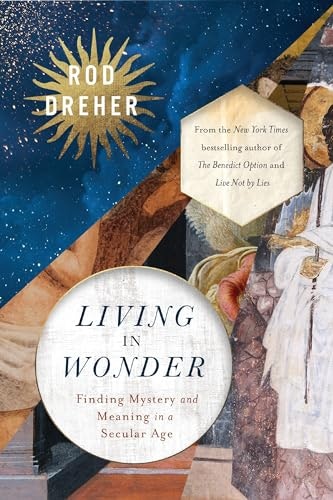

Some years ago, one of Rod Dreher’s friends urged him to write his “woo book”, which is to say, a book about the supernatural side of Christian belief, and this is it. A “work of remembrance, recovery, and healing”, it is also deeply personal. Teeming as it is with stories of people’s personal encounters with the living God, which are ensconced in the author’s characteristically intellectual wonderwork, it is a real treat.

Historian Tom Holland, author of Dominion: The Making of the Western Mind (2019), has said in recent years that “the call of our time” in the West is to “Keep Christianity Weird”. Enter Dreher, self-proclaimed “weird magnet”, with his stories of signs and wonder. Harvard anthropologist Joe Henrich has suggested that the Western world, in a quite different sense, is WEIRD: Western, educated, industrialised, rich, and democratic. The way Western man and woman views the world has shifted since the onset of modernity, and in this context, Rod writes, “Churches need to lean heavily into the supernatural, the woo”.

The watchword of the day for the likes of Tom and Rod and Joe has shifted in the last half decade or so from community to disenchantment. Recently, I heard Rod talk about his book in conversation with Ian McGilchrist, “one of the heroes of this book”, at the Oxford Literary Festival at Pusey House, which is the Anglo-Catholic Chaplaincy to the University of Oxford. I first read Rod’s most well-known book The Benedict Option (2017) — all about building faithful communities — when I was Lay Pastoral Assistant to the House in 2020. Its thesis is that we can learn from Benedictine monasteries in how Christians engage with mainstream culture, and at that time a colleague who oversaw Oxford’s Scriptorium, a study group modelled on the study room assigned to medieval monks, wrote that the word “community” was now “so overused” but little valued, even less so understood.

The same is now true of “disenchantment”. Rod does not like the word “enchantment” so far as it makes people “think of something very precious”, such as sprinkling “the mundane world with mental fairy dust to make it more interesting”, or worse of the occult, which is those beliefs and practices outside of organised religion. He defines it as the “confident belief” that “God is everywhere present and fills all things”. As such, to re-enchant the world is to recover “a way of feeling God’s visceral presence among us” within the woo and the view that there is a “deep meaning to life, independent of ourselves”. This will take place at a time when “our common culture”, unlike any true community, denies that we can find meaning anywhere at all.

My frustration with The Benedict Option was two-fold. Firstly, I was one of those who wrongly assumed that the book was encouraging Christians to head for the hills. Inspired by Alasdair MacIntre’s After Virtue, he wrote, Christians in the western world “have to develop creative, communal solutions to help us hold on to our faith and our values”. This was reviled as retreatist. Alongside this, the book’s “Strategy for Christians in a post-Christian Nation” failed to deal adequately with the question of meaning in its discussion of life at home, education, work, love, and “Man and the Machine”. This was a work of sociology, of structure, lacking in spiritual substance.

Living in Wonder is Rod’s spiritual coming out. In it, we are told how “everyday bumblers like me” encounter and are enchanted by the risen Lord. The book began its life in an encounter Rod had with an artist on the last night of The Benedict Option’s book tour, and this is apt because The Benedict Option itself is re-enchanted, brought alive as it were, in the light of Living in Wonder. Likewise, community arises exclusively from communion, being that place where we are lost in the divine love. Rod knows, The Benedict Option is only ever an option in this context.

The way to rebuild and re-value community is to allow oneself to be re-enchanted again and again

In speaking of enchantment, at the Oxford Literary Festival, Rod referenced the work of Alfred Tomatis, who was a French physician, psychologist, and ear specialist in the mid-twentieth century. In a study of how chanting magnetised Benedictine monks, he noted that when a new abbot chomped down on chanting within one such monastery, the brethren became tired and lethargic. Like so many of us today, bumbling along, the monks learnt that disenchantment entails decline in communities in which we care for one another. The way to rebuild and re-value community is to allow oneself to be re-enchanted again and again.

If anyone wants to know how to do so, reading Rod’s book would be an excellent place to start. It is disappointing in its concurrence with Paul Kingsnorth that England has lost out on the mystical since the Reformation and is now “marooned” in the “civilizational shipwreck of the modern West” — not so. Rod was full of praise for the Anglo-Catholic wing of the Anglican Communion at the Literary Festival, going into evensong. Eastern orthodoxy is not the only place that one can be enchanted. Notwithstanding, read Rod’s book.

Learn from the company of voices there and from Rod’s own road to spiritual recovery. In it he quotes the Canadian communication theorist Marshall McLuhan, a devout Roman Catholic, who wrote “The medium is the message’” Never was it truer than with this book.

Everyone mentioned knows what it is like to live in wonder. They testify to the same, through a kind of chant flowing off the page, and through them, all of us can find mystery and meaning in a secular age.

So, it was apt that the woman sitting next to me on my train interrupted me, at this point, to ask me if she should get a copy. “Yes!”

I encourage you to find yourself a copy too to better participate in the “pulsating centre of life in Christ”. And I hope that you too shall be lost in wonder; lost in love and praise.