This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

In Our Time is a jewel, admired by all. The wide-ranging discussion on Radio 4 fulfils all three parts of the BBC’s founding purpose: it informs, entertains and educates. Each week two million listeners tune in and say, “I learned something interesting today.”

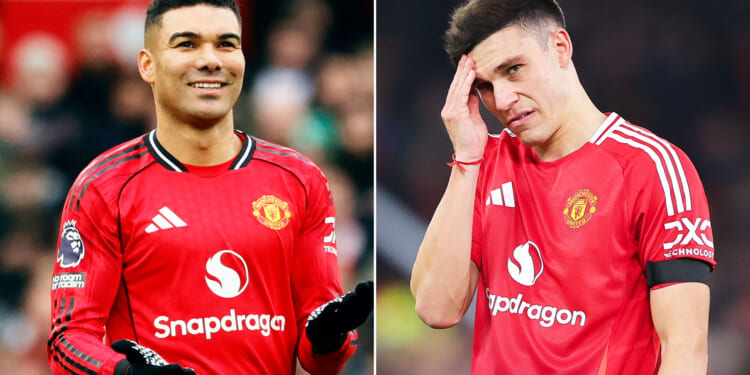

It will carry on, every Thursday at 9am, but shorn of the host. Melvyn Bragg has declared his innings closed after 27 years, and 1,038 programmes. In all he has spent 64 years as a broadcaster. Now, at 86, he’s losing his voice. Yes, 64 years! The Beatles were still dodging bottles in Hamburg, and the first James Bond film was 12 months away, when the young pup, fresh from Oxford, joined the BBC as a trainee. So he’s seen it all.

Brought up above a pub in Wigton, near Carlisle, he was liberated by sympathetic teachers at the town’s grammar school. Then it was off to Wadham College, to read modern history. There was no such thing as media studies in those days, and the world was a happier place for it.

