This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

What is there left to be said about The Beatles? The most successful pop band the world has ever seen has generated an incalculable level of coverage since their first single “Love Me Do” was released in 1962.

It is not only their music which is ubiquitous, but also their influence. There seems to be a Beatles song for every event whether it is a funeral, christening, F.A. Cup final or jubilee. Our fascination shows little sign of fading: their latest Number 1 single, “Now and Then”, reached the top of the charts 60 years after their first.

It is perhaps because of this astonishing level of success that we have long since lost any real perspective on The Beatles. Ever since John Lennon claimed that the band was bigger than Jesus in 1966, they seem to have attracted only extreme responses.

On the one side, you have those who travel to Strawberry Field, Penny Lane and Abbey Road to scratch peace signs and hearts into road signs; at the other extreme, there is Michael Abram, who stabbed George Harrison 40 times, and Mark Chapman, who assassinated Lennon in 1980.

With a few notable exceptions, critics and publishers are not exempt from this polarised position, both in their claims and their language. (American writer Adam Gopnik has claimed that “Penny Lane” is the greatest work of art of the 20th century.)

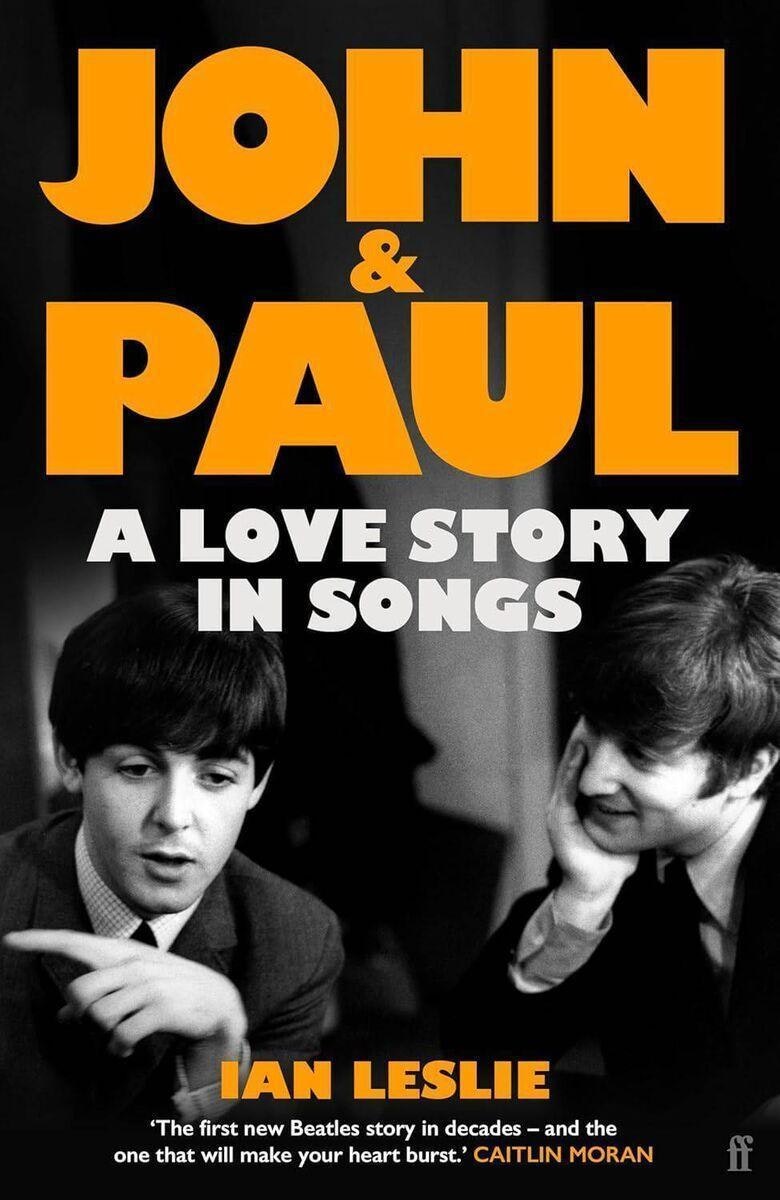

The latest contribution to the genre of Beatles studies is Ian Leslie’s John and Paul: A Love Story in Songs. The title tells us a lot: Leslie focuses on the band’s two main songwriters through the songs that helped shape their relationship.

The homoerotic connotation of the subtitle is deliberate, as Leslie goes on to claim that, in all but act, these two men were artistic, emotional and intellectual lovers. Lennon’s heterosexuality has been questioned by other authors, but it is not difficult to imagine what the most sardonic Beatle would have said about this angle.

The book works so well largely due to Leslie’s often brilliant analysis of songs that have been deadened through overexposure. His insights are not only original and interesting but are rooted in a secure, well-researched understanding of musical composition. Leslie is a fan, and although this book had as its source a Substack called “64 Reasons to Love Paul McCartney”, it avoids being a hagiography: he is honest about the many flaws of both men.

That said, Leslie is not immune from making overblown claims. He writes that they did not just form a band but “invented their own future, and, in doing so, our present”. To do this, they “merged their souls”. When Lennon and McCartney first met, “the twentieth century tilted on its axis”. All of this is, of course, specious. But they did create some of the finest pop songs ever written, often at astonishing speed (“Rubber Soul” was recorded in two weeks).

It is not easy writing about music, rendering something outside language in a medium that constrains or misrepresents its innate appeal. But Leslie is very good at creating an image that perfectly captures a song: “Penny Lane” is a “diorama”; “Strawberry Fields Forever” is a “smudged and faded print of happiness”.

It is in his analysis of song mechanics that Leslie really excels. He focuses on the “melting transition from major IV to minor IV” that Lennon used so effectively in “If I Fell”, “In My Life” and “Nowhere Man”. In “Tomorrow Never Knows”, Lennon uses a line of iambic pentameter, followed by an answering phrase based on a gerund … a structure that answers and inverts the pattern of “Yesterday”. This detail — granular and almost obsessive — fills many pages, but is genuinely educational and never overlong.

By exploring these patterns, and the craft behind the art, Leslie builds a picture of a complicated, artistically fraught but astonishingly inventive relationship that often worked at a subconscious level. The irony is that although they produced some of the most joyous, celebrated music of the 20th century, it was — especially with Lennon — shot through with sadness and self-doubt. That emotional chiaroscuro coloured everything they did, adding a hidden complexity to even their most throwaway songs.

Leslie opens by stating that we need a new story about The Beatles. Initially I demurred, but my misgivings were misplaced. This book brings a new level of analysis and insight to a subject that seemed sucked dry of new insights. But really all Lennon and McCartney needed was the right author to make us see the familiar anew. The Beatles now have the (paperback) writer they deserve.