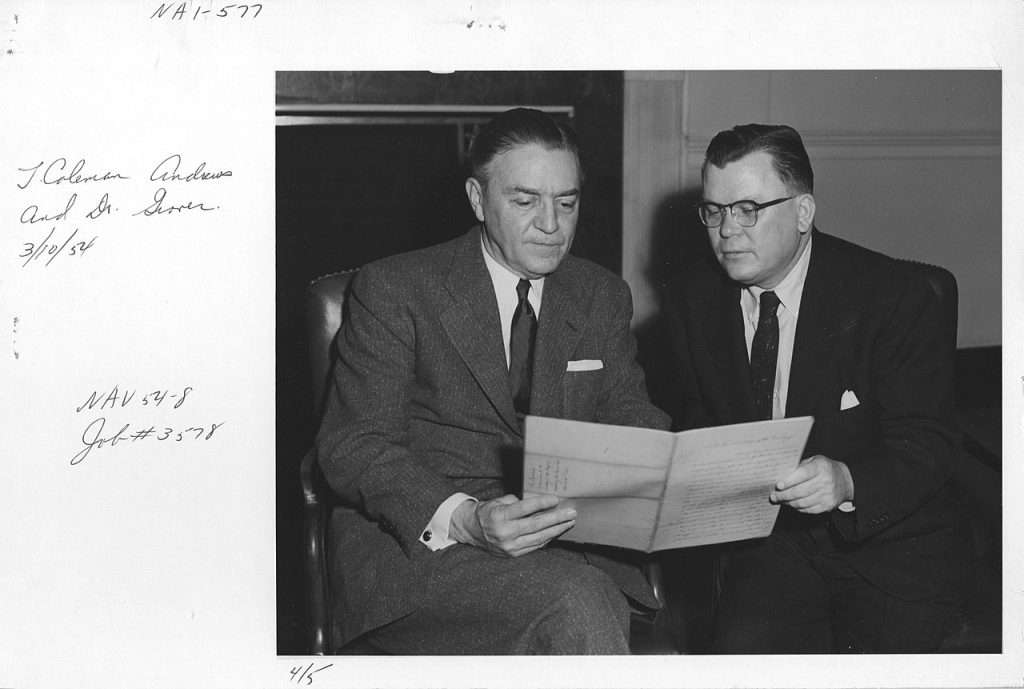

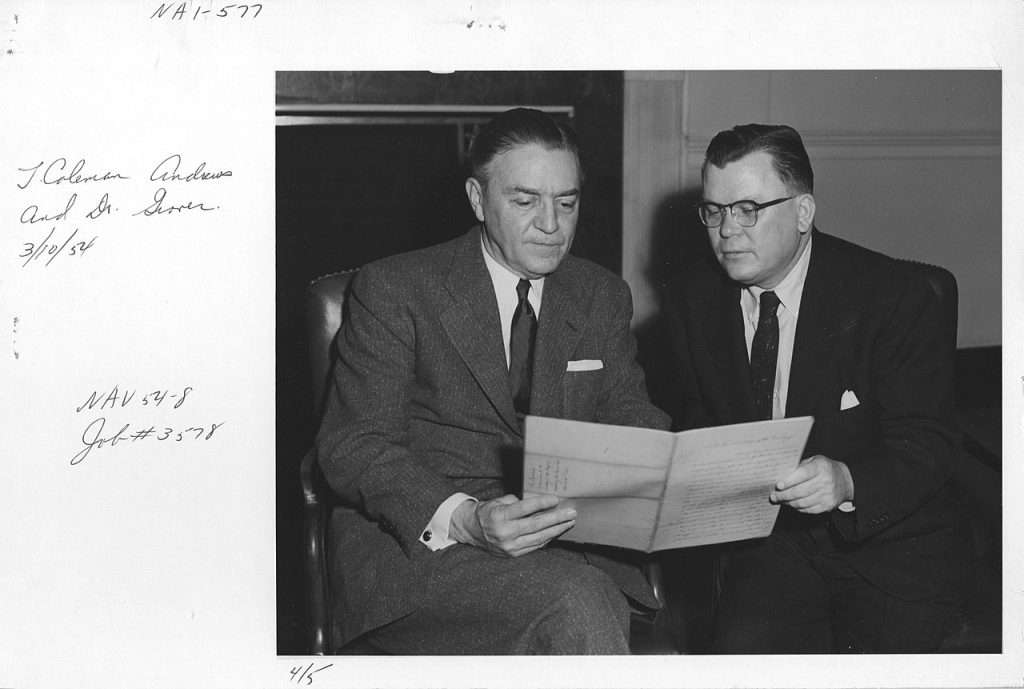

I admire people of such integrity. We need more of them. Let me tell you about one whose story is especially relevant on April 15, the date the federal government demands we meet our income tax obligations. This man was head of the IRS. His name was T. Coleman Andrews.

