This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

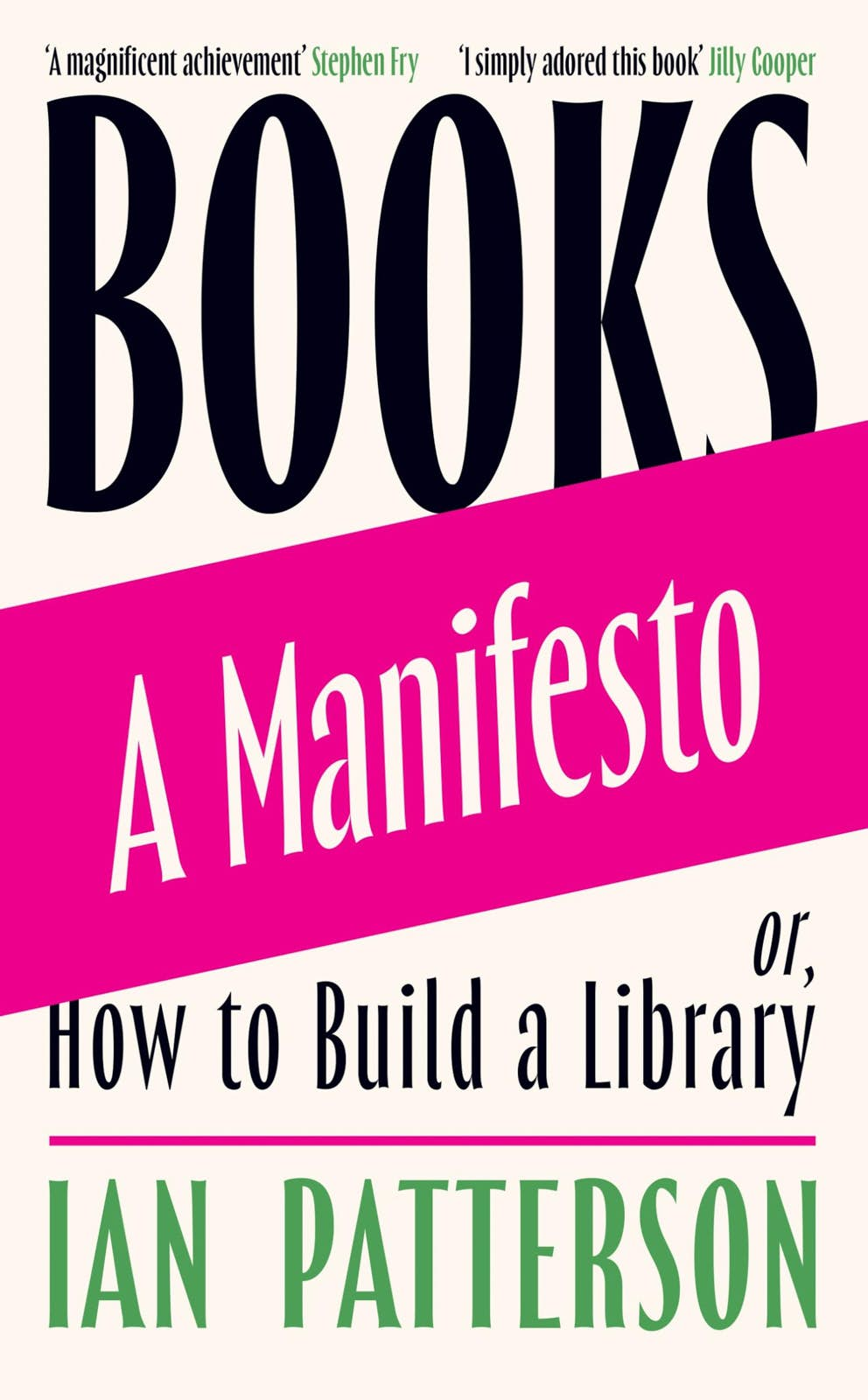

“A personal library is the archive of a life.” So claims the poet, academic, translator and former bookseller Ian Patterson in this memoir of a life spent in and around books. Whilst libraries were once widely seen as the essential means by which a person could navigate and interpret the world, nowadays they are more typically deemed an optional supplement to good WiFi. This, for Patterson, is a crisis that must be addressed. In his captivating survey of his own library, he insists that our need for physical books is greater than ever.