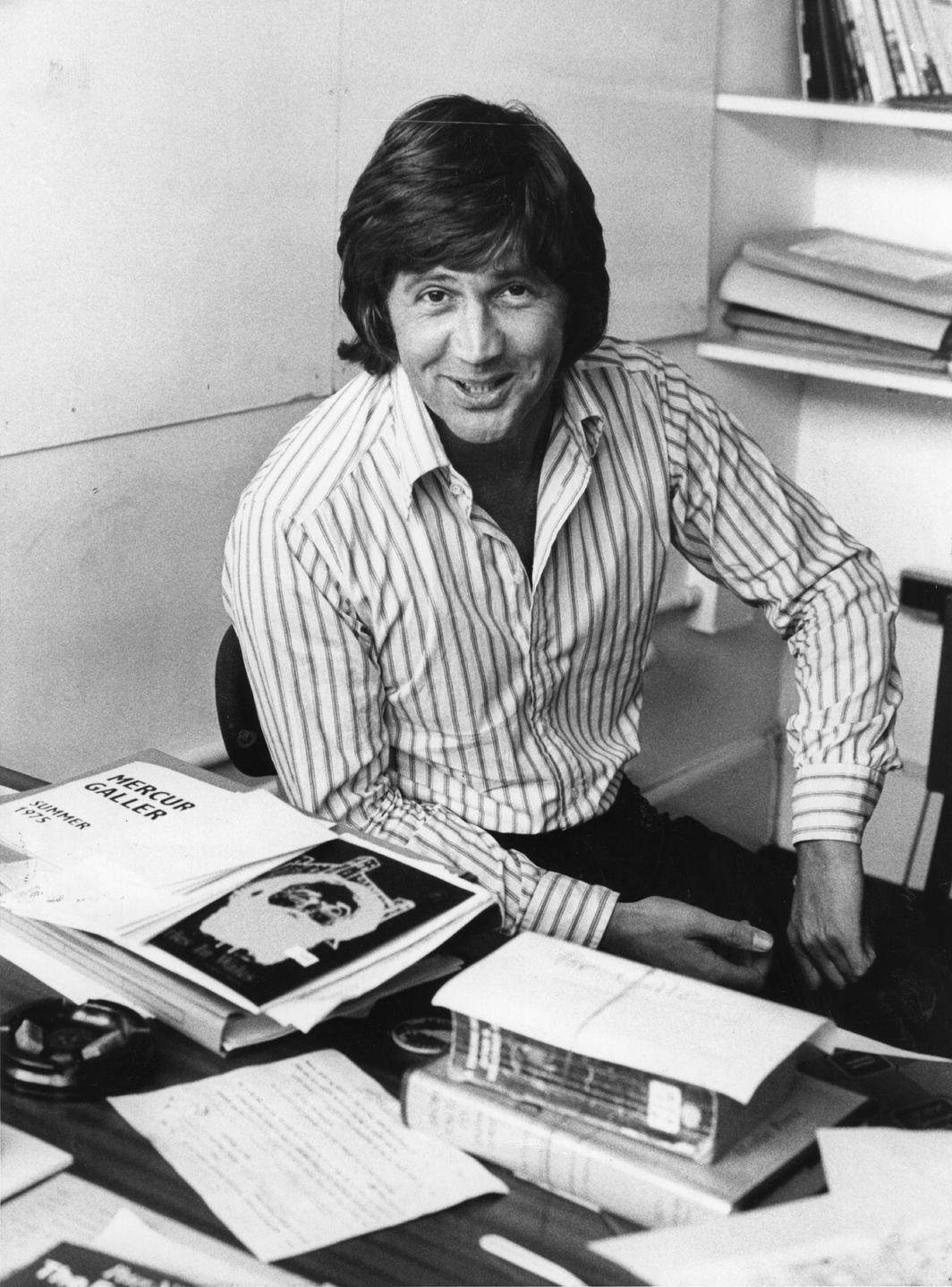

He began in radio, and was soon stroking an oar on Huw Wheldon’s galleon at Monitor, the television programme devoted to the performing arts. Ken Russell had just made his famous portrait of Elgar, which helped revise opinions of the composer. It was a good place for an ambitious young man to be.

Although he longed to be a novelist, and eventually wrote the books to prove it, Bragg stepped confidently into his new world. In time he became the presenter of a TV books programme, Read All About It, before helming The Lively Arts.

In 1978 London Weekend Television recruited him to present The South Bank Show, which ran until 2010. It ran out of puff towards the end, as executives demanded easy profiles to run alongside weightier subjects. But he could point to interviews with Harold Pinter, Arthur Miller and William Golding, as well as the last sighting of Dennis Potter.

As the host of Start The Week on Monday mornings, Bragg retained a BBC presence. When he became a Labour peer in 1998 he lost that slot. It was a disappointment, yet it led to his return as the man who has made In Our Time such a thumping triumph.

It’s easy to despair of low standards. Mastermind, supposedly an intellectual challenge, now features low-wattage “specialist” questions that would have been unacceptable 20 years ago. Many students on University Challenge appear to know nothing about the treasure trove of Western literature and music.

There is no longer a television show devoted to books. If you caught the abysmal programme fronted by Sarah Cox, a teenager entering her sixth decade, you might think that was a consummation devoutly to be wished. Why run a show like that unless you enjoy reading?

Yet two million people each week swim against this tide of dimness, to hear experts shine a light on subjects like Julian of Norwich, dragons, copyright, Paul von Hindenburg and the poetry of Sir Thomas Wyatt. Those were five topics covered in Bragg’s farewell season.

At heart he remains the Cumbrian lad whose curiosity was prodded by those kindly schoolmasters. That childhood was a formidable quarry for his novels, 22 in all, and there have been plenty of other books. A vivid memoir of youth, Back in the Day, is well worth a read.

Would a young man like Bragg get on today? One or two must, though producers do not always look in the right direction. The talk is of diversity and inclusivity, which sounds fine and dandy, but doesn’t necessarily bring to the fore those independent souls who might make a difference.

Good programmes are unlikely to emerge from groupthink. They are shaped by men and women who trust their instincts, and act upon them. In Our Time was created by Olivia Seligman. The producing duties are now shared by Simon Tillotson and Victoria Brignell. Well done, those three.

Philip Larkin, in “Church Going”, wrote that “someone will forever be surprising a hunger in himself to be more serious”. The lines are often quoted, and in Bragg’s case, there is just cause. For nearly three decades he has invited listeners to forget the frivolity of a world that cares little for hard thinking.

He’s had a grand life, though amidst the public acclaim there has been private tragedy. For someone who has achieved so much he cuts a withdrawn figure, as though he is still expecting, after all these years, to be found out.

The talk is now of his successor, and the usual hats have been flung into the arena. The programme is associated so closely with its original voice that whoever claims the hat will be regarded with suspicion. Listeners tend to feel very proprietorial about these things.

What is the lesson of this heartwarming tale? There are more intelligent folk out there than is sometimes supposed, and they like their minds to be stretched. Bragg’s successor has mighty boots to fill.