Born in Virginia in 1899, Andrews possessed a head for numbers. He loved accounting, an affection which I personally could never understand. Accounting baffled and frustrated me during my undergraduate days; I scraped by with a “C.” I agree with whoever described an accountant as “someone who solves a problem you did not know you had in a way you don’t understand.”

Andrews was not only good at it, but he also founded several successful accounting firms and worked in high accounting positions for the Commonwealth of Virginia, the US State Department, and the General Accounting Office in Washington.

In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower appointed him Commissioner of the Bureau of Internal Revenue. In an interview while still new in the job, Andrews said that he would insist that every employee engage taxpayers with “a sincere desire to be helpful,” but he promised to come down hard on anybody caught cheating on his taxes.

Andrews moved to simplify complex tax forms. He changed the Bureau’s name to what we know today—the Internal Revenue Service. He adopted numerous measures to improve efficiency, but when Congress overhauled tax law in 1955, he realized how “unreformable” the system was. Isaac William Martin, in his 2013 book titled Rich People’s Movements, quotes Andrews as lamenting that the congressmen who wrote the bill “do not themselves know what they mean.”

Barely two years into his tenure on the inside, Andrews abruptly resigned. His views on the agency and the income tax had evolved. Andrews was one of those rare public servants who “grew in office.” He could no longer hold a position that put him at odds with his conscience. He came to see the IRS and the tax code as oppressive, incomprehensible, and corrupt. Shortly after his departure from the IRS, he issued a statement explaining his position:

Congress went beyond merely enacting an income tax law and repealed Article IV of the Bill of Rights, by empowering the tax collector to do the very things from which that article says we were to be secure. It opened up our homes, our papers and our effects to the prying eyes of government agents and set the stage for searches of our books and vaults and for inquiries into our private affairs whenever the tax men might decide, even though there might not be any justification beyond mere cynical suspicion.

The income tax is bad because it has robbed you and me of the guarantee of privacy and the respect for our property that were given to us in Article IV of the Bill of Rights. This invasion is absolute and complete as far as the amount of tax that can be assessed is concerned. Please remember that under the Sixteenth Amendment, Congress can take 100% of our income anytime it wants to. As a matter of fact, right now it is imposing a tax as high as 91%. This is downright confiscation and cannot be defended on any other grounds.

The income tax is bad because it was conceived in class hatred, is an instrument of vengeance and plays right into the hands of the communists. It employs the vicious communist principle of taking from each according to his accumulation of the fruits of his labor and giving to others according to their needs, regardless of whether those needs are the result of indolence or lack of pride, self-respect, personal dignity or other attributes of men.

The income tax is fulfilling the Marxist prophecy that the surest way to destroy a capitalist society is by steeply graduated taxes on income and heavy levies upon the estates of people when they die.

As matters now stand, if our children make the most of their capabilities and training, they will have to give most of it to the tax collector and so become slaves of the government. People cannot pull themselves up by the bootstraps anymore because the tax collector gets the boots and the straps as well.

Clearly, this was a guy who didn’t allow power or a paycheck to turn either his brain or his spine into jelly. Agree with him or not, you must admit there’s some impressive personal character there.

Andrews continued to speak out against the income tax and the ever-bigger government it was financing. In 1956, he even ran for President of the United States on a third-party ticket—a campaign that, controversially, was built around a states’ rights platform. While some saw it as a principled stance for limited government, others rightly noted its alignment with political figures and movements that defended segregation. He died in 1983 at the age of 84.

The school in my native state of Pennsylvania where I struggled in that accounting class more than a half-century ago is Grove City College. In researching this article, I was proud to learn that in 1963, GCC bestowed an honorary doctorate upon T. Coleman Andrews.

What Andrews had to say may not be much consolation to you this tax season. Perhaps it will be of at least small comfort, however, to know that we once had an IRS Commissioner who saw the harm of the whole business and possessed the courage of his convictions to wash his hands of it.

Additional Reading:

Why Did Eisenhower’s IRS Commissioner Think the Income Tax was Evil? by Joseph Thorndike

A Few Words From an IRS Commissioner Under Eisenhower by James D. Best

Rich People’s Movements by Isaac William Martin

Tax History: Ike’s IRS Commissioner Called the Income Tax “A Devouring Evil” by Joseph J. Thorndike

Vivien Kellems: “Please Indict Me!” by Lawrence W. Reed

Joe Louis: Fighter on Many Fronts by Lawrence W. Reed