On the morning of May 20, 1979, a young student named Graham Smith received an urgent message to telephone his father.

‘I knew there was something wrong because he wouldn’t call like that normally,’ he reflects.

And something was indeed terribly wrong. When Graham reached his father, ex-policeman Ron, he was told the shocking news that his beloved older sister Helen had been found dead in the grounds of an apartment block in Saudi Arabia, where the 23-year-old had been working as a nurse.

‘My mother and father’s initial thoughts were that she had jumped,’ the now 68-year-old says. ‘They thought she had committed suicide. It was terrible.’

A further horrific update was to follow: it took 24 hours for the devastated Smith family to be told that another body, that of Dutch boat captain Johannes Otten, had been found alongside Helen’s, a revelation which surely suggested a different, more sinister explanation for the young nurse’s death.

Yet as they digested this information, it was already crystal clear that the authorities in Saudi were keen to rule the tragic double deaths an accident.

Backed up by diplomats from the British Foreign Office, the Saudi police declared that the couple had fallen to their deaths while making love on the balcony of a flat where they had been attending an illicit drinking party.

This alone was enough to generate lurid headlines around the world. But Ron never believed them. Until his own death in 2011 at the age of 83, he remained convinced his daughter’s death was the result of foul play and had been wilfully covered up by authorities, both here and in Saudi Arabia, to preserve the fragile but vital relationship between the UK and the oil-rich country.

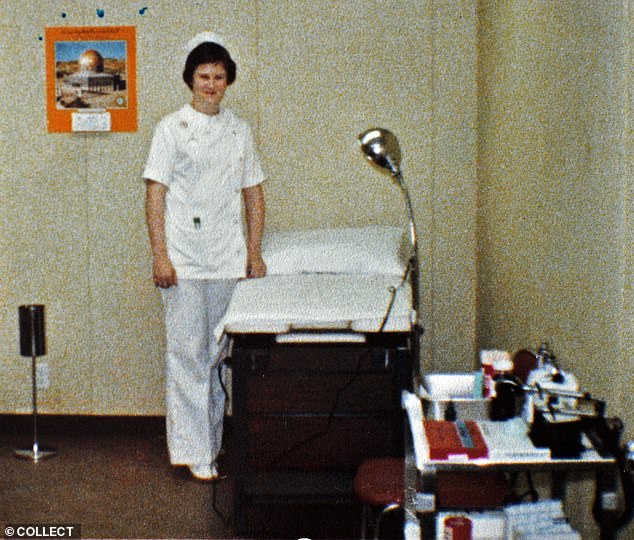

Helen Smith had been working as a nurse in Saudi Arabia when she died

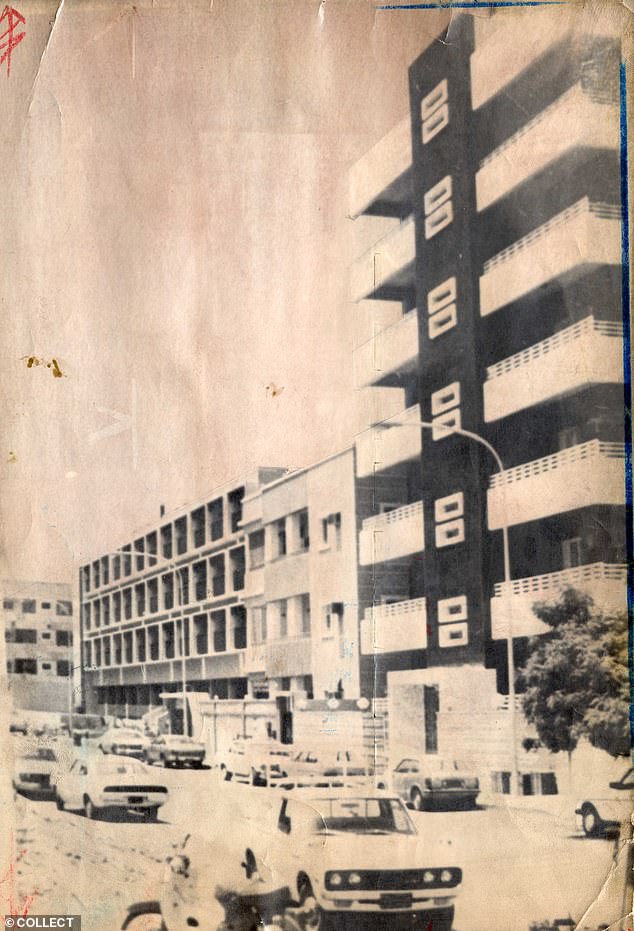

Helen’s body was found in the grounds of an apartment block in Jeddah

Now, nearly half a century on, a new Channel 4 documentary reveals that Ron was right all along. Using the Freedom of Information Act to access thousands of previously unseen classified documents, it reveals that diplomats and senior public officials here in the UK, among them the then Director of Public Prosecutions, also voiced a strong suspicion that both Helen and Johannes were murdered.

Death In The Desert: The Nurse Helen Mystery also reveals how the death was discussed at senior government minister level, including by the then inaugural Minister for Europe, Douglas Hurd.

