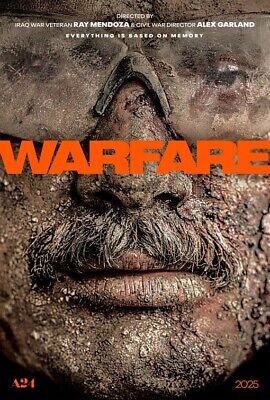

Warfare (2025) ★★★★★

A year after the release of Civil War, one of the best films of 2024, Alex Garland returns with more fighting. The last film was set in a fictional near-future America. This one, Warfare, is a true story from the near past of Iraq.

It’s based on the worst hour of the life of the film’s co-writer and co-director, Ray Mendoza, a US Navy SEAL in Iraq. On a routine mission in 2006, his unit came under attack, leaving them sheltering in a house surrounded by insurgents, with one of their local interpreters killed and two of their unit very seriously wounded.

Just 90 minutes long, the film slowly builds tension as the soldiers realise what is coming, then becomes utterly gripping once the shooting starts. It feels as close a depiction of modern combat as we’ve seen on screen: the bleeding wounds, the screaming and the confusion all press down on us. It will not be to everyone’s taste.

It is a pure distillation of the theory that character is revealed by action

The enemy, though they’re constantly firing at the building, are seen only fleetingly. Last year, talking about Zulu, I speculated that a modern film about such an incident would tell us the stories of both sides, rather than simply treating one of them as a faceless horde. As it turns out, this isn’t the case. Here we learn nothing about the insurgents except that there are lots of them, and they’re coming to kill the SEALs.

But then we learn very little about the SEALs. Almost all the film is in real time: we get no backgrounds to any of the characters, nor any idea of what they were supposed to be doing before their mission went wrong. Their names and roles remain mysterious. It is a pure distillation of the theory that character is revealed by action.

Perhaps an intimate portrait of combat like this one is bound to feel one-sided. One of the great scenes of Civil War sees journalists asking a soldier to explain what he’s doing. He looks at them like they’re idiots: someone is trying to kill him, he explains, so he is trying to kill that person first.

Warfare rejects the usual tropes of its genre: there is no tough sergeant or young soldier doomed in our minds the moment he reveals his wife is pregnant. There are few heroics and no feats of marksmanship: both sides blast away in the general direction of the other while trying not to get hit themselves.

The film came about because Mendoza was the military adviser on Civil War and told Garland about his experiences in Iraq. Having secured the cooperation of his colleagues in recreating the battle, they say that it is as close as they can get to what happened. But if the perspective is that of US soldiers, the film is hardly flattering to them: we see them sending Iraqi soldiers into danger first; the elite unit falls apart after the attack; US commanders come across poorly.

More than all of that, the question you’re left with is how on earth, once the occupation of Iraq had reached this stage, the US ever thought it could succeed. Every so often we get a glimpse of the Iraqis whose house the soldiers have taken over. Whatever their views might have been before these events, it seems unlikely they supported the US presence after their home was destroyed.

One more thing is striking: despite Garland’s insistence that the usual filmic gimmicks were rejected, he and Mendoza have still produced a film with a perfect three-act narrative arc, from the identification of the quest (getting out alive), through the failure of the initial plan to the final resolution. Is this simply how humans remember things? Is this the form that a movie naturally falls into in the edit suite? Perhaps it’s just that such stories are the ones that one man tells another, who replies: “That would make a hell of a movie.”