Patterson’s reasoning is by turns practical and ideological. He notes that, after the 2023 cyberattack on the British Library, “the advantage of the material object ought to be obvious, despite the space each book needs to occupy”. For him, books are imperative for the proper functioning of society: reading “helps people find their own voice, work out for themselves what they think, on the basis of actual evidence, and gives them the confidence to articulate it”.

This is why autocrats burn books, Patterson tells us. As AI tools cheerfully spout nonsense and misinformation, and extreme political movements employ censorship around the globe, libraries can be a bulwark against groupthink. They are “a work of resistance, as well as a work of civilisation”.

Reading is for Patterson a radical act. His take on the value of reading is compelling because it is grounded in his own experience and accumulated wisdom about literature. He decided to write the book after he and his wife (the writer and fellow radical Olivia Laing) moved to a new house during the pandemic: in each chapter, he chronicles the project of constructing a library there.

As he surveys the volumes he possesses and remembers those he has lost or given away, Patterson realises that each book we own is a reservoir for memory. He traces each stage of his life through literature, from his childhood discoveries of J.R.R. Tolkien and A.A. Milne to later passions as a poet, translator and teacher.

In taking stock of his reading life, Patterson demonstrates how our relationship to books changes with age. As children, we read to lose ourselves and to glimpse other worlds: we enter, as Virginia Woolf put it, a “disembodied trance-like intense rapture”. Education — learning to analyse literature — breaks that spell. By the time we reach adulthood, Patterson suggests, reading has become “mostly an interrupted process, with different degrees of attention”.

Our desire to reclaim the rapt attention of childhood can, perhaps, account for the popularity of genre fiction: easy to digest and formulaic in nature, it suits a distracted adult appetite.

Patterson’s view of such books is resolutely unsnobbish: he discusses romance and detective stories alongside “great literature” with respect and appreciation. In a moving section about the writing of Jilly Cooper, Patterson recounts how the soothing predictability of her books brought him solace as his first wife, Jenny Diski, was dying of cancer.

Not all the books in his library receive such a generous assessment. For him, “literary fiction” that is “readable” rather than stylistically or intellectually interesting is a particular source of chagrin. Ian McEwan is given a damning review. His novels are described as “passé” and “increasingly wooden” — “essays pinned onto a fictional character’s thought”.

This criticism (which recalls those sometimes levelled at Sally Rooney, another darling of “literary” publishing) is rather harsh. It obscures the sheer inventiveness of McEwan’s plots and characters; what’s more, if the simple predictability of romance novels is reason to commend them, why should readability be a problem in McEwan’s case? Nevertheless, opposing some of Patterson’s opinions is the point: if reading is about thinking independently, then we should expect to disagree.

The beauty of books is that, once out in the world, they are fair game for interpretation and adaptation, for praise and censure. The delightful epigraph to Patterson’s book is George Crabbe’s poem “The Library”, which concludes that books don’t “tell to various people various things,/ But show to subjects, what they show to kings”.

Patterson’s book is a wonderful demonstration of this principle: he admires Cooper’s Rivals even though it might be deemed too “lowbrow” for him, an esteemed Cambridge don. Likewise, less eminent readers than Patterson are free to admire those writers he doesn’t rate as highly.

Creating a library is, like reading itself, always a personal endeavour. Patterson’s readers are likely to be book-lovers anyway, but his message is one worth emphasising to everyone: the most precious library is that which, through reading, we can build within our minds.