‘The true story of Helen’s death was a devastatingly inconvenient truth for authorities at the time,’ says solicitor Ruth Bundey, who now 77, supported Ron in his long quest for justice for his daughter, and appears in the documentary.

‘Ron always believed it was a cover-up, and we can see now beyond any doubt that that was the case,’ she tells me. ‘He was frequently described as being an obsessive in his search for the truth, but now documents have revealed that many people in senior positions shared his suspicions. While we may never know the actual truth, if we had been in possession of these documents from the start, there could have been a totally different outcome at the inquest into Helen’s death.’

That she would never come back never crossed Helen’s mind when she left these shores to take up a nursing post in Saudi Arabia in 1978. The eldest of four children born to Ron and his wife Jeryl (the couple later divorced), she was one of many Brits drawn to the country in the wake of its booming oil industry. In the documentary, her brother Graham remembers accompanying his sociable, caring sister to the airport for her flight to the Saudi city of Jeddah.

‘We were close, so much so that [on the] last night, before she flew to Saudi Arabia, I went and spent the night with her, and then saw her off at Heathrow,’ he recalls. ‘That was the last time I ever saw her.’

Letters home suggested Helen was discovering a passion for deep-sea diving and having a whale of a time but, while it was undoubtedly fun to be young and British in Jeddah in the late 1970s, strict laws meant partying had to happen behind closed doors.

Helen’s brother and father, Graham and Ron Smith, arrive with solicitor Ruth Bundey at the inquest of her death at Leeds’s Town Hall in 1982

In the documentary, Graham, now 68, remembers accompanying his sociable, caring sister to the airport for her flight to Jeddah

Ruth, now 77, supported Ron in his long quest for justice for his daughter

As a result, expats brewed alcohol in their baths to be served at secret parties. It was just such a party that Helen attended on the night of her death, at the home of British hospital doctor Richard Arnot and his wife Penny, for whom she sometimes babysat.

Helen and Penny were the only two women present.

The exact events of that night remain shrouded in mystery, although some guests subsequently claimed they had seen Helen and Johannes – whose body was returned to Holland and buried without a post-mortem examination – disappear on to the balcony and presumed they were having sex.

Either way, early the next morning Helen’s body, clothed but with her underwear partly off, was discovered on the ground by a local resident. Johannes, whose underpants were around his thighs, was impaled nearby on the spiked railings surrounding the apartment block.

The fact that it took 24 hours for the Smith family to learn of Johannes’ death alongside Helen left their father livid, recalls Graham. And by then – already – a version of events was in the process of being set down by the Saudi authorities and the British Foreign Office: that the couple had fallen to their deaths from the balcony while having sex.

It was a version the Foreign Office was only too keen to accept at what was a crucial time in Anglo-Saudi relations: in February, Queen Elizabeth II had visited Saudi Arabia for the first time. And within days of the May General Election, new Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher entertained Riyadh’s governor at No 10.

Yet, as Ruth recalls, from the outset Ron – who immediately flew to Saudi Arabia to examine Helen’s body – refused to accept the official explanation.

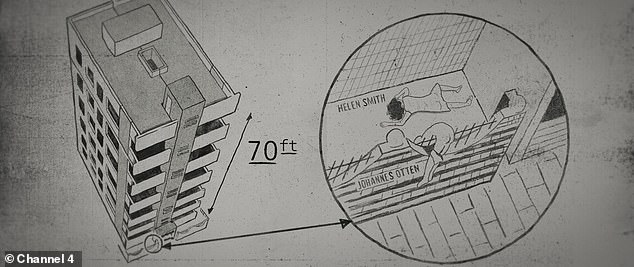

Along with a nurse at the time, he pointed out that his daughter’s injuries were completely inconsistent with a fall on to a marble floor from 70 ft – there was little blood, and no bone fractures. One arm was also at an angle above her head in a state of rigor mortis, an elevation that would have been impossible if she had fallen while still alive.

‘Ron and the rest of us in his legal team always felt that Helen had been subjected to some terrible and unlawful violence, possibly as a result of jealousy and or drunkenness among the men at the party,’ Ruth Bundey puts it now. ‘We were of the view that Helen had been set upon at some point for whatever motive, and then taken down and placed on the ground outside the flats to give the impression that she had fallen.’

Only now, courtesy of those previously unseen documents featured in the documentary, does she know that many senior diplomats felt the same.

‘I believe that the body does not bear injuries consistent with a fall of 70 ft,’ one diplomat wrote from Jeddah to London within days of Helen’s death, adding: ‘I don’t think the case will be solved so easily.’ Within two days of the death, another diplomat refers to it in terms of a whodunit.

‘It is possible that a third party murdered the couple, a boyfriend filled with drink, jealousy, or both, may have discovered a naked couple and heaved them over the balcony,’ he wrote, adding his fears that, should the Jeddah police investigate further, they may come up with some ‘rather nasty answers’.

Helen attended a party on the night of her death at the home of British hospital doctor Richard Arnot and his wife Penny, for whom she sometimes babysat

‘The true story of Helen’s death was a devastatingly inconvenient truth for authorities at the time,’ says Ruth

None of this was good news for the British authorities, who were also battling the diplomatically nightmarish spectacle of the party’s host Penny Arnot – who along with her husband was jailed for alcohol offences after the party – facing a public flogging for not only hosting an illicit do but for adultery, after it emerged that Penny had had sex with another man that evening.

In fact, the Saudi authorities spared her from her flogging and 14 months after Helen’s death, the Arnots were able to leave the country. Nonetheless, ‘a tragic accident and a young girl falling from a balcony was a tidy way to try to deal with one aspect of this at least’, Ruth says.

But the authorities had not reckoned with Ron. Despite the lack of co-operation on the part of the Saudis to further investigate Helen’s death, he determined to bring his daughter back to the UK where, he hoped, a post-mortem examination and an inquest could take place.

‘As an ex-copper, he knew about investigation, and he knew about not leaving any stone unturned,’ Ruth says. Finally, in June 1980, 13 months after her death, a British Airways Flight brought Helen Smith’s body home from Jeddah. Ron now faced further obstacles: British nationals who died overseas were not entitled to an inquest in their home country whatever the circumstances – so, with Ruth’s help, he had to take his fight to the courts.

When his request for an inquest in Leeds, the nearest city to Helen’s birthplace, was turned down, Ron successfully fought the decision in the Divisional Court and then the Court of Appeal, establishing an important principle that remains to this day. ‘In that sense, Ron left an incredibly powerful legacy,’ says Ruth.

‘His work changed the law so that, ever since Helen’s death, families in England and Wales have recourse to proper investigations when British nationals die in difficult circumstances overseas and are entitled to a coroner’s inquest here in the UK.’

The new documentary analyses the events of 1979 – including how the bodies were found

That decision meant that, on coroner’s orders, an investigation could now be undertaken by the British police. All the while, government officials held the party line: Helen’s death was an accident. This was what Douglas Hurd – who is now 95 – firmly told Ron in a meeting which took place before the inquest.

Yet, as the documentary shows, behind the scenes it was a different story: Hurd was all too aware of a letter from the Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Thomas Hetherington, to West Yorkshire police telling them there ‘is strong suspicion that both persons were murdered’.

‘One can imagine further purely legal action as a result of the findings of the Director of Public Prosecutions under the Offences Against The Person Act,’ he wrote to officials. One missive from a Foreign Office employee, referencing this ‘strong suspicion’, has a scribbled handwritten note at the bottom. ‘Potential dynamite’! it reads. Yet Ron and his legal team – including the now renowned lawyer Geoffrey Robertson KC and Graham’s barrister Sir Stephen Sedley – remained oblivious.

‘We were raising inconsistencies, and here we now see those higher up had the same doubts as him, but never shared them,’ says Ruth. ‘It was unfair on Ron because he was always presented as somebody completely obsessed to the point of being irrational.’

Even the inquest was a troublesome affair. While it heard evidence that Helen could have been beaten and raped before her death – and that the Home Office pathologist who had examined her had omitted injuries consistent with rape from his report – the newly uncovered documents also show that the coroner was sharing more information with the Foreign Office than was appropriate.

‘It’s really quite shocking,’ Geoffrey Robertson says in the documentary. ‘Coroner’s inquiries should be independent of government, but these newly released documents show the coroner briefing the Foreign Office on the police investigation, and the Foreign Office in turn asking if announcements on the case might clash with Saudi state visits.’

Crucially, however, despite being directed to return a verdict of accidental death, the jury returned an open verdict.

‘Ron was very relieved,’ Ruth recalls. ‘It was the jury saying that they rejected the idea of an accident but had not been presented with sufficient evidence to reach a specific different verdict. Leaving it open also meant that Ron was always hopeful, as was I, that somebody would eventually come forward and tell the truth.’

I really do now appreciate what my father did. He most certainly did right by my sister. He was truly a champion.

It was the reason that, at her father’s insistence, Helen’s body remained more than 30 years in storage at Leeds General Infirmary. ‘Many people thought that was outrageous, but it was Ron’s efforts to ensure that, if something did come up which was new, it could be double checked with a further physical examination,’ Ruth says.

Finally, in 2009, Ron acquiesced to his ex-wife’s fervent wish that her daughter’s body be laid to rest, and Helen was cremated, her ashes scattered on the edge of Ilkley Moor, West Yorkshire, where she had loved to play as a child.

Ron died two years later, never having shaken his belief that the truth about the exact circumstances of his daughter’s death might emerge.

‘Both of us never shut our minds to that,’ Ruth says now. ‘I still live in hope that somebody will have an attack of conscience. People can hide things for years, and then there comes a point in their lives when they think perhaps it’s time they said what actually happened.’

For Graham, meanwhile, uncovering the vast trove of previously unseen documents has instilled a new-found respect for the sometimes difficult man with whom he often clashed.

‘I really do now appreciate what my father did,’ he says. ‘He most certainly did right by my sister. He was truly a champion.’

A champion of the sister whose loss he still mourns.

‘I do miss her,’ he says. ‘Even after all these years.’

Death In The Desert: The Nurse Helen Mystery is on Channel 4 at 9pm on Monday.